Wisdom from the speech: “But now more than ever before, America is forced to grapple with this problem, for the shape of the world today does not afford us the luxury of an anemic democracy. The price that this nation must pay for the continued oppression and exploitation of the Negro or any other minority group is the price of its own destruction. For the hour is late. The clock of destiny is tickling out, and we must act now before it is too late.”

As I meditate on MLK, I think about health equity, especially potent inspiration in light of Americans’ declining lifespans, tragic maternal and child mortality outcomes, ubiquitous food insecurity, and epidemic mental health crisis.

By now, most clued-in Americans know the score on the nation’s collective health status compared to other developed countries — especially striking differences between black people and whites in death rates and complications due to COVID-19.

Suffice it to say, We’re Still Not #1 for health outcomes, albeit we’re the biggest spender on healthcare, per health citizen, in the world.

Underneath that statistic is a shameful state of health affairs: that people of color and the LGBTQ communities in the U.S. have lower quality of health and many services than white people do:

- Black women have higher breast cancer death rates than White women

- Asian women are less likely than White women to receive a pap smear

- Hispanic women are more likely than non-Hispanic White women to be diagnosed with cervical cancer at an advanced stage

- Rates of hospital admissions for uncontrolled diabetes are higher for Black women than for women in other racial/ethnic groups

- The rate of hospital admissions for lower extremity amputations due to uncontrolled diabetes is higher for Black women than White women

- The rate of new AIDS cases is higher for Black and Hispanic women than for non-Hispanic White women. Black and Hispanic men had even higher rates than women, as well as higher rates than non-Hispanic White men

- Black women receive treatment for depression less frequently than White women and Hispanic women received treatment less frequently than non-Hispanic White women

- Hispanic women received treatment for substance abuse less frequently than non-Hispanic White women.

If these statistics don’t move you, then here’s a finding from the National Academy of Science’s Shorter Lives, Poorer Health that might surprise you: today, people in the U.S. under 50 have poorer health outcomes than our cohorts in other developed countries. For women under 50, we’d rather live in other industrialized countries where fewer women under 50 die from noncommunicable diseases, heart disease, injuries, perinatal conditions, drug-related causes, and communicable and nutritional conditions.

Yes, more younger women in the U.S. — the wealthiest nation in the world — lose more life-years due to malnutrition, infectious disease, injury, and lifestyle-borne diseases like diabetes and heart disease than in our fellow rich countries.

And in 2018, a new statistic emerging that the rate among women for deaths due to opioid overdoses rose. One of the most heartbreaking aspects of this concerning trend is a link to pregnant women and newborns.

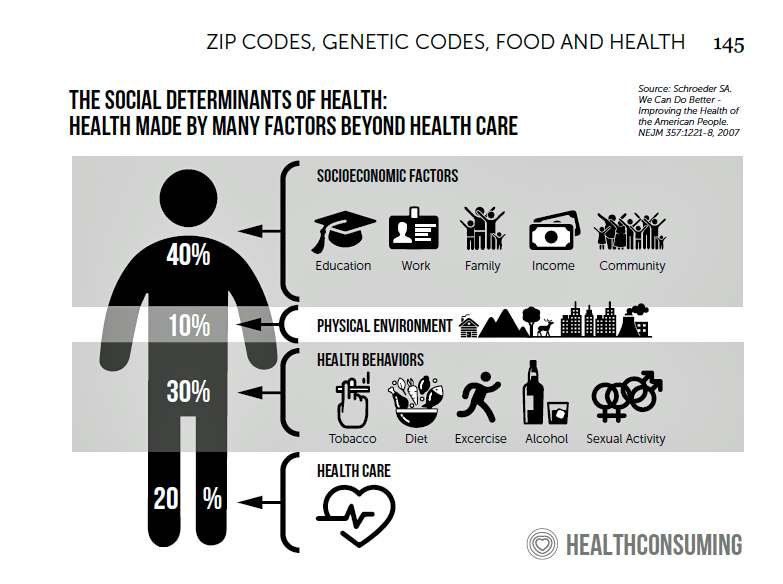

What’s new today versus previous MLK Days is that the rate of white male middle-age deaths is on the rise, as well. So when we consider health disparities and public health, it’s important to realize there’s one boat, one health commons, and every person in America is impacted by those social determinants of health beyond the healthcare system: clean air (ask a aging miner in West Virginia), clean water (ask your cousin in Flint, Michigan or Newark, NJ), good jobs (with health benefits – ask any worker without them), nutritious food (ask someone living in a food desert), social connections (ask an isolated senior), and in my growing appreciation, access to connectivity/broadband networks (ask anyone looking for a job or a clinic for a lab test without a good smartphone data plan).

In 2019, an emerging concern is how the growth in adoption of artificial intelligence and cognitive computing among health care organizations – particularly, insurance plans, providers, and pharma. AI can be used for good, to be sure. The promises of Big Data in health cover a wide range: hospitals anticipating and preventing inpatient readmissions; health plans deploying more effective population health programs; and research-based life science companies being more intelligent and efficient in finding cures.

But AI also can mine data from sources beyond the medical claim that mashed together profile people in ways that can be used to bias business choices in the interest of cost-saving or simply-put, prejudice. We must guard against exacerbating health disparities with these sorts of AI applications in health and medical care.

A recent U.S. District judge ruling against the Trump administration’s decision to add a citizenship question to the 2020 U.S . Census is another example of how institutions, and public ones at that, can try to mis-use data or mis-appropriate data. For an in-depth look into this phenomenon, see my report, Here’s Looking at You: How Personal Health Information is Getting Tracked and Used, written for the California Healthcare Foundation.

Finally, read what U.S. doctors have to say about health disparities in JAMA. The top line for doctors lies in the concluding sentence: “Apart from the human and economic consequences affecting today’s adults and workforce, the health disadvantages faced by today’s children carry profound implications for tomorrow’s adults, the nation’s economy, and national security. Now the question is what US society is prepared to do about it.”

To this end, I am encouraged (immediate-term, anyway) by the growing understanding and embrace of the role of social determinants for health in America among both providers and health plans.

Coming full circle to Dr. King, there’s a paragraph from MLK’s speech delivered at the Great March of Detroit that especially resonates on his special Day:

“We are coming to see now, the psychiatrists are saying to us, that many of the strange things that happen in the subconscious, many of the inner conflicts, are rooted in hate. And so they are saying, ‘Love or perish.’ But Jesus told us this a long time ago. And I can still hear that voice crying through the vista of time, saying, ‘Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, pray for them that despitefully use you.’”

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I am a child of metro Detroit. As a very little girl, I lived through the Detroit Riots of 1967, a few days after which my father drove us through the fire-devastated neighborhoods of his friends and clients who lived and worked around 12th Street and Grand River. It was a visceral moment for me in my life, one of my earliest memories, seeing burned-out shops on pedestrian main streets. I remember still the smoky smell which my young lungs breathed in. I wondered why something like this happens.

In a few years’ time, I was reading Martin Luther King’s book, Why We Can’t Wait; The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Native Son by Richard Wright — still, one of my favorite books. In college, I delved deeply into urban economics and urban planning, soaking in Jane Jacobs’ seminal work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, among other influential books on the syllabus.

At the University of Michigan School of Public Health, I then learned to connect the dots between our environment, our socioeconomic status — especially the role of education — and health.

Addressing health disparities is as much about access to health insurance as it is to access to good and well-priced food, safe schools, education, good jobs, and sound social policies about gun ownership and use. We must also attend to seeing that broadband and connectivity, and net neutrality for access to the online world, services, and communities, are guaranteed to all health citizens in America.

These interrelationships are fundamental to public health thinking. Those of us whose work touches any aspect of health and health care must attend to public health and commit to reducing health disparities in America. A healthy populace is more productive across so many dimensions. As we continue the hard work to re-build the national economy and continue to expand affordable health care access, public health should and must be seen and used as a pillar for economic growth.

This was a key call-to-action I raised at the conclusion of my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen,most Americans, having morphed into payors and consumers, see health care as a human or civil right. As health citizens, people in America would be covered by universal health insurance and more comprehensive data privacy protections. That’s the rights side of the civics ledger. On the responsibilities side, Americans must become more politically engaged, embracing their role as citizens and the blessings of the freedom to vote and engage in public policy in the commons. That’s what MLK would have wanted.

In my most recent book, Health Citizenship: how a virus opened hearts and minds, I am even more pointed based on what we’ve experienced during the public health crisis, the summer when George Floyd got more white people woke, and the pandemic economy hurting people of color more than white folks. Health citizenship has four pillars: health care as a civil right, digital citizenship and privacy rights of personal information, trust (in science, in each other), and a new social contract — which is love in the Age of the Coronavirus.

My friends, it does seem dark right now at the convergence of so many crises — the pandemic, the economy, social and civil rights, and most recently a crisis of confidence in democracy.

But as MLK, Jr., said in his book, All Labor Has Dignity…”I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.”

This post was updated from previous versions that have run here on Health Populi to commemorate Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, birthday and America’s National Day of Service.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for