For health care, AI can benefit diagnosis and clinical care, address paperwork and bureaucratic duplication and waste, accelerate scientific research, and personalize health care direct-to-patients and -caregivers.

On the downside, risks of AI in health care can involve incomplete or false diagnoses, inaccuracies and errors in cleaning up paperwork, exacerbate differential access to scientific knowledge, and exacerbate health disparities, explained in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) report, Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health.

WHO has released guidance on the use of large multi-modal models (LMMs) in health care which detail 40+ recommendations for stakeholders in the field to consider when deploying AI.

WHO calls out the power of LMMs’ ability to take in all kinds of data for health and medical care — text, images, videos, all available in people’s medical records, radiology imaging systems, prescription drug databases, and consumers’ own self-generated data based in health-app clouds and GPS check-ins.

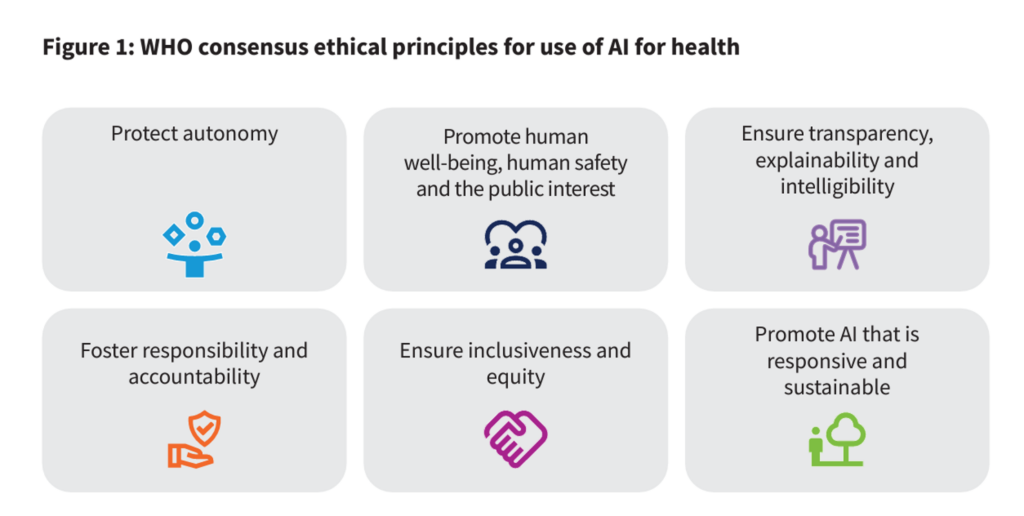

Weighing the benefits and risks of AI in health, WHO offers up six ethical principles to keep in mind:

- To protect autonomy

- To promote human well-being, human safety, and the public interest

- To ensure transparency, explainability, and intelligibility

- To foster responsibility and accountability

- To ensure inclusiveness and equity, and,

- to promote AI that is responsive and sustainable.

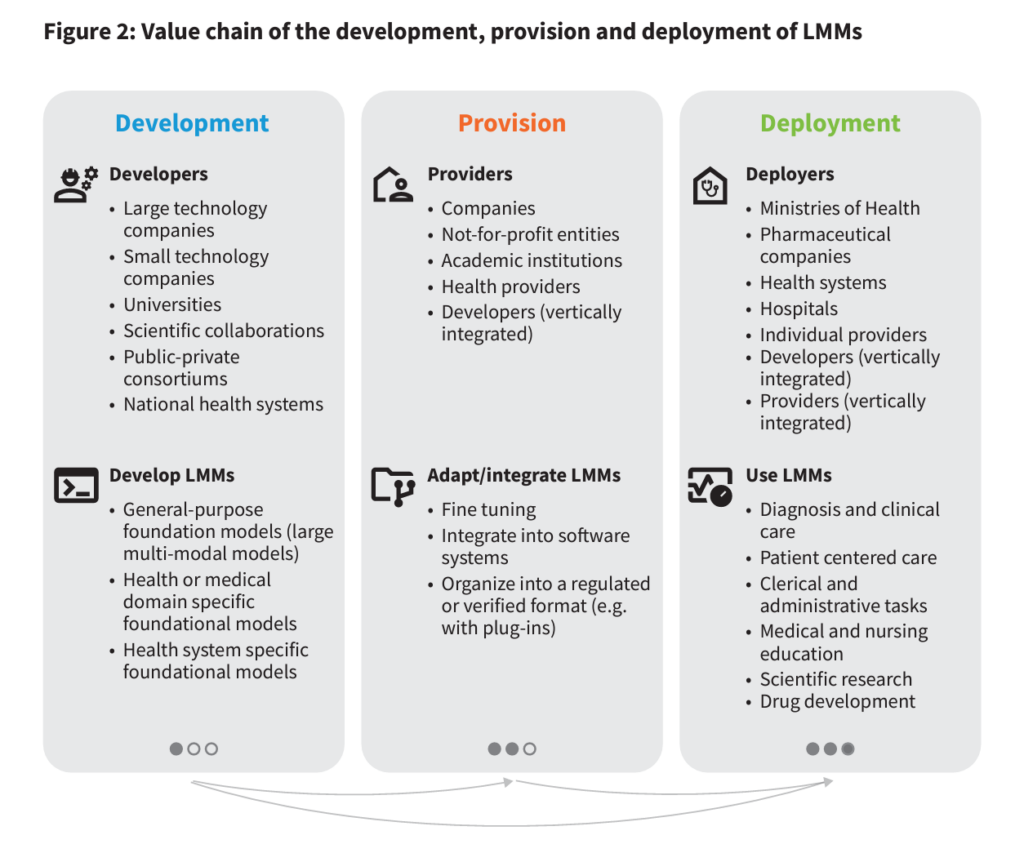

Figure 2, shown here from the report, helps us understand the community of stakeholders in health/care who will be involved with AI. The list is long and diverse, and illustrates the reach that AI will have on people’s personal health and well-being — as well as the importance of the ethics that these stakeholders embrace. These stakeholders are involved in various parts of the AI+health care value chain, from development to providing services to implementing information and ongoing research.

On the development front, note large and small technology companies, universities and academic medical centers (AMCs), large health systems, and various collaborations (private, public, and hybrid) are all involved in developing the LMMs.

For provision, we look at for-profit companies, not-for-profit organizations, AMCs, other providers, and developers integrated into care delivery systems.

Moving to deployment and implementation, we can consider health ministries and departments, pharma and life science companies, health systems and hospitals, individual providers, and the developers and providers integrated into health systems.

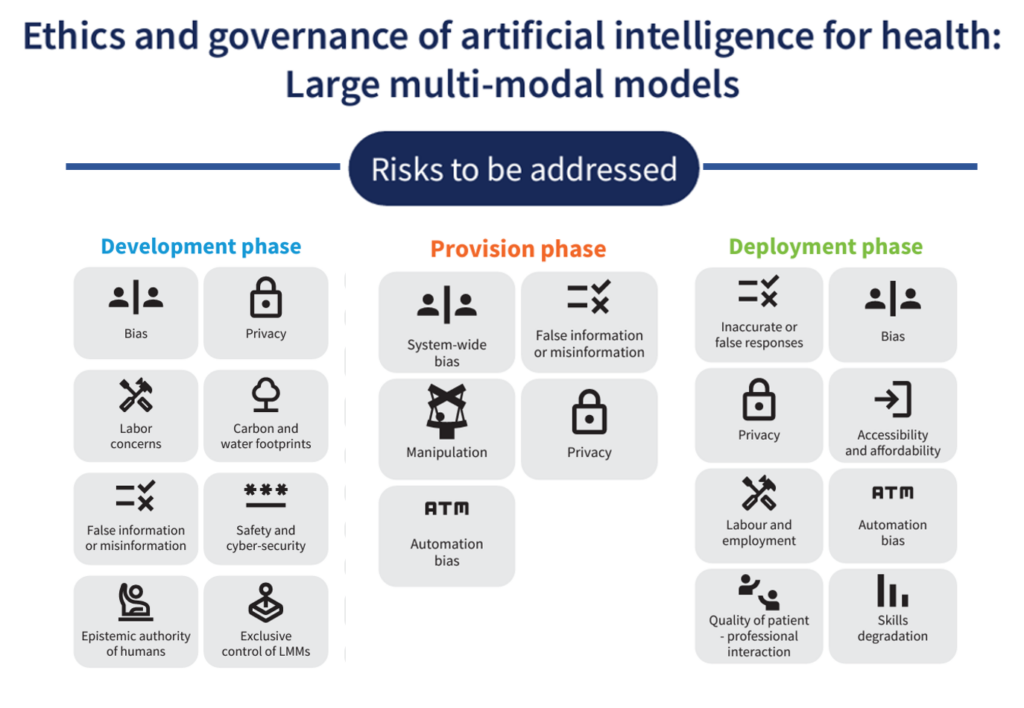

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I’ve summarized WHO’s list of risks to be addressed by each of the three value-chain stakeholder groups to give us a sense of the many potential unintended outcomes that could result from the development and use of LMMs and Ai in health care.

Consider just one risk from each of the 3 areas:

- In the development phase, the concerns of the labor force — much of which is already feeling burnout and alienation from their fields of work

- In the provision phase, challenges of data manipulation and mis-information

- In the deployment phase, issues of automation bias and bias in general.

As you continue to debate the role of AI in your health/care work, as well as develop your organization’s strategy and staff complement, the WHO report (through this lens) gives us some insights into how to optimally approach governance when moving forward in this next phase of health care innovation. Adopting principles of equity-by-design and privacy-by-design will help us along the journey.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a