Health literacy and, indeed, literacy across the many layers relevant for health (digital, medical, financial), is a challenge for people of all ages.

The Institute for Healthcare Policy Innovation’s National Poll on Healthy Aging at the University of Michigan focused on people 50 and over in their latest study published this month: Health Literacy – How Well Can Older Adults Find, Understand, and Use Health Information.

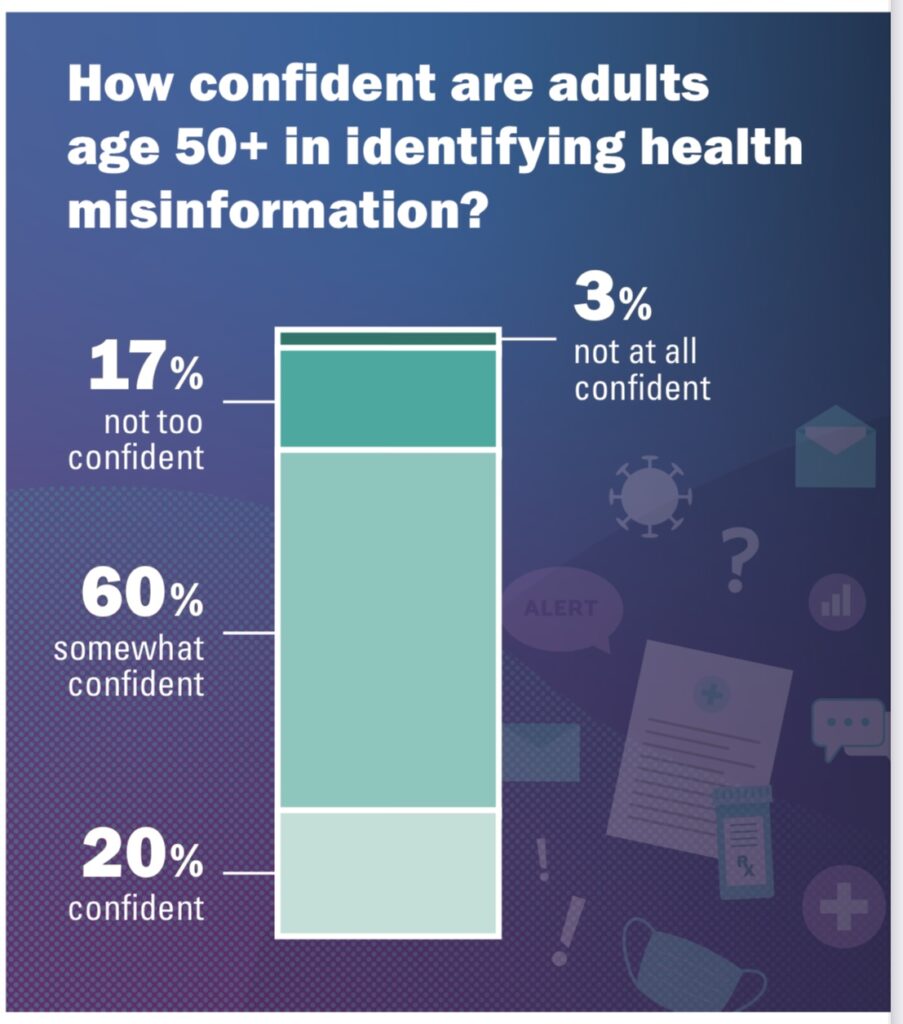

On the upside, 4 in 5 older people (50+) feel confident in being able to spot health mis-information, the chart from the Poll report clearly tells us. 20% of older U.S. health citizens are confident, and 60% say they’re “somewhat confident.”

That leaves 20%, 1 in 5, older people not confident in identifying health mis-information. These folks self-report themselves as having a poor memory (35%), failing physical health or mental health (28%), or a disability that limits their activity (25%).

Where do these folks get their health information? 4 in 5 told U-M they get health information from the Internet or from health care providers. 42% received health information from pharmacists, and another 18% from family or friends with a health background.

Among Internet-based sources, the top-searched sites were general health and health condition-specific sites like WebMD or Healthline, among 39% of older people. 31% of these consumers sought information on websites run by health care systems (such as Mayo Clinic or Cleveland Clinic). Surprisingly, fewer sought health information from advocacy and associations such as the American Heart Association or American Cancer Society (14%). 21% went to Federal government agencies.

Social media sites as a research destination garnered only 6% of older peoples’ health information seeking,

Feeling confident and empowered to identify misinformation would be a factor for trusting that information.

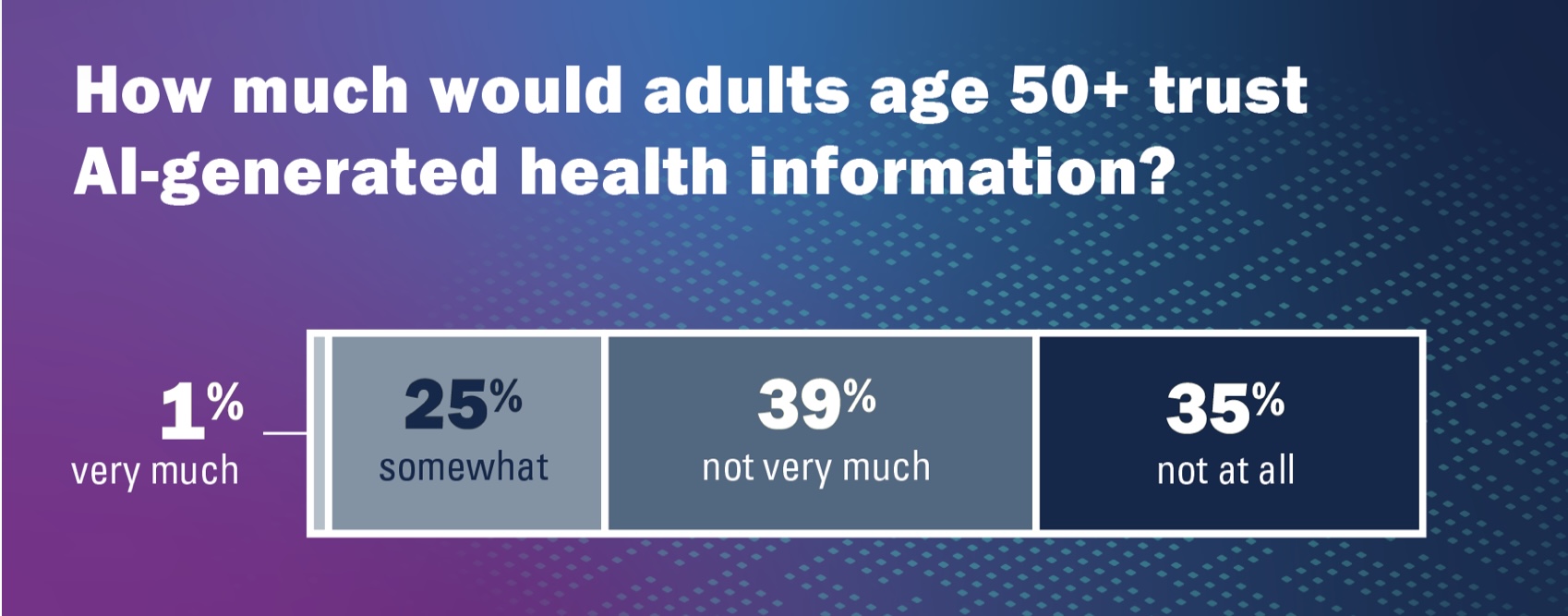

When it comes to AI-generated health information, though, the U-M Poll unearthed an important nuance: that 3 in 4 older U.S. health citizens do not trust AI-generated health information.

Older people less likely to trust AI-generated health data were women, people with lower household incomes (<$60K), and people who did not have a health visit in the past year.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: At yesterday’s OSF Digital Health Summit, one of the questions during my keynote’s Q&A session came from a health care professional who is helping launch a new ambulatory care center focused on patients 55 and over in Illinois, to open in January 2025. Her question involved an app the team is developing, as part of the overall patient engagement information infrastructure, and how the organization could further build trust among these patients to inspire them to engage with the app, their personal health information, and the organization.

The U-M Poll report echoes some of my advice:

“Amid (this) lack of trust, our findings also highlight the key role that health care providers and pharmacists play as trusted health messengers in older adults’ lives, and even the role that friends or family with medical backgrounds can play,”

according to Jeffrey Kullgren, MD, MPH, MS, who is a primary care physician with the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and associate professor of internal medicine at U-M.

He added, “We also find that websites run by health organizations are seen by most who use them as very trustworthy.”

In our discussion at OSF, I also discussed new relationships in collaborating in digital health innovations to bolster trust with patients and clinicians. Trusted touch points in older peoples’ communities — near their homes, close to homes such as faith-based organizations, senior centers, public libraries, the local Y, the barber and beauty shop, and other places where “haloes of trust” can benefit health care providers and systems, are important partners in health and wellbeing.

On the AI front, we have a new challenge to embrace and address in communicating, in Main Street language with respect and authenticity, the promise of what AI can bring to health care and our personal health, and the potential drawbacks and limitations in terms of potential biases and inclusion in algorithmic databases.

In these cases, health literacy takes a carefully-curated village to re-build trust which has eroded between patients and the health care industry over the past few years.

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a