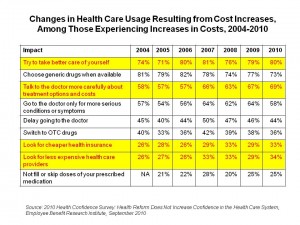

4 in 5 U.S. health citizens are trying to take better care of ourselves in light of increasing health care costs. A growing number of people are also talking with doctors about treatment options and costs, and searching for cheaper health insurance and less expensive providers. One-quarter of people didn’t fill or skipped doses of prescribed medications in response to increased costs, the same proportion as in 2009.

4 in 5 U.S. health citizens are trying to take better care of ourselves in light of increasing health care costs. A growing number of people are also talking with doctors about treatment options and costs, and searching for cheaper health insurance and less expensive providers. One-quarter of people didn’t fill or skipped doses of prescribed medications in response to increased costs, the same proportion as in 2009.

The 2010 Health Confidence Survey from EBRI shows an eroding sense of faith in the American health system, with people expecting challenges for accessing health services and paying for health care in the future. Thus, the study’s tagline: “Health Reform Does Not Increase Confidence in the Health Care System.” 12% of Americans weren’t confident that they would be able to get needed treatments in 2002; in 2010, that percentage increased to 18% of people, while confidence in peoples’ ability to get treatments stayed flat at 55% from 2002-2010.

A complementary finding to the Confidence Survey is that Americans are funding health care today to the detriment of tomorrow’s retirement savings. Specifically, Americans decreased contributions to their retirement plans (e.g., 401(k), 403(b), 457, or IRA) between 2004-2010: in 2010, 31% of people decreased their retirement savings contributions, and 55% decreased other savings contributions.

Adding to yesterday’s news that the level of uninsured and poverty dramatically increased in 2010, EBRI found that 28% of people say they have difficulty in paying for basic necessities like food, heat and housing: this increased from 18% of people in 2004, to 28% in 2010.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Peoples’ dissatisfaction with the U.S. health system is largely driven by cost. Confidence in the system is also eroding based on peoples’ perceptions of their security with employer-based health benefits. Only 1 in 2 people are confident that their insurance at their jobs will be available to them in the future, a drop from 59% just one year ago, and from 68% in 2000.

When costs increase to a health consumer, she responds in kind in some way, demonstrating that there is some elasticity in demand for health care. People substitute and adapt to new health behaviors in the face of increasing health costs. EBRI points out that it’s unclear how these changed behaviors will impact outcomes and costs in the long run: delaying care, splitting pills, inevitably, though, could result in more trips to the ER, later diagnoses for diseases such as cancer, and complications that all drive costs up.

I'm gobsmackingly happy to see my research cited in a new, landmark book from the National Academy of Medicine on

I'm gobsmackingly happy to see my research cited in a new, landmark book from the National Academy of Medicine on

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast