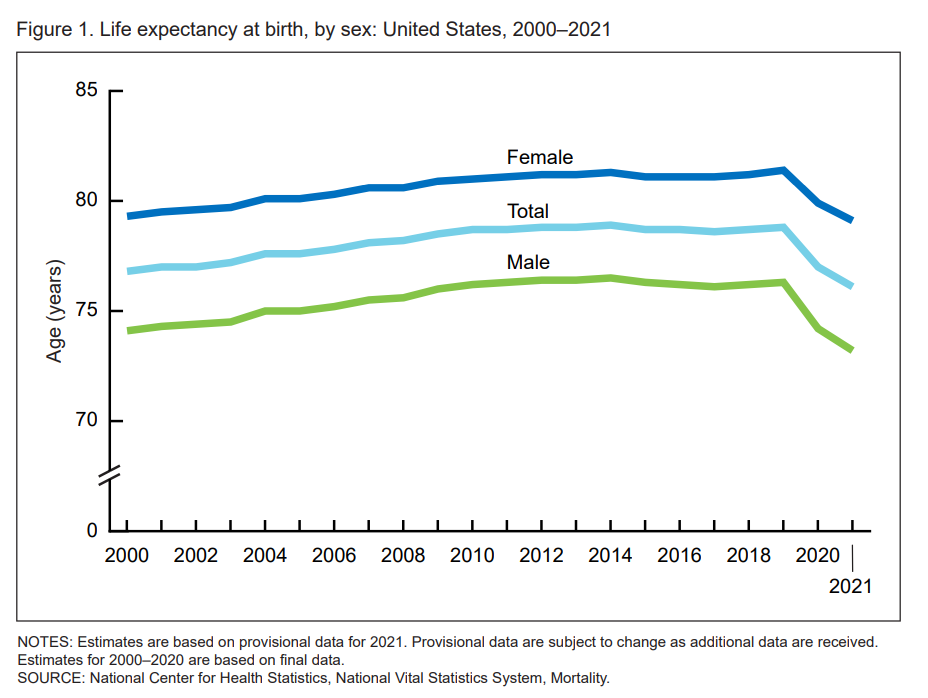

Life expectancy at birth in 2021 in the United States fell to 76.1 years, the lowest level since 1996. Men fared much worse than women, with 73,2 years of life expectancy versus 79.1 years for women, the latest research from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics revealed.

In their Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2021, the CDC kicks off a demographically detailed analysis with this simple line chart which graphs the dramatic decline in life expectancy at birth.

The overall decline across gender and all race/ethnic groups was 2.7 years: 3.1 years for males and 2.3 years for females.

The 2020 to 2021 year-on-year fall in life expectancy was 1.0 year for men, dropping from 74.2 to 73.2; and for women, a decline of 0.8 years, from 79.9 years to 79.1 years.

That’s a difference of 5.9 years between men and women, rising from 5.7 years in 2020 nearly matching the 6-year delta seen in 1996.

For additional context and reality-sobering, note that women’s life expectancy had exceeded 81 years of age from 2010 to 2019, CDC data has tracked.

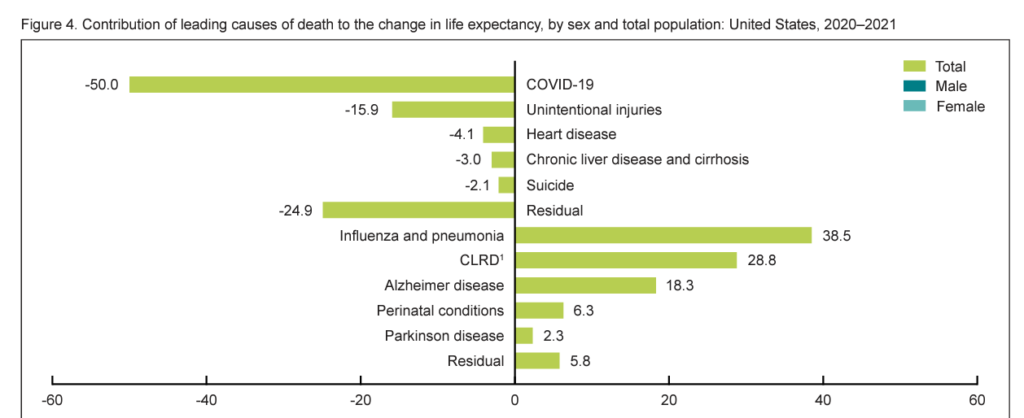

Excess deaths due to COVID-19 and unintentional injuries contributed the most to eroding Americans’ life expectancy between 2020 and 2021.

Unintentional injury deaths were largely due to drug overdoses. The cause was the leading contributor to decline in life expectancy for Hispanic people, and the second-leading cause for people of all other race/ethnic groups except for non-Hispanic Asian people for whom unintentional injuries was the third-leading factor in declining life years.

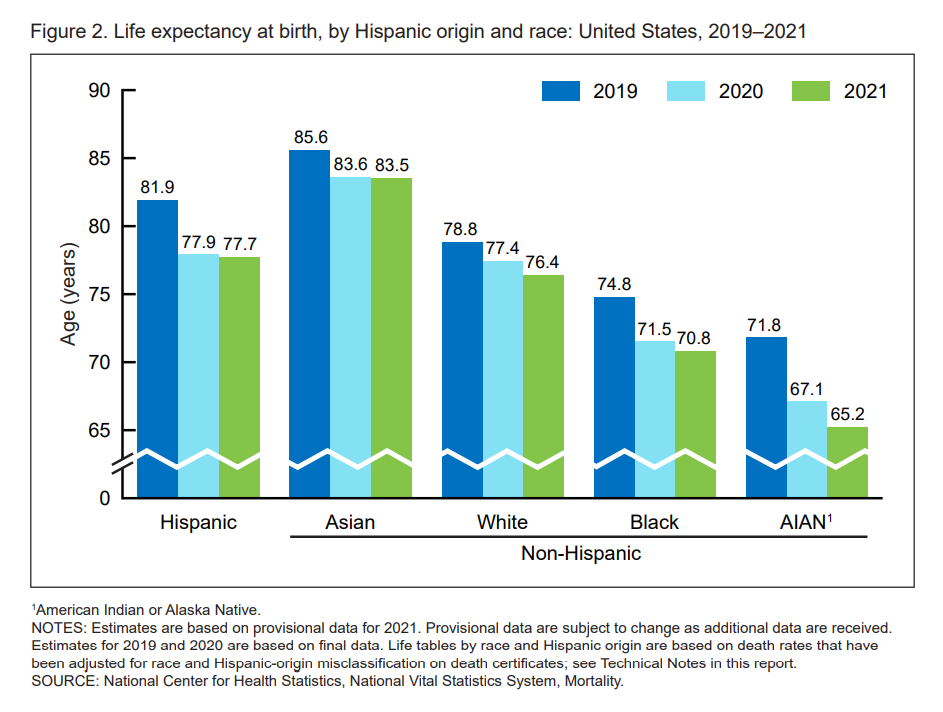

The third bar chart graphs life expectancy from birth by race.

In 2021, the lowest level of life expectancy was among American Indian and Alaskan Native peoples, at 65.2 years — a huge decline of 6.6 years from 2019.

Life expectancy by race/ethnicity fell as follows for U.S. residents:

- To 70.8 from 74.8 for Black people (a fall of 4.0 years)

- To 76.4 from 78.8 for Whites (declining by 2.4 years)

- To 83.5 from 85.6 for Asian folks (falling 2.1 years)

- To 77.7 from 81.9 for Hispanic people (dropping 4.2 years, the second largest year-decline after the AIAN population).

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The larger impact of the coronavirus on life expectancy was seen in 2020 versus 2021, and going forward — with the emergence and use of therapeutics and continued vaccinations — the rate of deaths due to COVID-19 in the U.S. should fall.

But it remains for us to be vigilant about how to deal with other factors eroding Americans’ life expectancy — from the deaths of despair due to drug overdoses, suicide and gunshots, to heart disease and stroke, cancers, and other non-infectious diseases many of which are amenable through addressing key drivers of health: clean water and air (thinking about Jackson, Mississippi, in the moment), food and nutrition security, education (seeing the new study that American children’s math and science scores dropped during the pandemic), and wage and job stability (that determine household and family economic well-being).

When life expectancy declines were announced one year ago by the CDC, the American Medical Association identified strategies to help stem the fall in Americans’ life-years, many of which addressed the drivers of health, civil society, and firearm safety.

In yesterday’s New York Times, Dr. Dave Chokshi, a New York City physician and once NYC health commissioner, offered an op-ed on how we can reverse the fall in life expectancy.

“The decline in life expectancy is not inevitable.” Dr. C wrote. “America is at a fork in the road with respect to the health of the nation…we are at risk of a similar collective amnesia after Covid-19.”

Dr. C’s not so modest proposal was for a sort of modern Metropolitan Health Law at national scale. This Law would recognize that health is tightly linked to economic security, with economic policy viewed as health policy. Such a policy would embed housing, food, and income stability and not have just a simple focus on cash.

Dr C also recommended investing in a national public health corps underpinned by community health workers, especially people residing in marginalized neighborhoods. “Broader preparedness for the next infectious threat must appropriately resource local and state public health agencies, from laboratory capacity to misinformation response,” he recommended.

I leave you with new and inspirational (literally) research on the role of spirituality in health, in this paper focused on a black community participating in the American Heart Association‘s Jackson Heart Study.

Exploring “Religiosity/Spirituality and Cardiovascular Health,” the research found that higher levels of religiosity/spirituality were associated with improved cardiovascular health across multiple indicators, lowering heart disease risk among African Americans.

We can learn from the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 prescriptions for movement and physical activity, eating better, maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding tobacco, reducing blood sugar, controlling cholesterol, and managing blood pressure. “Simple,” and not so simple. It will take public policy, our local communities of trusted touch-points, and valuing the public’s health to reverse the declining levels of life expectancy in the U.S.

And being prayerful may well help, as well.

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast  This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're

This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're