The partisan divide in the U.S., exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, could set the stage for another public health emergency given eroding trust in institutions — especially in media, government, and public health officials.

I base this sobering forecast on the latest study from the Pew Research Center which polled people in the U.S. about their pandemic-perspectives, detailed in the report 5 Years Later: America Looks Back at the Impact of COVID-19. Couple these findings with the recent dismissal of public health “disease detectors” working with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and what is currently termed a “quademic” (that is, the convergence of 4 viruses, worsened in winter season), could escalate into America’s next public health emergency especially driven by one of those four viruses, the bird flu, H5N1.

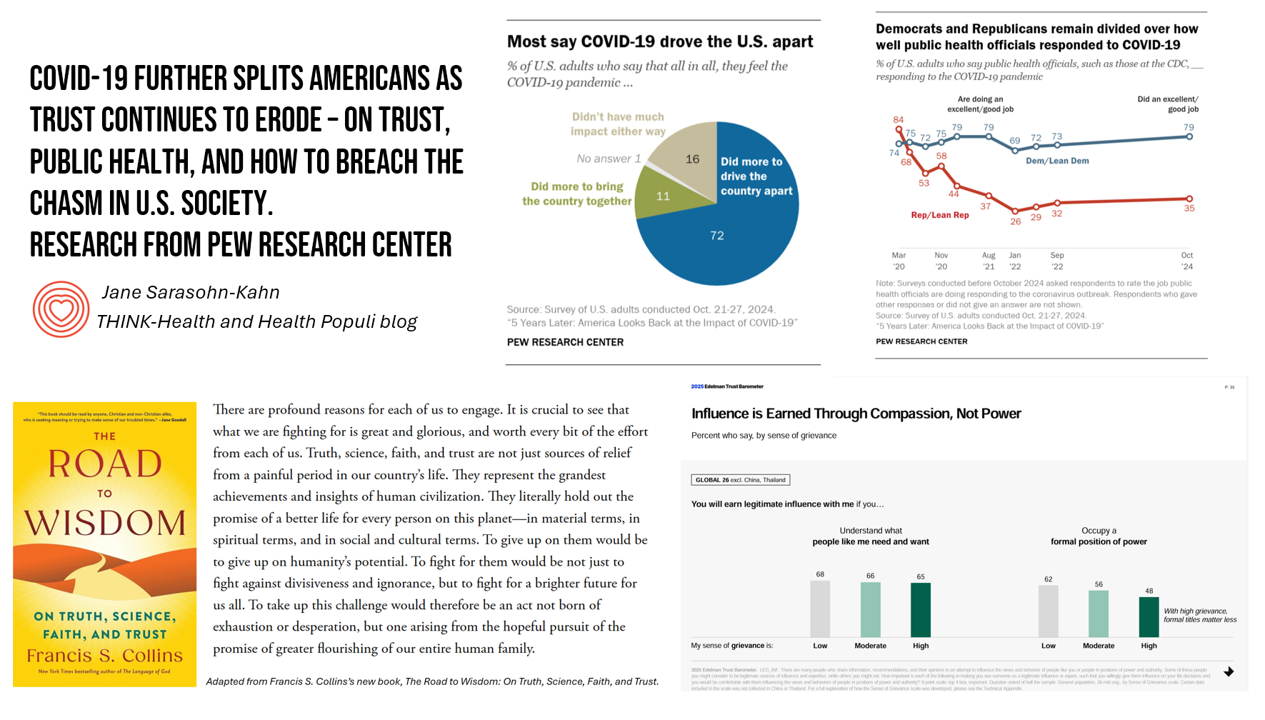

Most Americans say that COVID-19 drove the nation apart. The Pew team calls out important context setting the stage for this societal chasm as the pandemic emerged in the U.S. These three factors already in play that were re-shaping America and Americans were,

- A growing partisan divide

- Eroding trust in institutions, and,

- “Massive splintering” of the information sources (think: podcasts, mass media fragmentation, and the erosion of trust in media, as well embedded in #2, above).

About 3 in 4 people said the pandemic took a toll on them — while 44% of people believe they have “mostly recovered,” 30% report feeling they have not at all recovered or somewhat recovered.

To this point on information and media’s eroding trust, this chart from the study illustrates the partisan divide between folks who identify or lean as Republican compared with people who identify or lean Democrat. Overall, 55% of U.S. adults thought the media exaggerated the risks of COVID-19.

By party…80% of the Republican cohort (net lean + GOP) say the news media exaggerated the risks of COVID-19 in their reporting versus 30% of those in the Democratic group (lean + Dem).

One-half of the Dem group thought the media got the risks about right compared with only 31% of the GOP group.

There were additional data points illustrating the chasm between partisans in the U.S.:

- 76% of the Dem/Lean Dem group say that the coronavirus today is worse than a cold or flu versus 36% of Rep/Lean Rep Americans

- Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say it’s important to avoid contact with vulnerable people when they have cold-like symptoms. Furthermore, 60% of Democrats say it’s important for people to wear a mask in crowded settings if they have cold-like symptoms versus only 26% of Republicans.

- 57% of Democrats would take a COVID-19 test if they had cold-like symptoms versus 25% of Republicans

There are also stark partisan differences in how Americans believe public health officials responded to the pandemic, shown in the divergent line chart: the blue line representing the Democrat group largely views the public health responders did an excellent or good job.

Only 35% of Republicans believe the public health officials did that excellent or good job in dealing with COVID-19.

Consistent with this rift, Pew found that most Republicans said there should have been fewer restrictions in their area during the pandemic:

- 62% of Republicans said there were too many restrictions on public activity compared with

- Only 15% of Democrats who would have liked fewer restrictions.

Pew fielded this survey among nearly 9,600 U.S. adults in late October 2024, with additional polling conducted earlier in October among about 5,300 U.S. workers.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Francis Collins ran the National Institutes of Health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

All the while, as one of the lead scientists in America, Collins was also a devout Christian, balancing science with faith, truth, and trust in his heart and head.

His latest book, The Road to Wisdom, was published in September 2024. In it, Collins recounts his experience leading NIH while dealing with the coronavirus, and confesses to us mistakes that were made in how America’s lead scientists, at least those in the Federal government involved in pandemic communications, failed to articulate some major messages with the U.S. public that would connect with people.

Eroding trust in government, media, and public health officials was already a dynamic in late 2019-early 2020, as I discussed here in Health Populi in the context of the 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer. That year, just prior to the pandemic emerging in the U.S., income inequality was fanning the distrust phenomenon as a “mass-class trust divide,” as Edelman coined the situation. That year, the key trusted touchpoints were experts working in companies as technical experts (think: bench scientists in pharma R&D) and in academia.

This was not the case five years later, Edelman learned earlier this year in the 2025 update: in this year’s mood seen as a Crisis of Grievance, most people were looking for compassion as a place of influence — not a formal position of power. Roughly two-in-three people across the “grievance scale,” whether low or high, said they could feel legitimate influence if an organization or stakeholder understand “what people like me need and want.”

To Francis Collins’ point in The Road to Wisdom: “Trust, science, faith, and trust are not just sources of relief from a painful period in our country’s life. They represent the grandest achievements and insights of human civilization. They literally hold out the promise of a better life for every person on this planet….To give up on them would be to give up on humanity’s potential. To fight for them would be not just to fight against divisiveness and ignorance, but to fight for a brighter future for us all.”

In re-building trust in science, public health, and health care in the U.S. (and throughout the world), we must lead with compassion, empathy, and deeply understanding what people really need and want. Call on the storytellers, the UX designers and anthropologists, the marketers with heart and analytic skills.

Here’s one wonderful example from Canada to learn from: with faith-based institutions bolstering health literacy, trust, and vaccination rates.

Why does this work?

“Many religious leaders and communities worldwide actively promote vaccination, seeing it as a moral obligation to protect not only individual health but the well-being of the community…as an act of love and social responsibility to protect vulnerable members of society. Religious leaders are often highly trusted figures within their communities with a potent ability to influence attitudes and behaviors….Engaging faith leaders isn’t about co-opting religious authority, it’s about building bridges and creating culturally sensitive, respectful communication,”

the researchers from Simon Fraser University explain.

The prescription: “Collaboration is key.”

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast  This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're

This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're