This past weekend, 60 Minutes’ Leslie Stahl asked John Castellani, the president of PhRMA, the pharmaceutical industry’s advocacy (lobby) organization, why the cost of Gleevec, from Novartis, dramatically increased over the 13 years it’s been in the market, while other more expensive competitors have been launched in the period. (Here is the FDA’s announcement of the Gleevec approval from 2001).

This past weekend, 60 Minutes’ Leslie Stahl asked John Castellani, the president of PhRMA, the pharmaceutical industry’s advocacy (lobby) organization, why the cost of Gleevec, from Novartis, dramatically increased over the 13 years it’s been in the market, while other more expensive competitors have been launched in the period. (Here is the FDA’s announcement of the Gleevec approval from 2001).

Mr. Castellani said he couldn’t respond to specific drug company’s pricing strategies, but in general, these products are “worth it.”

Here is the entire transcript of the 60 Minutes’ piece.

Today, Health Affairs, the policy journal, is hosting a discussion of the publication’s analyses into specialty pharma — including policy initiatives, the role of coupons, and specialty Rx as driver of health costs. I’m observing the tweets while traveling to a client via Amtrak, and have read 3 of the articles to gain insights into the latest thinking on this very important topic for individual and public health.

Today, Health Affairs, the policy journal, is hosting a discussion of the publication’s analyses into specialty pharma — including policy initiatives, the role of coupons, and specialty Rx as driver of health costs. I’m observing the tweets while traveling to a client via Amtrak, and have read 3 of the articles to gain insights into the latest thinking on this very important topic for individual and public health.

First, a definition to set us on the same playing field: specialty pharmaceuticals are novel drugs and biologic agents that require special handling and ongoing monitoring, are administered by injection or infusion, and are sold in the marketplace by a small number of distributors, according to Bradford Hirsch and colleagues at Duke University, who penned one of the three seminal research articles in the October 2014 Health Affairs issue called The Impact of Specialty Pharmaceuticals As Drivers of Health Care Costs.

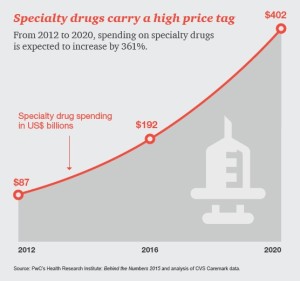

Hirsch et al note that there’s no clear definition of “specialty pharma,” but that all roads lead to one key differentiator: that these products cost payers and patients $600 or more per treatment (dose). They are “special” in that they are very expensive relative to other general pharma products, such as those proferred to deal with diabetes, heart disease, and respiratory conditions. As the chart from Express Scripts shows, therapy classes for specialty pharma include inflammatory conditions, MS, cancer, HIV, Hep C, and other high-cost conditions. Express Scripts’ data here also charts the growth of specialty drug spending to 2015 by category.

Hirsch and his team lay out the big picture in terms of macro health costs: specialty pharmaceuticals could account for 50% of drug spending by 2019. In oncology, every product approved by the FDA in 2012 was priced over $60,000 for one year of therapy. These products included Zaltrap, the highest-cost treatment exceeding $120,000 for a year; Kyprolis, also, over $120K, Stivargo just aroudn $120K; and, 9 others ranging from nearly $70,000 to just under $120,000 for a year’s treatment.

Hirsch and his team lay out the big picture in terms of macro health costs: specialty pharmaceuticals could account for 50% of drug spending by 2019. In oncology, every product approved by the FDA in 2012 was priced over $60,000 for one year of therapy. These products included Zaltrap, the highest-cost treatment exceeding $120,000 for a year; Kyprolis, also, over $120K, Stivargo just aroudn $120K; and, 9 others ranging from nearly $70,000 to just under $120,000 for a year’s treatment.

A third article in Health Affairs talks about the role of coupons for discounting patients’ out-of-pocket costs, which can improve adherence (that is, patients’ sticking to a treatment) by shielding them from higher costs. At the same time, Catherine Starner and her co-writers point out, couponing can also incentivize patients to use higher-cost drugs when a lower-cost alternative could work at least as well.

Health Poupli’s Hot Points: Consider the prices for the 2012-approved oncology products in the context of overall health spending. At these prices, the $120K price tag is at least 60 times the cost of a day’s stay in an inpatient hospital bed, averaging just over $2,000 in 2011 according to Kaiser Family Foundation statistics.

This begs the question, then, how to re-allocate the health care dollar across inpatient, outpatient, home care, pharma and other health cost line items in the era of expensive specialty drugs. And, how to ensure that patients can access these “financially toxic” costs, as coined by Dr. Leonard Saltz of Memorial Sloan-Kettering, interviewed by Stahl in the 60 Minutes story.

Put another way, what is the value of human life at what might be the end-of-life, when some of these products might add one or two additional months of life?

As patients continue to morph into health care consumers, responsible for paying for 20, 30, 40 percent or more of the retail price of specialty drugs, the patient and her family are faced with spending very real money by any definition. This isn’t your father’s co-pay for an unbranded brand of an inhaler for COPD for, say, $60. This is, on an annual basis, a downpayment on a house, a couple of years of college tuition, or a parent’s financial legacy in an estate to his/her children.

At the same time, as James Robinson and Scott Howell observe in another Health Affairs article on policy initiives for pricing specialty drugs, “physicians play a central role in determining the value of specialty pharmaceuticals.” This calls for doctors to play a part-time but crucial role in shared-decision making with patients, wearing the new hat as a health economist-cum-personal-financial-planner (a topic about which I frequently write, such as here in Health Populi).

Thus, the AMA has begun to offer guidelines and training to teach physicians to weigh the costs of care, in order to become better stewards of medical resources.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a