There’s a trifecta of books written by three brilliant doctors that, together, provide a roadmap for the 21st century continuum of health care: The Patient Will See You Now by Eric Topol, MD; The Digital Doctor from Robert Wachter, MD; and, Being Mortal, by Atul Gawande. Each book’s take provides a lens, through the eyes of a hands-on healthcare provider, on healthcare delivery today (the good, the warts and all) and solutions based on their unique points-of-view.

This triple-review will move, purposefully, from the digitally, technology optimistic “Gutenberg moment” for democratizing medicine per Dr. Topol, to the end-game importance of conversation, personal stories and spirit — what Dr. Gawande says is the real job of the medical profession, enabling peoples’ well-being.

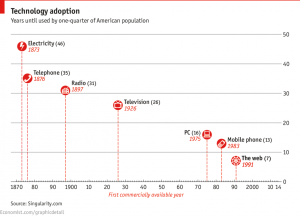

Explaining the pace-of-technological change in the U.S. through this tech adoption diagram appearing in the Economist in May 2014, Dr. Topol says Moore’s Law (in short: that computer power doubles every two years, or faster) can transform healthcare delivery through the smartphone — a fairly inexpensive platform technology that can democratize digital medicine the world over. That’s the basis for the tagline of the book — “the future of medicine is in your hands.” As these handheld minicomputers enable people do more activities of daily living, health care will be one of those.

Explaining the pace-of-technological change in the U.S. through this tech adoption diagram appearing in the Economist in May 2014, Dr. Topol says Moore’s Law (in short: that computer power doubles every two years, or faster) can transform healthcare delivery through the smartphone — a fairly inexpensive platform technology that can democratize digital medicine the world over. That’s the basis for the tagline of the book — “the future of medicine is in your hands.” As these handheld minicomputers enable people do more activities of daily living, health care will be one of those.

Dr. Topol’s vision for tech-enabled democratized healthcare is codified in the second section of his book, “The New Data and Information,” discussing “My GIS,” “My Lab Tests and Scans,” “My Records and Meds,” “My Costs,” and “My (Smartphone) Doctor.” That’s a whole lot of “me” and health engagement, where people are seen to take on major self-care roles, calling out people like Nick Dawson who leads the Society for Participatory Medicine (on whose board I sit as an advisor) who uses Evernote for his electronic health record, Dr. Cheryl Bettigole who looked into the $1,000 Pap smear, and, Angelina Jolie as health care advocate and uber-patient. Dr. Topol rightly notes there hasn’t been one big rallying cry of a public figure getting patients onto this vision…yet. Patients, companies, employers, doctors, government, data scientists all are the gravitational forces, Dr. Topol says, that will coalesce toward the inevitable future migration from “autocratic to semi-autonomous” (that is, consumer-democratized) medicine: it’s just a matter of time.

Dr. Robert Wachter’s book’s tagline is “hope, hype, and harm at the dawn of medicine’s computer age,” so you know you are entering a more sobering analysis on the role of digital in healthcare. “Healthcare’s path to computerization has been strewn with land mines, large and small. Medicine, our most intimately human profession, is being dehumanized by the entry of the computer into the exam room….Patients are now in the loop…yet they remain woefully unprepared to handle their hard-fought empowerment,” Dr. Wachter observes.

Dr. Robert Wachter’s book’s tagline is “hope, hype, and harm at the dawn of medicine’s computer age,” so you know you are entering a more sobering analysis on the role of digital in healthcare. “Healthcare’s path to computerization has been strewn with land mines, large and small. Medicine, our most intimately human profession, is being dehumanized by the entry of the computer into the exam room….Patients are now in the loop…yet they remain woefully unprepared to handle their hard-fought empowerment,” Dr. Wachter observes.

Dr. Wachter, a pioneer in the hospitalist movement, deals with patients daily at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center. In The Digital Doctor, he unveils the hard slog of sorting out the issues of the data tsunami created by sensors and patient-generated data, the cultural challenges physicians faced with cyberchrondriacal patients who over-Google symptoms and under-analyze search results, and the very bumpy road to health data liquidity — the interoperability of electronic health systems, that is often analogized to the banking world’s ATM development, but way too over-simplified. (Trust me, Dr. Wachter knows what he’s talking about: I’m married to a banker who used to eyeball global financial payments as the CHIPS clearinghouse system evolved).

The color commentary throughout this book is must-reading for people keen to understand how inpatient hospital care works, driven by medical culture. Dr. Wachter takes you into the dimly lit Chest Reading Room at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, and then explains the technology evolution in radiology from Eastman Kodak’s film to chest x-rays, CT scanning, PACS systems enabled through the DICOM standard of image communications, to today’s milieu of digital imaging. No longer does a radiologist have to be in the same building, let along the same time zone, as the patient or consulting physician. While telehealth’s benefits are many (see my papers Right Here Right Now on telehealth pioneers, and Primary Care, Everywhere, both from California HealthCare Foundation), Dr. Wachter warns, for the physician: “there is the ultimate threat: replacement by machine.” So many radiologists, seeing writing on the wall, are acting more like consulting physicians relocating back into physical reading stations in hospitals, in ICUs and ERs.

This is a crystal ball for the rest of the healthcare system, Dr. Wachter forecasts. Like Dr. Topol, he agrees that computerization in medicine will upend the lives of both doctors and patients. As Dr. Warner Slack said, “Any doctor who could be replaced by a computer should be.”

This is a crystal ball for the rest of the healthcare system, Dr. Wachter forecasts. Like Dr. Topol, he agrees that computerization in medicine will upend the lives of both doctors and patients. As Dr. Warner Slack said, “Any doctor who could be replaced by a computer should be.”

But along the way, Dr. Wachter describes the very bumpy road to getting “there,” in great detail: error-prone interfaces in electronic health records that are ill-designed; unanticipated consequences that occur with ill-timed medical alerts; and health IT regulations under HITECH Meaningful Use that compel healthcare providers to communicate with others who may have no way to receive the message (e.g., a hospital with an EHR sending a message about a discharged patient to a nursing home which doesn’t use an EHR). Quoting Dr. John Halamka, CIO of Beth Israel Deaconness Hospital, “To make me accountable for faxing when no one else has a fax machine is not exactly a great policy.”

The book’s chapter on “Epic and athena” is priceless for those of us who work in health IT. Here, Dr. Wachter highlights the dominance and business savvy of Epic Systems (described as a “closed” system), and disruptive entry of Jonathan Bush, the cofounder and CEO of athenahealth, in the Health 2.0 world (the open-system world in terms of tech). Dr. Wachter spent time with both Epic and athenahealth, and found himself “like a judge listening to two very savvy attorneys plead(ing) their case.” He concludes for now that the health care world is big enough for the two to coexist (along with many other health IT companies in the EHR space).

Although the two doctors get to patient empowerment in very different ways, ultimately, Dr. Wachter concurs with Dr. Topol: “Patients will have a much greater role, and voice, in the new healthcare system, and the technology of the future will help them manage their new responsibilities.” But Dr. Wachter’s book concludes with a necessary discussion of the nontechnical side of making health IT work, and art and science….concluding with a lovely story of a dying patient.

Mid-book, Dr. Wachter quotes Hippocrates’ Precepts: “Some patients…recover their health simply through their contentment with the goodness of the physician.”

This observation leads seamlessly into Dr. Gawande’s book, Being Mortal. The tagline to the book tells you where you’re going to go: “Medicine and What Matters in the End.” So we start at the End at the Beginning of this wonderful book in the first sentence: “I learned about a lot of things in medical school, but mortality wasn’t one of them.”

Any of us who has been part of end-stage illness for a loved one will resonate with Dr. Gawande’s first-hand stories, as he takes a patient off a ventilator, adjusts a morphine drip, and sits quietly with caregivers burning out from supporting husbands and mothers in their final days.

The central issue: advances in economic development, public health and technology enables us to live longer, many of us into old-old age. Inevitably, if we do go into old age, it’s not so very pretty for most of us. Dr. Felix Silverstone, a geriatrician for over two decades in New York, responded to Dr. Gawande’s question as to whether there’s any reproducible pathway to aging, simply responded: “No, we just fall apart.”

Dr. Gawande profiles many people and places where they age. An important lesson can be gleaned from the Chase Memorial Nursing Home, which had among its residents dogs, cats, parakeets, rabbits, and laying hens, along with indoor plants and a food and flower garden. The human residents were studied over two years, compared to people living in a nearby nursing home. The residents of Chase were prescribed half the medications as the people living in the other nursing home, and psychotropic drugs were in particular needed much less. Death rates dropped by 15% at Chase. Dr. Bill Thomas, who was medical director at the time, said, “I believe the difference in death rates can be traced to the fundamental human need for a reason to live.”

Ultimately, the real ultimately, is that “Being mortal is about the struggle to cope with the constraints of our biology, with the limits set by genes and cells and flesh and bone,” Dr. Gawande concludes. The damage we do in medicine, he says, is when clinicians don’t admit their power is finite, and always will be.

We come full circle, then, to Dr. Gawande’s raison d’etre: that the physician’s job is not to ensure health and survival, but well-being — which is about the reasons we wish to be alive, he writes. These reasons aren’t just at the end-of-life, but along our life-journeys.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I recommend that Health Populi readers read all three of these books, because together, they paint the challenging landscape we find ourselves in the midst of: technology advancement, self-care and DIY lifestyles as consumers, data abounding but not-yet-informative and empowering when we need it, and finally — living longer. Some of us are in the middle of the Sandwich Generation, caring for aging parents and young, growing children. When you’re living in the thick of this, it’s a muddle. That’s where patient and caregiver social networks (which both Dr. Wachter and Dr. Topol discuss) can be very helpful — supporting peer-to-peer health/care, and extending one’s social network which, in itself, can bolster health, wellness and day-to-day sanity.

Technology is the solution, and sometimes problem-causing. What always matters is the person in the middle — the patient, the caregiver, the consumer — and his/her life journey and informed choices throughout. Technology can help us deal with clinical issues, transparency, even democratization in the distribution of care. But the human touch of the doctor, and voice of the patient, as Hippocrates noted, can bolster life and well-being.

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the  I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a