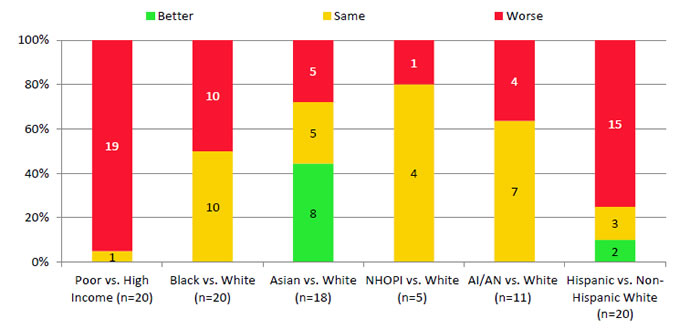

In 2015, poor and low-income people in America had worse health care than high-income households; care for nearly half of the middle-class was also worse than for wealthier families.

Welcome to the 2016 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The report assesses many measures quantifying peoples’ access to health care, such as uninsurance rates (which improved between 2010 and 2016), and quality of health care — including person-centered care, patient safety, healthy living, effective treatment, care coordination, and care affordability.

While some disparities lessened between 2000 and 2015, disparities persist for poor and uninsured people: 80% of the health disparity measures did not significantly change over the 15 years for any racial and ethnic groups vis-à-vis whites. For uninsured people, two-thirds of the measures were lower than for privately-insured Americans.

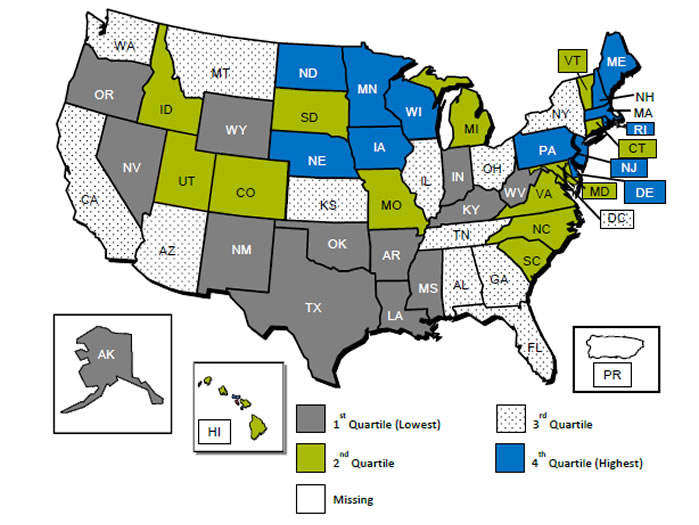

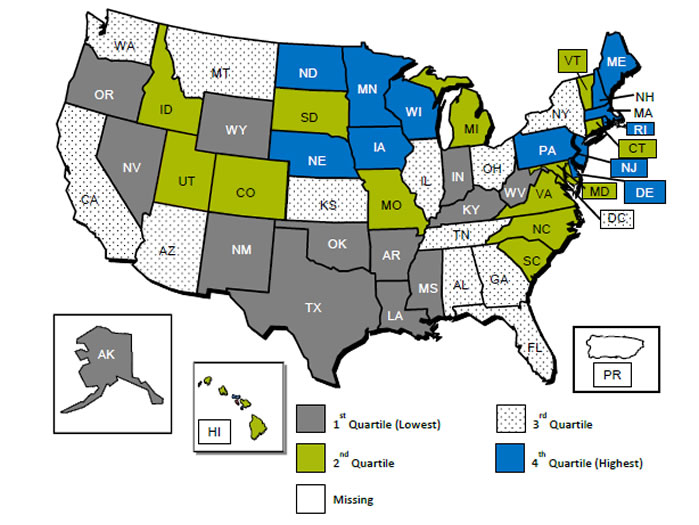

States in the Midwest and Northeast tend to have lower levels of healthcare disparities compared with the Central South, Southwest, and parts of the west — notably, Arizona and California.

Three key measures that did not improve were:

- Adults who needed immediate care for an illness, injury or condition in the last 12 months who sometimes or never got care when needed

- People unable to get or delayed in getting a needed prescription medicine in the last 12 months

- People with a usual primary care provider.

The major gain noted by the study was the growth in health-insured people — especially among Hispanics, American Indians and Alaska Natives, and Blacks, versus Whites.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Geography is healthcare disparity destiny in the U.S., illustrated in the map. This shows the overall health care quality and disparity score of each state based on the measures AHRQ studied for the report.

One specific quality component stood out for me in reviewing the data details: trends in effective treatment, which quantify timely treatment of acute illness and injury and management of chronic disease which can positively — or negatively — impact mortality, morbidity and quality of life.

While one-half of measures improved, several areas had not statistically significant changes: namely, diabetes care, treatment for illicit drug use, and treatment of alcohol problems for people age 12 and over who needed that treatment.

The two American public health epidemics of diabetes and opioid addiction are the poster children for this data point.

Another stand-out is trends in care affordability: while the growing health insured population is a positive development, high premiums and out-of-pocket (OOP) payments can deter people from accessing healthcare services. AHRQ found that 70% of the care affordability measures did not statistically improve, such as the percent of people under 65 years of age whose family’s health insurance premiums and OOP spending exceeded 10% of family income. This measure is particularly burdensome for lower-income people, who had a greater likelihood to delay needed medical care due to financial or insurance reasons. (Here at THINK-Health and the Health Populi blog, we look at that phenomenon as self-rationing by patient due to cost).

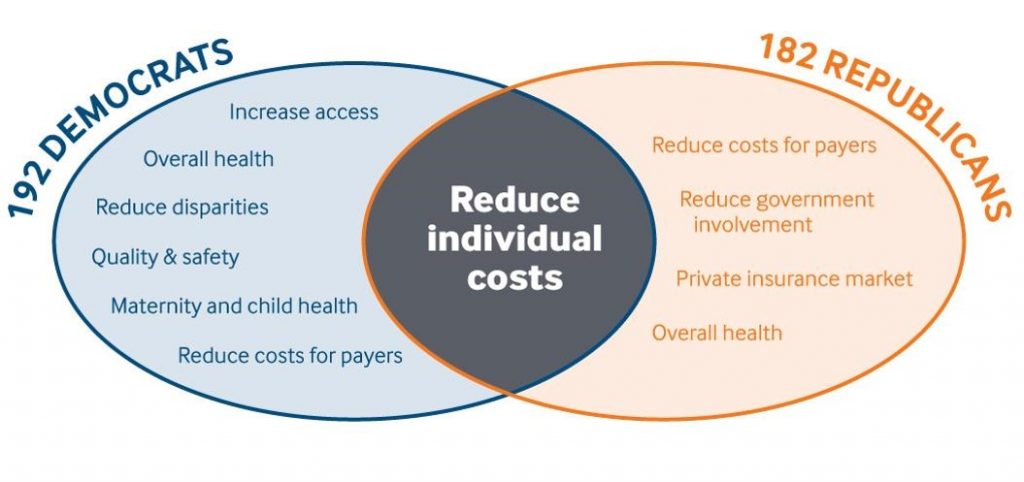

The first “A” in “Affordable Care Act” also persists for virtually all health citizens in the U.S. As the U.S. Congress soon re-convenes in Washington, DC, they have the opportunity to address the stability of health insurance exchanges as a start to helping make healthcare more affordable for the mass market of Americans. An important essay sponsored by the Commonwealth Fund was published last week in the American Journal of Public Health, calling for bipartisan health reform. The bottom-line is that reducing costs for individuals and payers is a shared priority for both Republicans and Democrats, above all other healthcare reform priorities.

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on  I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,