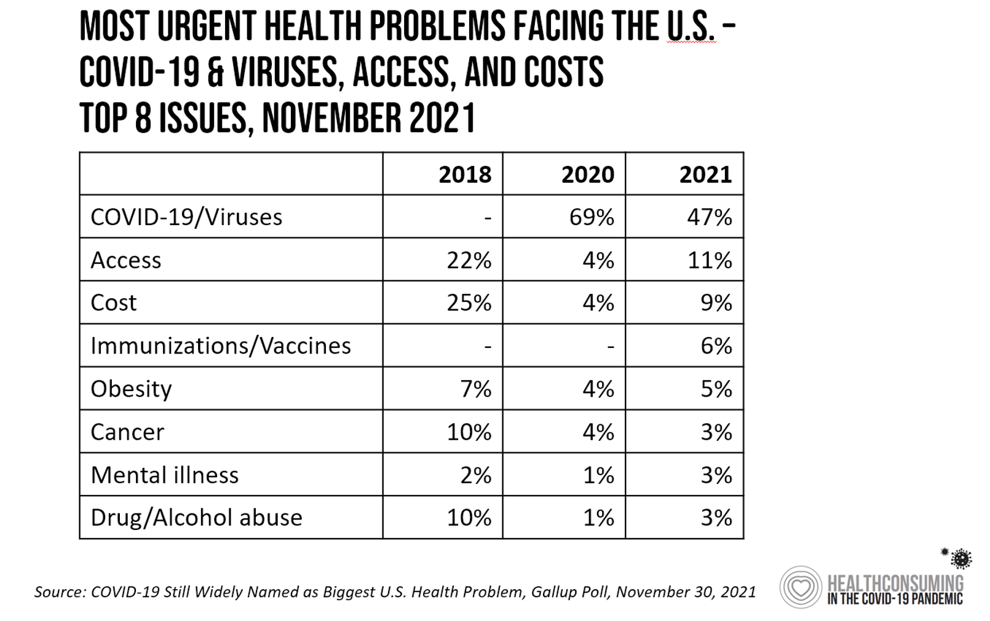

Approaching nearly two years into the pandemic, nearly one-half of Americans cite viruses and COVID-19 as the top health problem facing the U.S.

In a Gallup poll published 30 November, COVID-19 (is) Still Widely Named as Biggest U.S. Health Problem,

In a Gallup poll published 30 November, COVID-19 (is) Still Widely Named as Biggest U.S. Health Problem,

I added the “Is” to Gallup’s press release title because the proportion of people in America citing the coronavirus as the top health care problem facing the nation fell by about one-third — from 69% of health citizens to 47%.

At the same time, the percentage of peopled most concerned about access to health care and costs more than doubled in the year, from 4% to 11% and 9%, respectively.

The importance of these issues, though, far lag behind COVID concerns in terms of top-named health care problem in the U.S., as the first table shows.

Issues such as cancer, mental illness, and drug/alcohol abuse registered quite low in the top 8 problems that people cited

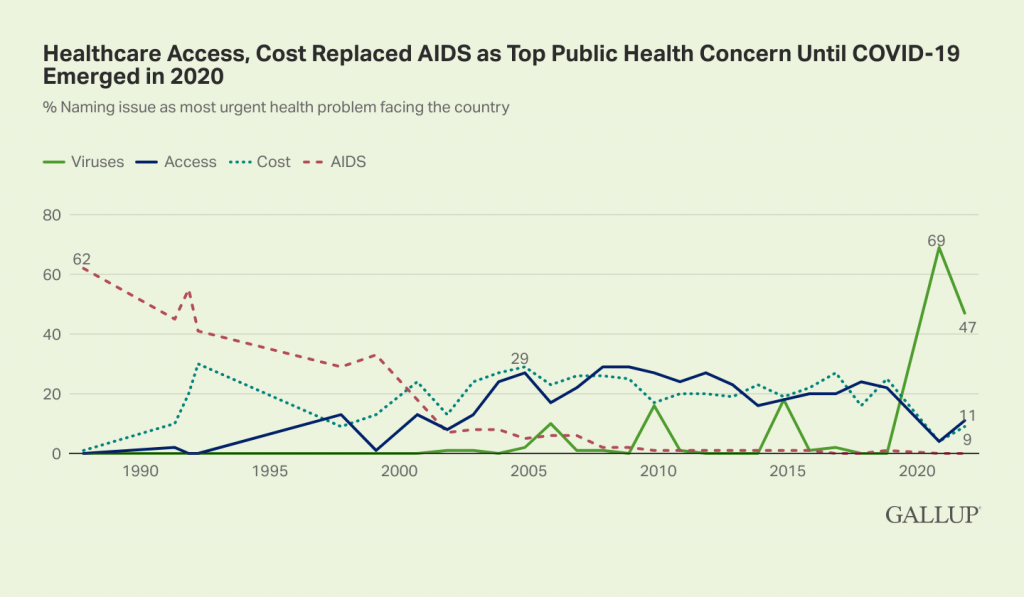

This week marked World AIDS Day on Wednesday 1st December, so it’s timely that Gallup assessed the survey findings in the context of AIDS as a national public health concern since its emergence in the latter 1980s.

This week marked World AIDS Day on Wednesday 1st December, so it’s timely that Gallup assessed the survey findings in the context of AIDS as a national public health concern since its emergence in the latter 1980s.

World AIDS Day was first celebrated in 1988,

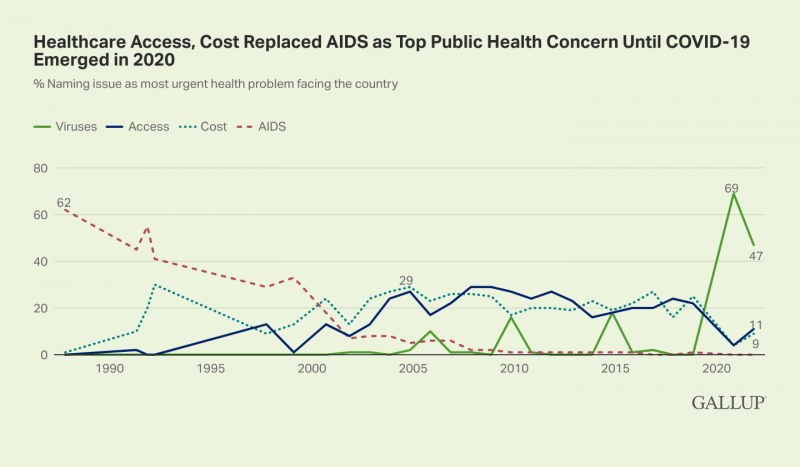

The second (green) chart graphs the timelines for most urgent health problem facing the U.S. since AIDS garnered 62% of Americans’ attention as the #1 health issue. Note that red dotted line declines, then spikes up again in 1991, and once again falls to its lowest level in the late 200s.

“Viruses” (of which HIV is one of many) spiked on the solid green line beyond AIDS’ high watermark at 62%, to 69% in 2020. Then that number fell in the past year, with the advent of vaccines, vaccinations, and health citizens “maturing” in the pandemic era of COVID-19 and learning to live, work, go to school, exercise, and socialize while managing their (self-perceived) risks of exposure to the virus.

Gallup’s bottom-line:

Even before the omicron variant emerged as a potential threat to recent progress in the nation’s recovery from the pandemic, COVID-19 was still Americans’ primary health concern. Only AIDS in the late 1980s and early 1990s received a higher percentage of mentions than COVID-19 does today. Whether concern about the virus plummets further next year or trails off slowly, as concern about AIDS did in the 1990s, may depend on how effective vaccines and medical treatments are at keeping up with new variants and allowing the country, if not the world, to return to its pre-pandemic normal.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: AIDS in America provides some sobering and enlightening context to the COVID-19 pandemic. World AIDS Day in the U.S. in 2021 featured the theme, Ending the HIV Epidemic: Equitable Access, Everyone’s Voice.

This theme bolsters President Biden’s commitment to end HIV globally, especially committed to addressing health inequities and people-centered care.

Health inequities and lack of access have also plagued (no pun intended) efforts to address COVID prevention and treatment in the U.S. Misinformation on vaccinations, treatments, and prevention strategies have gone viral (again, no pun here) via social networks that have empowered certain bad actors and health-detractors to slow vaccinations and the realization of herd immunity in the U.S. and indeed, around the world.

I was alive and just starting my career path in health/economics in the “And the Band Played On” era of AIDS, which took the lives of some dear friends as the Silence=Death project emerged in New York City.

It’s encouraging that scientific evidence and innovation have saved the lives of millions of people vaccinated against the coronavirus. It’s demoralizing that millions of people — albeit a minority, but a sufficient proportion to prevent the mass hospitalizations of Americans occupying inpatient beds throughout the U.S. — still don’t accept the reality that #VaccinesWork.

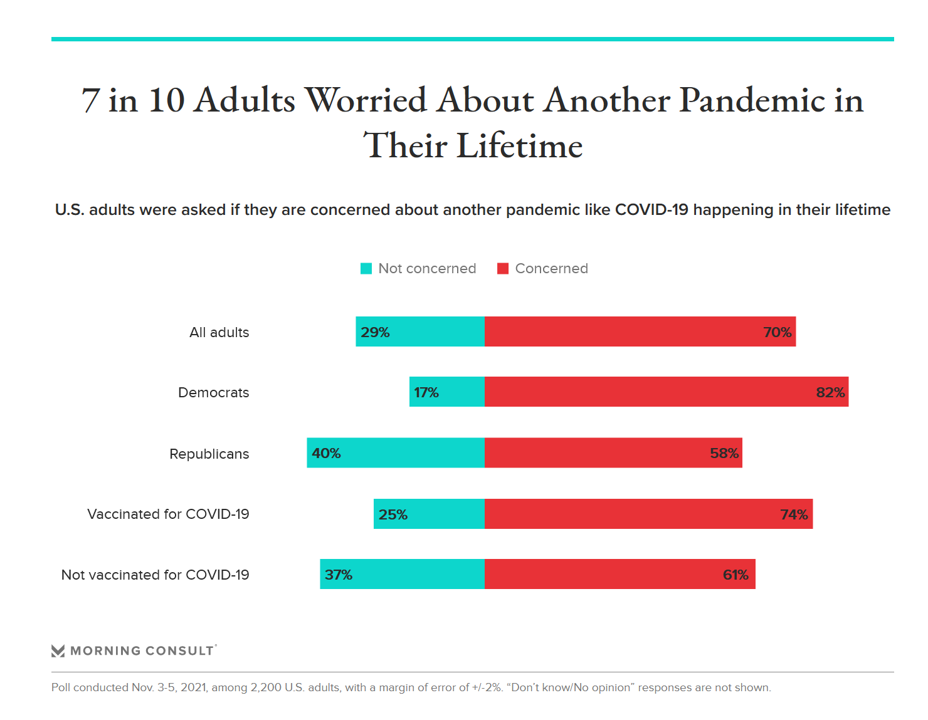

Ironically, the last chart tells the current story (as of early November 2021) about just who is worried about another pandemic in their lifetime — by partisan ID and by vaccination status.

Ironically, the last chart tells the current story (as of early November 2021) about just who is worried about another pandemic in their lifetime — by partisan ID and by vaccination status.

82% of Democrats were concerned about another pandemic like COVID-19 happening in their lifetime compared with 58% of Republicans.

74% of people vaccinated for COVID-19 were concerned about another pandemic in their lifetime, versus 61% of those who had not received a vaccination for COVID-19.

Just as we witnessed and lived through political divides as AIDS emerged in the U.S., we are now in a phase of science-denial among some people.

This is being turbo-charged through social media and networks, which we didn’t have in our daily lives in the early AIDS era.

What we did have was ultra-engaged patients and advocates and families and scientists on the side of managing and, eventually, curing HIV/AIDS. And peoples’ health engagement and advocacy really made a difference in getting therapies to market and reducing (a lot of, albeit not all) stigma.

How will our coronavirus pandemic era play out for these attitudinal differences? Gallup expects the effectiveness of vaccines and therapies’ impacts on variants and peoples’ health outcomes will impact health citizens’ perspectives. I’m not so sure about that: even with all the evidence base, growing by the day, that vaccines protect people from acute illness and death from complications of the coronavirus hasn’t shifted the one-to-two-in-five people in the U.S. who act either vaccine-hesitant or vaccine-rejecting.

Public health communications can learn a lot from the AIDS activism era.

For some sound advice on that score, here’s a piece in today’s Harvard Business Review on public health comms that make great sense to combat “the next pandemic.”

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a