Among the many lessons we should and must take emerging out of the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding and addressing the caregiver shortage-cum-crisis will be crucial to building back a stronger national economy and financially viable households across the U.S.

And if you thought robots, AI and the platforming of health care would solve the shortage of caregivers, forget it.

Get smarter on the caregiver crisis by reading a new report, To Fix the Labor Shortage, Solve the Care Crisis, from BCG.

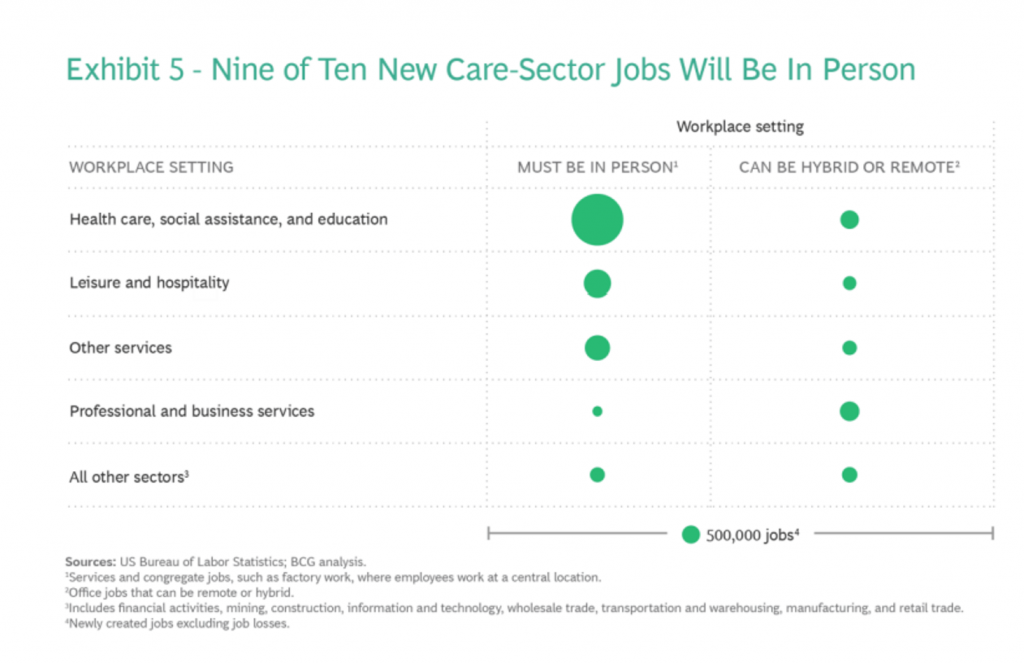

You’ll learn that 9 of 10 new care-sector jobs will be in-person for health care, social assistance, and education — only a fraction of which can be performed on a hybrid or remote basis.

BCG’s top-line is that, “the U.S. desperately needs workers. (And) workers desperately need help taking care of their children and (increasingly), their parents.”

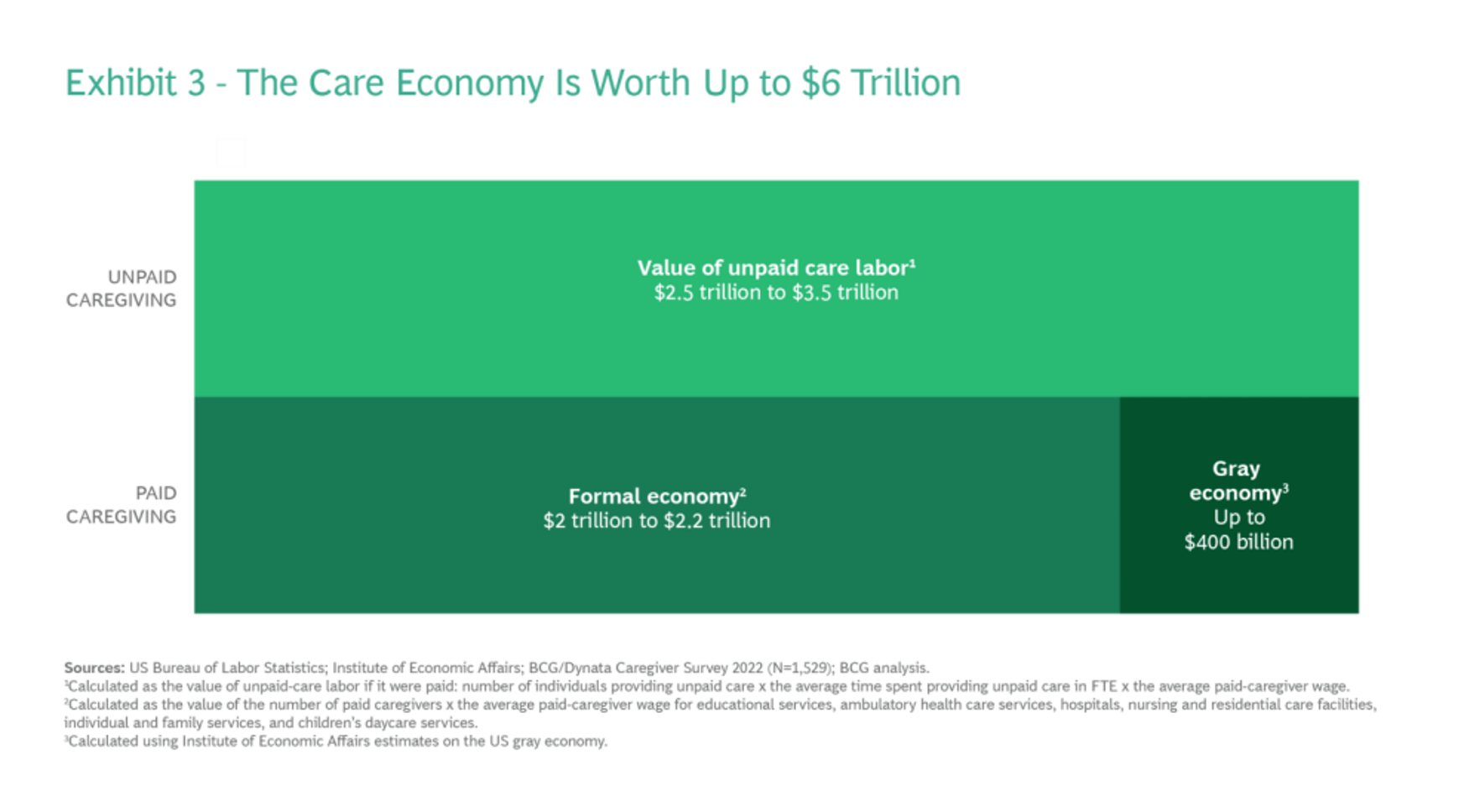

The Care Economy is worth nearly $6 trillion in the U.S., combining both the value of unpaid care labor (between $2.5 and $3.5 trillion) and the formal paid caregiving sector ($2 to $2.2 trillion).

By definition, there are three types of caregivers in the caregiving sector:

Unpaid caregivers, who is anyone with unpaid care responsibilities for children, adult family members, or both, whether they are employed

Employed caregivers, a subset of the unpaid caregivers, who work in the broader economy and also have unpaid care responsibilities for children, adult family members, or both; and,

Paid care workers, who provide care as their occupation. Many also rely on paid care workers for their own family members.

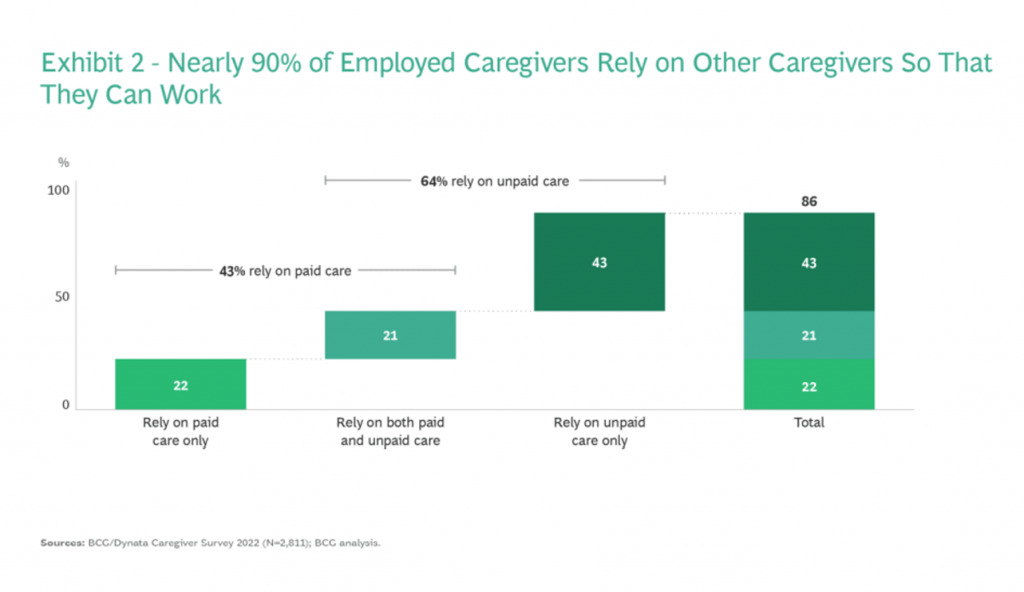

This last point is illustrated in the second chart.

See that 90% of employed caregivers rely on other caregivers so that they can work.

43% rely on paid care, BCG calculated, and 64% rely on unpaid care.

Note the overlap between those who rely on both paid and unpaid care.

The general lesson from the pandemic was the very clear connection between the Great Resignation or Reconsideration and the ability to work-from-home and/or return-to-work.

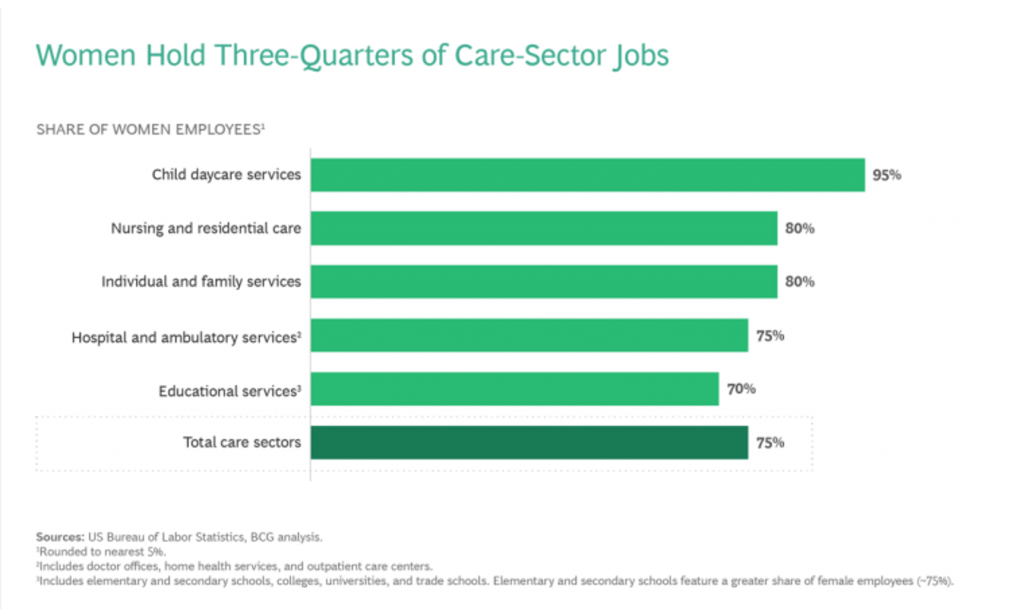

The specific learning underneath that macro reality was that this impacted women more than men in America.

Women hold three-quarters of care-sector jobs, the third chart from BCG’s report points out. Most commonly, these are child daycare service jobs, followed by nursing and residential care and individual and family services, hospital and ambulatory services, and education.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: We are dealing, globally, with a supply chain challenge for basic needs and commodities, like food, energy, home goods and improvement, and even medicines.

We learned tough lessons about the supply of PPE in the initial phase of the pandemic, where Personal Protective Equipment was in short supply.

Even before the coronavirus emerged in early 2020, the U.S. had a supply shortage of nurses and some physician specialties.

And the caregiver crisis was already a huge challenge, all caregivers already knew in 2019 into 2020.

We’re in essentially a supply chain crisis for caregiver human capital.

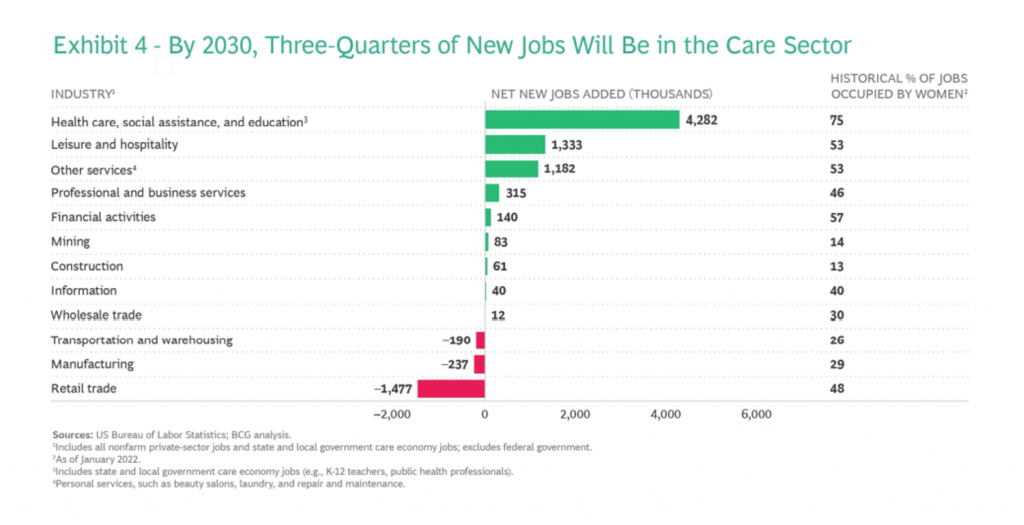

BCG forecasts that by 2030, 3 in 4 new jobs will be in the care sector, the last chart shows. As retail trade, manufacturing, and transportation segments shrink, health and social care jobs explode in growth.

“The numbers tell only part of the story,” BCG explains. “The need for care is a human issue, not a political one. Without affordable, quality care to support those who need it, individuals who want to work will never fully reach their potential — and neither will the US economy, especially as care needs grow.”

The caregiving economy impacts more than the caregiver and her family. The caregiving economy is truly the macroeconomy — either feeding it in a healthy way that serves both the national economy and the individual’s household and family, or slowing macroeconomic growth and personal prospects. The societal risk is furthering disparities in income inequality and health equity, and for women specifically, further erosion of the gains achieve before the pandemic’s She-Cession.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for