“Racial and ethnic inequities in the US health care system have been unremitting since the beginning of the country. In the 19th and 20th centuries, segregated black hospitals were emblematic of separate but unequal health care,” begins the editorial introducing an entire issue of JAMA dedicated to racial and ethnic disparities and inequities in medicine and health care, published August 17, 2021.

This is not your typical edition of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The coronavirus pandemic has changed so many aspects of American health care for so many people, including doctors.

Since the second quarter of 2020, I’ve noticed that JAMA has devoted increasing column inches to the issues of health equity, social determinants of health, and structural racism in U.S. health care.

Since the second quarter of 2020, I’ve noticed that JAMA has devoted increasing column inches to the issues of health equity, social determinants of health, and structural racism in U.S. health care.

In that introductory editorial, Ending Structural Racism in the US Health Care System to Eliminate Health Care Inequities, Ortega and Roby write that,

“3 studies in this issue of JAMA show that access to and utilization of services is not merely predicated on health insurance or the availability of health care. As an important example, the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that, for instance, despite widespread availability of free vaccines, there are continued inequities in vaccine coverage, which perpetuates COVID-19–related health inequities. The elimination of health care inequities will require effective integration of health care systems with communities and the social safety net. Moreover, health equity can only be achieved through attention to the needs and perceptions of the communities served and to the elimination of racism and biases deeply imbedded in the system.”

To solve the challenge of structural racism in American health care, the authors say, “there needs to be much more intensified and multifaceted approaches that by necessity will require a much larger and committed investment in research, training, clinic practice, and community engagement.”

Thus begins what should be must-read content for every person working in any aspect of health care in America. In this post, I’ll share just a handful of insights that were particularly impactful to my work and my commitment to work toward health citizenship for all people in the U.S.

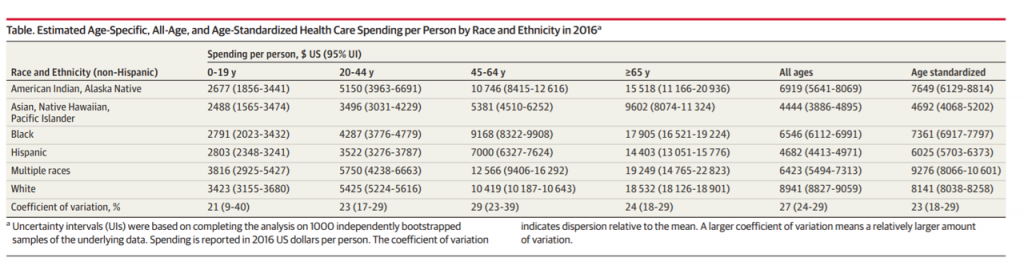

First, consider the big health economics picture painted in the paper US Health Care Spending by Race and Ethnicity. The table arrays data the researchers analyzed from 2002 to 2016, identifying patterns of six types of medical services used by race and age group.

We can see that health care spending varied by race and ethnicity after adjusting for age and medical conditions. Spending per person for Black and American Indian and Alaska Native people was significantly lower than for other racial/ethnic groups. Black and AI/AN people also have lower life expectancies.

We can see that health care spending varied by race and ethnicity after adjusting for age and medical conditions. Spending per person for Black and American Indian and Alaska Native people was significantly lower than for other racial/ethnic groups. Black and AI/AN people also have lower life expectancies.

The authors suggest that investing more in prevention and health promotion for these groups could improve health outcomes and get to more equitable spending levels. For Black patients, lower utilization of ambulatory care and higher use of inpatient, emergency department, and nursing suggest greater spender downstream that might be prevented by more spending upstream on primary care, prevention, and early detection of disease.

They conclude, “the US is consistently the wealthiest country in the world with subpar levels of coverage for a core set of health services; these findings provide additional evidence of the need to reduce disparities.”

Next, let’s visit the article looking at Trends in Differences in Health Status and Health Care Access and Affordability by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S. The authors analyzed 20 years’ worth of data on outcomes by racial and ethnic differences and find that health status, access, and affordability largely persisted among people of racial and ethnic minorities over two decades.

Next, let’s visit the article looking at Trends in Differences in Health Status and Health Care Access and Affordability by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S. The authors analyzed 20 years’ worth of data on outcomes by racial and ethnic differences and find that health status, access, and affordability largely persisted among people of racial and ethnic minorities over two decades.

The over-arching finding in this study was for health status, with significant differences between Black and White patients persisting over time, the authors concluded.

Black, Latino/Hispanic, and American Indian people have worse self-reported health. This study showed no decrease in these patients’ ratings of poor or fair health.

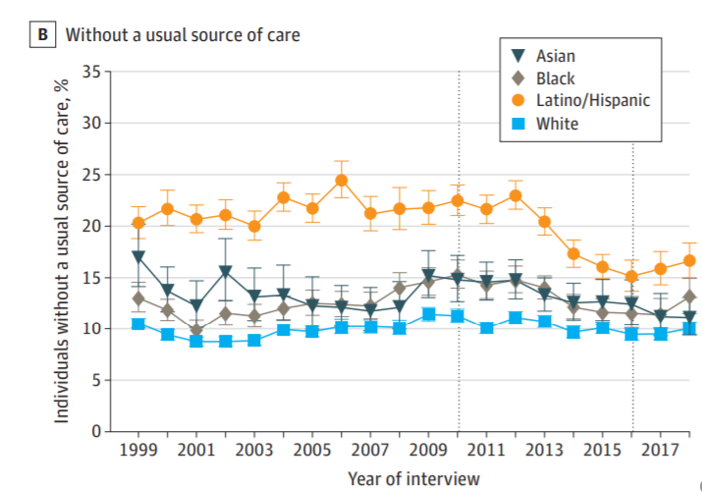

This chart from the study illustrates one aspect of self-reported care: people without a usual source of medical care. Here, we see that Latino/Hispanic and Black people were more likely to lack an ongoing relationship with a physician or primary care clinic.

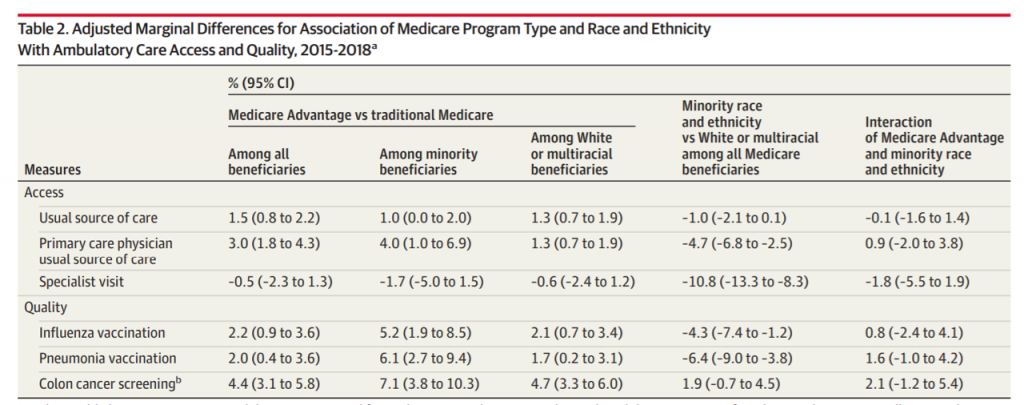

Finally, check out Association of Race and Ethnicity and Medicare Program Type With Ambulatory Care Access and Quality Measures. This research looked at enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans compared with traditional Medicare. The study found that across all Medicare Advantage enrollees, members had better outcomes for access and quality. However, Black Medicare Advantage members were more likely to experience worse outcomes for access and quality than White beneficiaries.

Finally, check out Association of Race and Ethnicity and Medicare Program Type With Ambulatory Care Access and Quality Measures. This research looked at enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans compared with traditional Medicare. The study found that across all Medicare Advantage enrollees, members had better outcomes for access and quality. However, Black Medicare Advantage members were more likely to experience worse outcomes for access and quality than White beneficiaries.

Access metrics included usual source of care (noted in the previous study’s chart, above), having a primary care physician as a usual source of care, and having a visit to a specialist. Quality metrics quantified flu vaccination, pneumonia vaccination, and screening for colon cancer (i.e., colonoscopy).

Do check out the additional content in this special JAMA issue, with essays on addressing anti-black racism in health care (with steps for non-black health care professionals to take), race and the patient-physician relationship in 2021, and one of my favorite topic-opportunities, partnering with faith-based communities to address health disparities (in this case, COVID-19 vaccination rates among Black and Latino people).

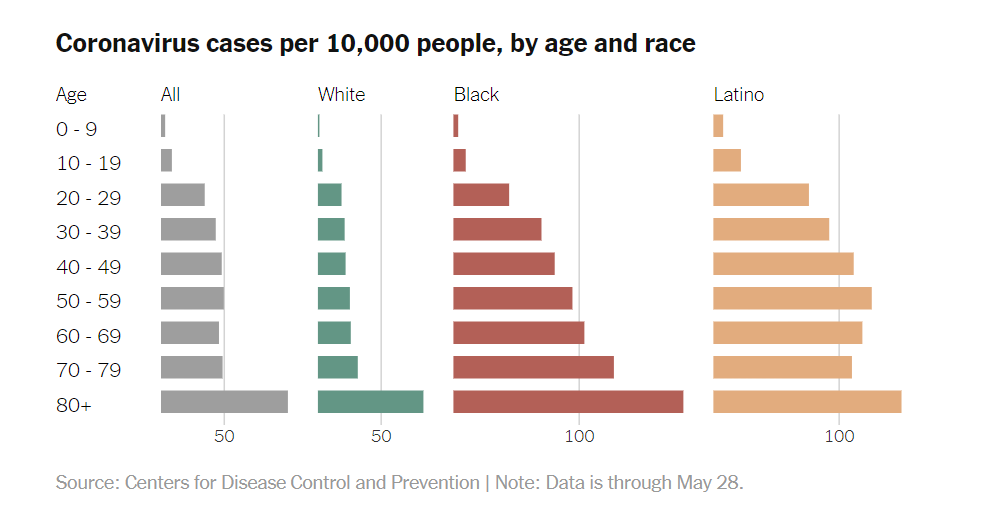

Health Populi’s Hot Points: By June 2020, it became clear to the Centers for Disease Control that COVID-19 had been exacting a tougher toll on the lives of people of color in the U.S. than on white people.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: By June 2020, it became clear to the Centers for Disease Control that COVID-19 had been exacting a tougher toll on the lives of people of color in the U.S. than on white people.

The bar chart here was drawn on the data the CDC presented in June 2020 getting granular on coronavirus cases by age and race. What’s striking about the shapes of each race/ethnic segment is the further you go right in the chart, the more uniformly long the bars are — for Latinos at the far right, and then for Black Americans illustrated by the brown-red bars.

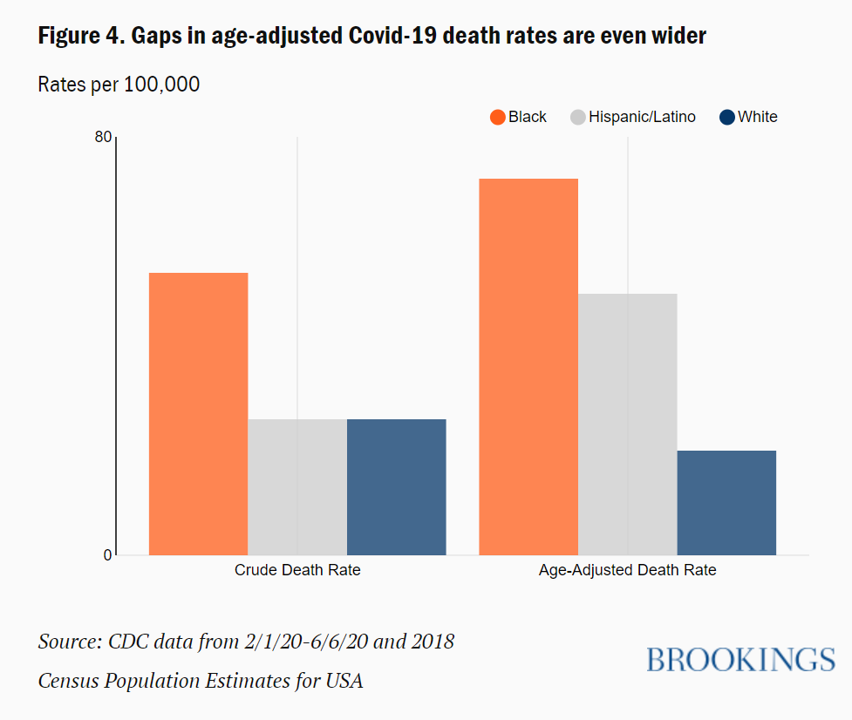

Brookings examined race gaps in COVID-19 deaths based on this CDC data set, finding those gaps were even bigger than they appeared. This orange and blue bar chart clearly portrays Brookings’ observation of the bigger-than-apparent gaps in mortality between black and Hispanic deaths due to COVID-19 compared with those of whites.

Brookings examined race gaps in COVID-19 deaths based on this CDC data set, finding those gaps were even bigger than they appeared. This orange and blue bar chart clearly portrays Brookings’ observation of the bigger-than-apparent gaps in mortality between black and Hispanic deaths due to COVID-19 compared with those of whites.

The pandemic has shone a blindly bright light on health inequities that have persisted in America since the nation’s founding.

As Martin Luther King, Jr., said in 1966, “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhuman.”

Kudos to the editors at JAMA for curating and publishing the August 17th issue addressing many facets and roots of health disparities in the U.S.

As I continue to evolve my own health citizenship, I am reading a book by Minouche Shafik of the London School of Economics called What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract for a Better Society.

Minouche knows that “Caring for others, paying taxes, and benefiting from public services define the social contract that supports and binds us together as a society,” outlining lessons we can learn from countries who have addressed key elements of a better social contract that supports and invests more in each other, but also expects more of us individuals in return.

She starts the chapter on health and health care with the simple sentence, “Being healthy is the most important determinant of our wellbeing.” In getting real about health equity and disparities, the U.S. will have to grapple with just what a fair and equitable social contract could be for all people — our rights as well as our responsibilities to each other.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a