America’s agricultural roots go deep, from the native Patuxet tribe that shared maize with Mayflower settling Pilgrims in southern New England, to biodynamic and organic winemakers in Sonoma County, California, operating today.

In 2016, 21.4 million full- and part-time jobs were related to agriculture and food sectors, about 11% of total U.S. employment.

Farming is an integral part of a nation’s food system, so the Union of Concerned Scientists developed the 50-State Food System Scorecard to gauge the state of farming and food in the U.S. on several dimensions: diet and health outcomes, farming as an industry and economic engine, and social determinants, along with seven other categories. I’ll focus on these three elements in this post, but if you’re keen to know more about the state of farm-to-fork food, check out the Scorecard website to explore other maps.

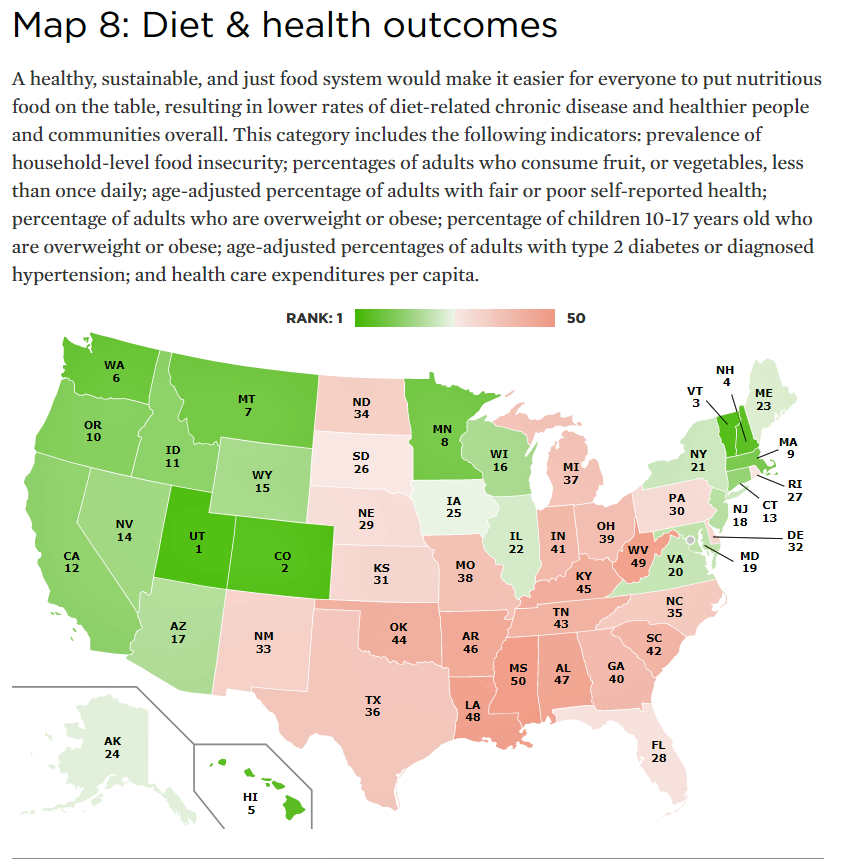

The primary utility of a food system is to nourish a citizenry: access to, and consumption of, nutritious food is a key determinant of a nation’s health and well-being.

The first map (labeled “Map 8”) illustrates the ranking by state of diet and health outcomes based on several measures: prevalence of household food insecurity, percent of adults who consume fruit or vegetables, less than once a day, percent of adults with fair or poor health, level of overweight and obesity for adults and kids, level of adults with Type 2 diabetes, and health care spending per person.

The first map (labeled “Map 8”) illustrates the ranking by state of diet and health outcomes based on several measures: prevalence of household food insecurity, percent of adults who consume fruit or vegetables, less than once a day, percent of adults with fair or poor health, level of overweight and obesity for adults and kids, level of adults with Type 2 diabetes, and health care spending per person.

The “green” states are those that rank higher for health, and the orange are those that rank low. This map echoes what others have done, featured here in previous posts on Health Populi. While many of the states in the southern U.S. have significant agricultural interests, the other factors outweigh these regions’ ability to get healthy food to the tables of citizens, as well as health citizens’ not consuming those foods in their daily diets. An example is Arkansas, home to Walmart in Bentonville; the state ranked in the top 10 for farming industry metrics, but #46 in diet and health outcomes.

The UCS invested in the Scorecard project, in part, to educate Americans on how food and nutrition bolster the nation’s health in the context of how to build sound Federal farm policy that bakes in health for people in the U.S.

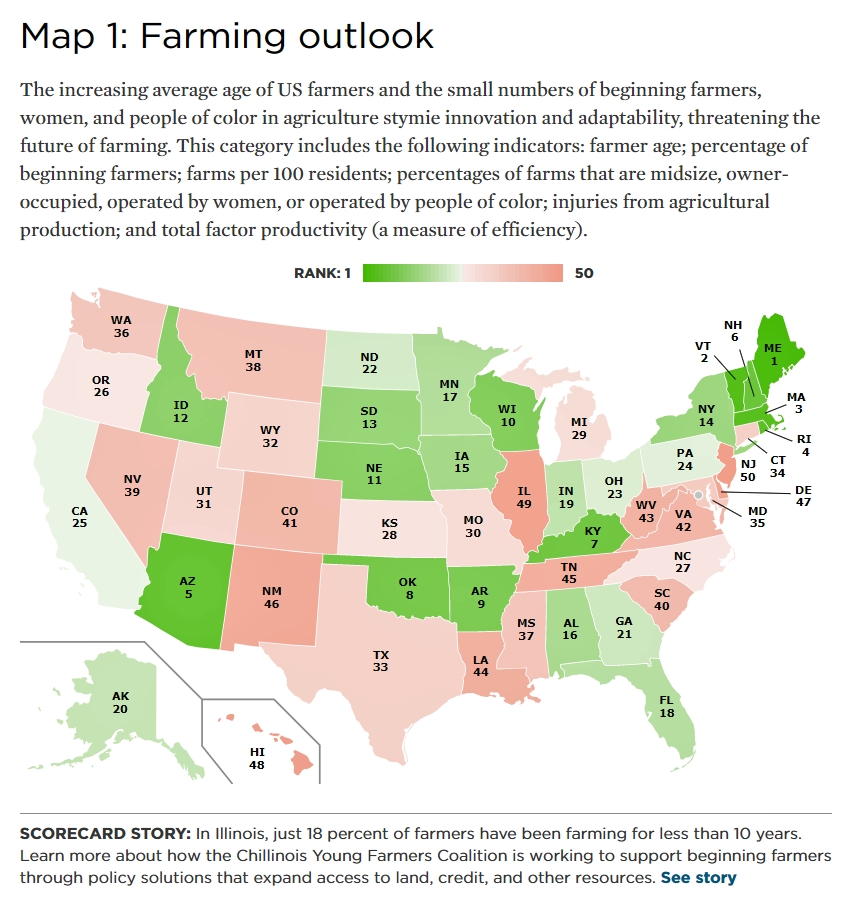

In addition to diet and health outcomes, the Scorecard measures the farming industry outlook, shown in the second map (labeled “Map 1”). This map differs from the health map, where the deep south and upper Midwest rank relatively higher for the farming outlook than the west coast. This index is calculated based on the age of farmers, percent of “beginning” farmers, farms per 100 residents, farms operated by women and people of color, injuries resulting from agricultural production, and total factor productivity/efficiency.

The Scorecard report points out a success story that has some role models and lessons in the Chillinois Young Farmers Coalition in Illinois. Chillinois welcomes a diversity membership to its ranks: young farmers, old farmers, mid-career-change farmers, teachers, web designers, documentary filmmakers, bakers, urban planners, gardeners…an ecosystem of people passionate about the land, local food, and their community.

Based on UCS’s analysis of the ten factors in their research, they recommended several policy prescriptions to inspire innovation and to improve food systems across America; first, that Congress should increase federal farm and food investments through a five-year Federal Farm Bill so that every one of the 50 States can build healthier, more sustainable food systems. Details would include:

- Training for new farmers and ranchers

- Incentives for farmers to adopt sustainable growing practices

- Funding innovative research in agriculture

- Expanding markets for farmers to sell their products

- Expanding access for affordable, nutritious food

- Ensuring food security for people who lack that access.

Another important policy that embeds health for the nation would be for States and local governments to identify opportunities to use agriculture, education, transportation, tax, and zoning approaches that would bake health into the policies. In so doing, regions would enhance public health, stronger local economies, and more resilient ecosystems.

Finally, land-grant universities in each state could support more research into local food systems and transparency to inform policymakers in designing better programs for food in relation to health, economic development, and sustainability.

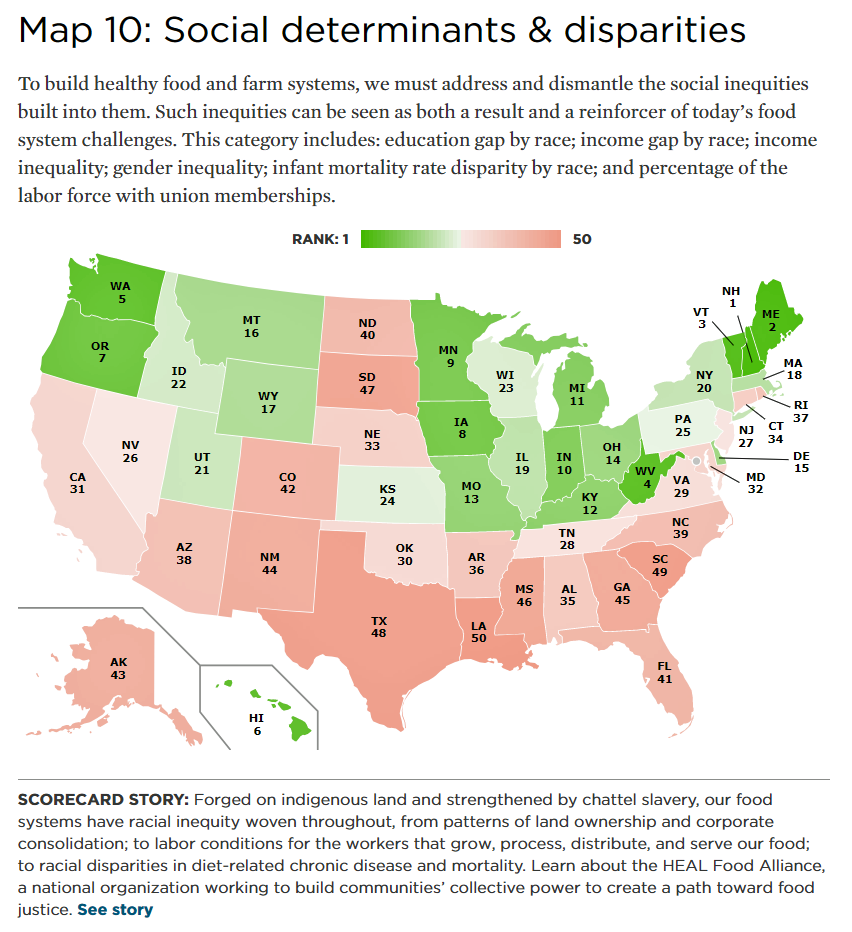

Health Populi’s Hot Points: A third indicator the UCS identified was social determinants and disparities, examining the inequities built into public policies that result in education gaps, income gaps, income inequality, gender inequality, infant mortality rate disparities, and percent of the labor force that is unionized.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: A third indicator the UCS identified was social determinants and disparities, examining the inequities built into public policies that result in education gaps, income gaps, income inequality, gender inequality, infant mortality rate disparities, and percent of the labor force that is unionized.

The third map (labelled “Map 10”) shows the ranking, with a rough cut between north and south. This map has more similarities with the diet-and-health map, perhaps because social determinants of health like education, quality jobs with health insurance, health care access, and nutritious food access work together to make a healthy community.

I was disheartened this week to learn that some SNAP clients may lose access to benefits received by shopping at farmers markets. For several years, I’ve lauded the efforts of organizations like Wholesome Wave and the Fair Food Network, among others, for channeling fresh grown food from farmers to people enrolled in SNAP benefit programs. These programs have enabled SNAP clients to double their dollars in purchasing green and fresh farmer’s market foodstuffs, magically turning $10 into $20 in good food purchases that can help people bring nutrition to their families’ kitchen tables.

This week, the Novo Dia Group, based in Austin, announced that it would stop its service in processing about 40% of SNAP transactions at farmers markets (working with over 1,700 farmers and farmer’s markets). These programs are often available in food deserts in both rural areas and cities where local residents have no other access to fresh, nutritious food options.

Novo Dia’s move results from the USDA choosing a new vendor to process payments.

Novo Dia had sunk investments into building the payments platform to serve farmers markets, and specifically the SNAP benefit system. People with SNAP benefits use an EBT card that could be processed on the Novo Dia system. Today, over 2,500 farmer’s markets use card readers via mobile phones or tablets, over which the Novo Dia software can run.

It’s a long detailed story involving regulation and technology: suffice it to say, Novo Dia was already operating on a very thin profit margin from this program, due to the level of micropayments involved in the process. With the USDA picking a new electronic payment vendor, First Data, Novo Dia announced its decision to withdraw from the program as of July 31, 2018.

The transition to First Data, along with new equipment program vendor Financial Transaction Management (FTM), will cause at least a six-month delay in moving new equipment to the markets. Suffice it to say this transition will now keep farmer’s market foodstuffs out of the hands of some SNAP beneficiaries from 1st August through the rest of the 2018 growing season.

It is important to note that the farmer’s market-plus-SNAP program has appealed to both progressive policymakers and advocates who support food-for-health, as well as conservatives who favor market-based incentives to benefit farmers and nudge consumers to healthier food choices, the Washington Post reported. The USDA’s FINI program helped to reduce food insecurity, and met with such bipartisan political approval that both the House and Senate versions of the Farm Bill more than doubled funding for FINI.

It is important to note that the farmer’s market-plus-SNAP program has appealed to both progressive policymakers and advocates who support food-for-health, as well as conservatives who favor market-based incentives to benefit farmers and nudge consumers to healthier food choices, the Washington Post reported. The USDA’s FINI program helped to reduce food insecurity, and met with such bipartisan political approval that both the House and Senate versions of the Farm Bill more than doubled funding for FINI.

This story illustrates the complexity of politics and the food system in America today, coupled with the underlying technology that enabled this successful program to work. There’s a last mile when it comes to food, and it’s how to get nutrition onto peoples’ tables. In the case of the USDA, SNAP and farmer’s markets, one technology choice will have ripple effects on a program that both Democrats and Republicans have seen valuable. But most especially, the families who have benefited, health-wise and economically, from access to good food. And that benefits all Americans for public health and well-being.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for