This week, public health truths have collided with social media, the infodemic, and health citizenship.

First, I read in Becker’s Health IT on February 16 that the peer-reviewed policy journal Health Affairs was prevented by a social media outlet from promoting its February 2022 issue themed “Racism and Health.” The company said the topic was too controversial to feature in this moment.

First, I read in Becker’s Health IT on February 16 that the peer-reviewed policy journal Health Affairs was prevented by a social media outlet from promoting its February 2022 issue themed “Racism and Health.” The company said the topic was too controversial to feature in this moment.

“Google and Twitter are blocking its paid media ads to promote the content, flagging racism as ‘sensitive content,'” Molly Gamble explained in Becker’s.

I myself used the blogging platform you’re on now to promote the February ’22 issue of Health Affairs in the Hot Points following my post featuring Abner Mason’s origin story on Love and Health which traced his boyhood in Durham, NC, to founding ConsejoSano, now SameSky Health.

[By the way, what Abner has learned about racism, bias and health along his journey could fill more than a magazine’s column inches).

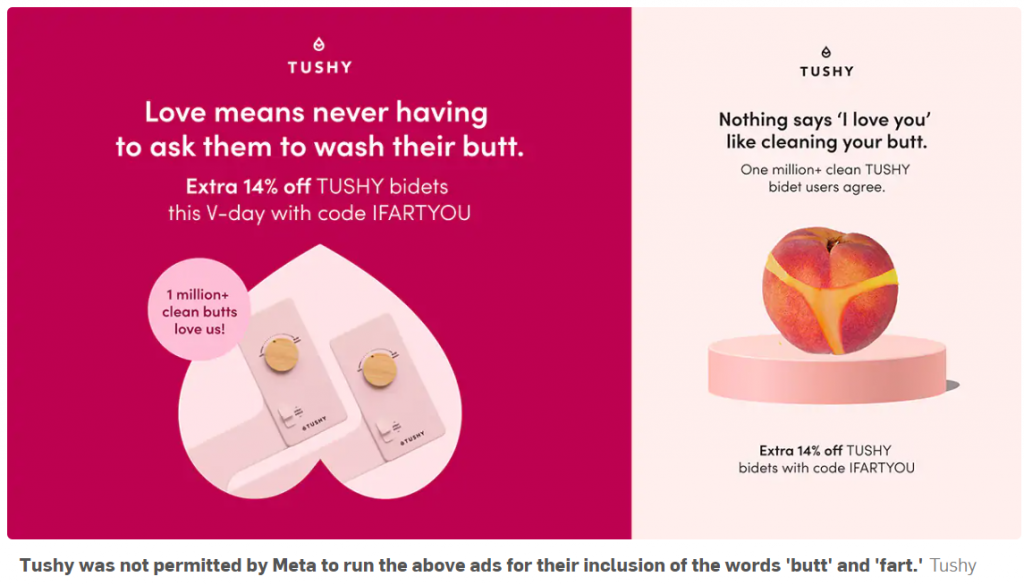

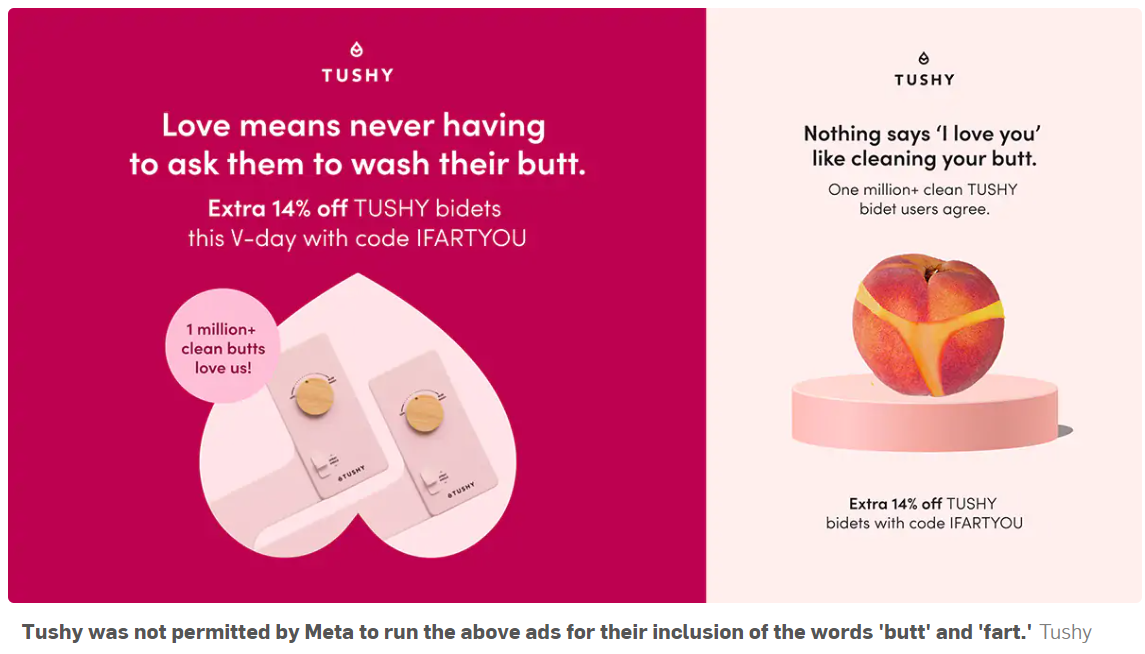

Then I saw an article in Adweek telling me that Meta had banned a Valentine’s Day themed ad from Tushy, discussing how “love means never having to ask them to wash their butt,” and “nothing says ‘I love you’ like cleaning your butt.”

Then I saw an article in Adweek telling me that Meta had banned a Valentine’s Day themed ad from Tushy, discussing how “love means never having to ask them to wash their butt,” and “nothing says ‘I love you’ like cleaning your butt.”

A snapshot of the ad content appears here. While humor and wit are in the eye of the beholder, I truly appreciate the, pardon the pun, cheekiness of the ad copy and attractiveness of the design (plus, a nice 14% off coupon — cleverly taking advantage of Valentine’s Day’s date, the 14th of February).

The topic of personal hygiene and the bathroom as a health destination got more attention at CES 2022 with smart toilets and other self-care products featured.

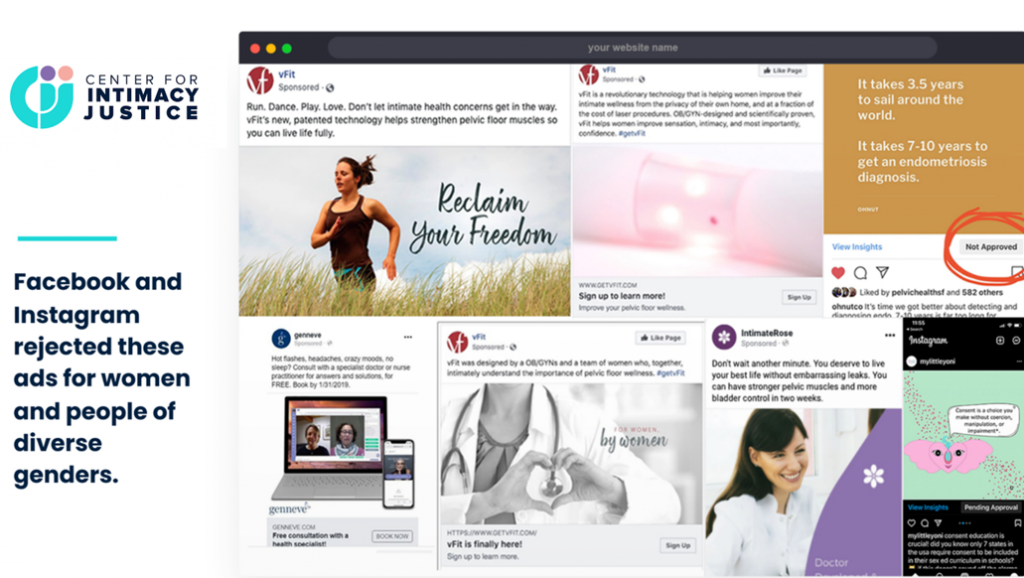

Finally, I read a study from the Center for Intimacy Justice which exposed Facebook’s Censorship of Ads for Women and People of Diverse Genders.

Finally, I read a study from the Center for Intimacy Justice which exposed Facebook’s Censorship of Ads for Women and People of Diverse Genders.

While Facebook and Instagram (owned by Facebook) had accepted a variety of ads for men’s (sexual) health, dozens of ads promoting women’s health (often related to sexuality) had been rejected by the social media platforms.

With social media a very popular channel for communicating health information, Emily Sauer, Founder of Ohnut, responded to the Center’s study noting that, “When we deprive large audiences of sexual health education, we’re also depriving that entire audience of the ability to make choices regarding health.”

Taken together, these three events in social media have unsettled me especially in the context of the recent realities of:

- Joe Rogan, a “drop in the ocean” of medical misinformation, covered here in the New York Times

- Dr. Oz, running for Senate in my home state of Pennsylvania (and widely accused of promoting unproven medical therapies), demeaning Dr. Fauci on Twitter, resulting in a terrific rebuttal from Stephanie Ruhle of MSNBC); and,

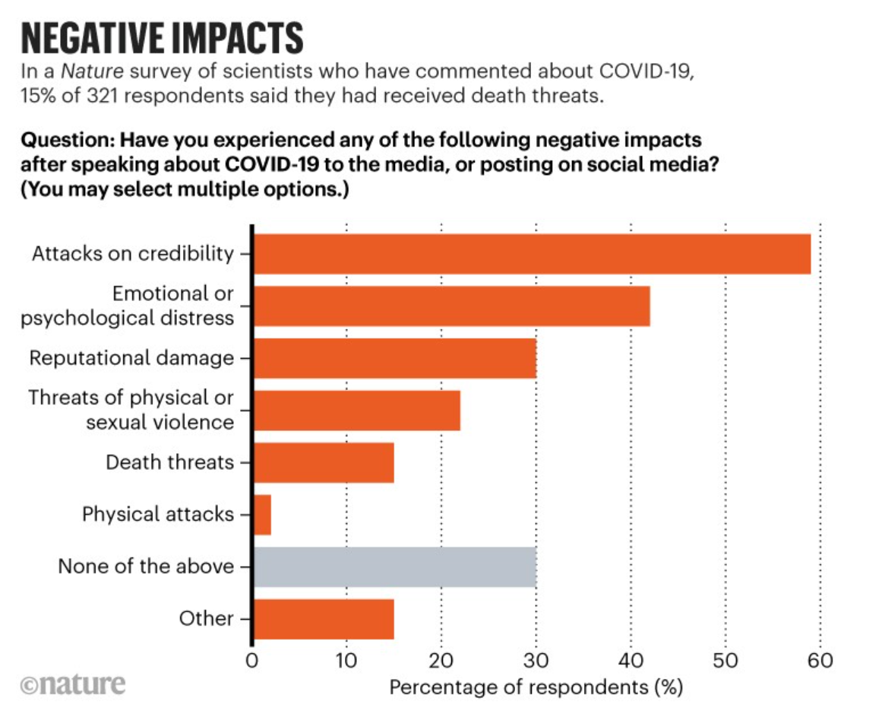

- An escalation during the coronavirus pandemic of scientists being threatened (from reputations to lives), published in Nature.

In the wake of the three stories that introduced this post, these latter three bullet points are just a few current examples I can point to in real-time that don’t sit right with my public health/health citizenship side of my brain and work mission.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: As Cochrane, the organization that provides and advocates for evidence-based medicine and health care, asserts that,

Trusted information needs to be protected on social media as much as misinformation needs to be challenged.

At the same time, speaking the truth about public health, systemic racism, and the importance of personal hygiene — when backed by data and evidence — is at stake in the current upside-down social media landscape.

The World Health Organization has issued a call-to-action to address the infodemic of mis-information that has exploded during the COVID-19 pandemic. WHO defines an “infodemic” as the overabundance of information – some accurate and some not – that occurs during an epidemic. It can lead to confusion and ultimately mistrust in governments and public health response.

WHO is offering an online course on Infodemic Management 101 — that is, how to fight an infodemic. The content was developed by twelve global experts to help us develop skills:

- To analyze the nature, origins and spread of misinformation

- To verify images and video content online and,

- To use social listening tools.

In my work on health citizenship, a key pillar is digital citizenship. A recent article in Social Science & Medicine speaks to The Cultivation of Digital Health Citizenship, arguing that,

In my work on health citizenship, a key pillar is digital citizenship. A recent article in Social Science & Medicine speaks to The Cultivation of Digital Health Citizenship, arguing that,

“Digital health technology can give rise to expressions of altruism, belonging, and demands for recognition and change in healthcare, whilst responsibilising

citizens for the care of themselves and others.”

The authors discuss the concept of “techno-sociality,” as the new social sphere formed by all individual, peer and communal interactions occurring by means of digital technology.

Digital technology generates a “field of rights and responsibility,” including altruism, the authors call out, a sense of belonging to a community, recognitions and demands for change.

In a concise new piece in The Atlantic, Uri Friedman inventories The Seven Habits of COVID-19 Resilient Nations.

Among Friedman’s resiliency strategies, the one that hits home here is the power of countries successfully dealing with COVID-19 who “cultivated public trust in government and fellow citizens.” You can read more about this here on Health Populi when I covered the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer coupled with a recent Lancet study on trust in leaders and public health experts in standing up against the coronavirus.

The promise of digital citizenship must be rooted in eliminating algorithmic bias — to build trust in our health information ecosystem and health care system overall. Furthermore, my pillars of trust and a new social contract of love — for each other, our fellow health citizens — is key to combating future pandemics and building a more civil society. It’s more than time to addressing systemic racism and bias, close the gender disparities in health care and public health, and promote self-care with evidence-based information. Digital technology and social networks can play positive roles in supporting these objectives….with sound design principles (user-centered and privacy-by) and health equity baked in from the inception of the innovations.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for