I lost a best friend last week. His memorial service, held this past weekend, was a celebration of his life. And part of that well-lived life was a very conscious planning of his last days.

I lost a best friend last week. His memorial service, held this past weekend, was a celebration of his life. And part of that well-lived life was a very conscious planning of his last days.

The Economist published its 2015 Quality of Death Index, a data-driven treatise on palliative care, the very week my dear friend Rick died. This gives me the opportunity to discuss palliative care issues with Health Populi readers through The Economist’s lens, and then in the Hot Points below through my personal context of this remarkable man’s end-of-life choices.

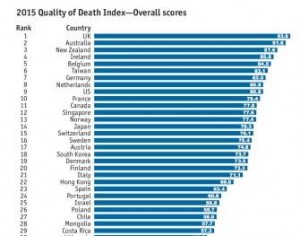

The Economist ranks 80 countries on several factors that underpin palliative care, indexed based on five factors including human resources, palliative and healthcare environment, affordability of care, quality of care, and community engagement.

As such, the “idea that there’s a bright line between disease treatment and palliative treatment is an illusion,” Diane Meier, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care told The Economist.

The US ranks in the top 10 countries for dealing with palliative care in the Quality of Death Index – a fairly high score given America’s poorer grades for other healthcare services and population health outcomes in OECD and other global surveys. Ahead of the U.S., based on this Index, we may be better off dying in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Belgium, Taiwan, Germany, and The Netherlands.

Still, the case study of the U.S. shows a nation filling in the gaps left by a fragmented healthcare payments system. These are the patients in the country with the highest healthcare spending: those with multiple co-morbidities and high burdens of chronic disease, especially people with heart failure, diabetes, stroke, and COPD. These non-communicable diseases are responsible for most healthcare spending in the U.S.

But, The Economist notes, those chronic conditions are best managed at-home, where payment currently doesn’t extend too deeply. The demands on the current U.S. home care system are huge, but Medicare incentivizes inpatient and institutional care, not cheaper, more comfortable, care at-home. Many of the gaps are filled by non-profit and private philanthropies, along with private insurers — not by government payors, who have been accused of fostering “death panel”-type behaviors.

But healthcare reforms in the Affordable Care Act, moving payment from volume-to-value, have begun the shift from more expensive care settings to lower-cost, more appropriate and more patient-satisfying sites.

For the richest nations on Earth, The Economist concludes, the challenge is moving from a culture of curing illness to managing long-term conditions and recognizing the benefits — quality of life, economic, social — of palliative care. The conclusion: “If governments are not to become negligent in meeting the needs of tens of millions of individuals and families going through what are difficult and painful experiences, a business-as-usual approach will no longer suffice.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points There is such a thing as a good death, and in the U.S., The Economist tells us that we’re inching toward that; but not quickly enough for all of America’s health citizens. Once Rick was admitted to hospital for what would be his last inpatient admission of dozens over the course of his four-year battle with multiple myeloma, his family had the option to move him back home for his very last days. You might assume that this is the choice everyone would make, but it’s all about context and what feels right for each one of us.

Health Populi’s Hot Points There is such a thing as a good death, and in the U.S., The Economist tells us that we’re inching toward that; but not quickly enough for all of America’s health citizens. Once Rick was admitted to hospital for what would be his last inpatient admission of dozens over the course of his four-year battle with multiple myeloma, his family had the option to move him back home for his very last days. You might assume that this is the choice everyone would make, but it’s all about context and what feels right for each one of us.

In this instance, it was the right choice to stay put in hospital. That’s because, with so many inpatient admissions to the cancer center, scores of staff had come to know Rick and his family. Anniversaries, birthdays, holidays, and other special moments were celebrated in the unit. Staff had gotten to know this special family so well, the place became a medical home of the best sort. Clinicians and nurses came to touch base with Rick and family and friends that had come to the academic medical center to visit Rick over the several years he was an inpatient there. Four years is a long time: I spoke with one of Rick’s nephews who began college when Rick was first admitted to hospital with multiple myeloma. This same nephew will graduate from university next spring. Time flies when you’re fighting cancer.

End-of-life care is the most personal choice we can exercise in health engagement. With late-stage diseases, there is time to plan, to consider, to sensitively and openly discuss our wishes with our loved ones.

Those of us who have used the opportunity to Engage With Grace encourage you to discuss your wishes at the Thanksgiving dinner table, after you’ve had a glass or two of wine, and the turkey’s l-tryptophan effects have kicked in. Thanksgiving is, of course the time to give thanks; it’s also the time when most U.S. families are together around a table. So when else is a better time to openly talk about your wishes to have a good death on your own terms?

Palliative care is indeed improving in the U.S., as The Economist’s data analysis illustrates. But to best cross that finish line, we must mindfully engage in discussions – with our internal selves, our families, closest friends, clergy — whichever are the right touch points for our selves. There are more choices available to you than you might be aware of.

For Rick, it wasn’t so much a finish line but a sailor’s journey via those Red Sails in the Sunset. Godspeed and peace be with you, my dearest friend and soul-brother.

You can read this inspiring man’s obit here.

And reflect on one of the wonderful self-curated songs Rick wanted sung at his memorial, The Storm is Passing Over…

Now soon we shall reach the distant shining shore,

Then free from all the storms, we’ll rest forevermore.

And safe within the veil, we’ll furl the riven sail,

And the storm will all be over, Hallelujah!

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for