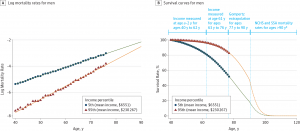

The statistics on the health of people living in America illustrate a divide between have’s and have-not’s. Average life expectancy is lower in the US compared with other wealthy nations: the wealthiest Americans live 10 to 15 years longer than the poorest, according to a landmark article in JAMA from 2016 studying the relationship between income inequality and mortality. See the first chart: this illustrates that people living in the US whose income reaches the top 95th percentile far outlive folks in the bottom 5th percentile of income.

I find myself in London, England, this week, across the Pond (that is, the Atlantic Ocean). It is useful to travel, as Thomas Jefferson wrote, noting that travel can make us wiser if indeed sadder. A Pond’s-length view from American health care can give one some sobering perspective, as I read this week’s Lancet, the British medical journal. Lancet’s April 8th 2017 edition features a special, if well-timed, series of articles titled the United States of Health. The statistic quoted above is featured in an editorial penned by Senator Bernie Sanders as an introduction to Lancet’s theme, America: Equity and Equality in Health.

The Lancet has published this series for 3 years, and notes that in this period, “health in the USA has changed and not for the better.” There is consensus, the editors recognize, that the financing of the American health-care system has become precarious, leaving people behind.

The Lancet has published this series for 3 years, and notes that in this period, “health in the USA has changed and not for the better.” There is consensus, the editors recognize, that the financing of the American health-care system has become precarious, leaving people behind.

A nine-page piece on inequality and the health-care system in the USA cites dozens of data points, culminating in some key takeaways: that,

- Economic inequality in the USA has been increasing for decades, now the highest among developed countries

- Differences in life expectancy have widened, with the wealthiest people living at least 10 years longer than the poorest

- Despite the ACA, some 27 million people in the US are still uninsured, with the potential to increase in the short-run depending on the details of health reforms that could be enacted in the coming months

- Both overall and government health spending are higher in the US than in other countries, with high cost sharing relative to other countries

- Poor and middle-class people in America spend a larger share of their incomes for care than affluent people (what we health economists could consider a regressive tax for health care)

- Rising insurance premiums for employer-sponsored plans have eroded wage gains for middle-class Americans (an issue I have frequently discussed here in Health Populi)

- Medical indebtedness is common among both insured and uninsured people in the US, often leading to bankruptcy.

These factors combined have led to a situation where the uninsured and under-insured have been much more likely to self-ration health care due to costs: to skip recommended medical tests, to postpone visits to doctors when necessary, and to avoid filling prescriptions for medicines or split pills to (presumably) extend the supply of that drug over more time.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: When it comes to health care, income disparities in the US are part of a larger ecosystem of factors that drive health disparities. These challenges include access to healthy food, education, safe environments for walking and taking exercise, and employment, among other determinants of health. In this era of genomics and digital health innovations, it’s important to realize that in America, zip code can be much more predictive of health than an individual’s genetic code.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: When it comes to health care, income disparities in the US are part of a larger ecosystem of factors that drive health disparities. These challenges include access to healthy food, education, safe environments for walking and taking exercise, and employment, among other determinants of health. In this era of genomics and digital health innovations, it’s important to realize that in America, zip code can be much more predictive of health than an individual’s genetic code.

In this Judeo-Christian week with Passover and Easter converging, I will be spending some of the holiday period in Italy and studying the role of local food in health. So it’s appropriate for me, traveling tomorrow from London to Florence, to look for inspiration from Pope Francis. “To follow the commandment ‘thou shalt not kill’ we must also say ‘thou salat not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality. Such an economy kills,” the Pope wrote in his 2013 manifesto, Evangelii Gaudium.

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on  I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,