Looking at this photo of the 2020 Democratic Party Presidential candidate debater line-up might give you a déjà vu feeling, a repeat of the night-before debate. But this was Round 2 of the debate, with ten more White House aspirants sharing views — sometimes sparring — on issues of immigration, economic justice, climate change, and once again health care playing a starring role from the start of the two-hour event.

The line-up from left to write included:

The line-up from left to write included:

Marianne Williamson. author and spiritual advisor

John Hickenlooper, former Governor of Colorado

Andrew Yang. tech company executive

Pete Buttigieg, Mayor of South Bend, Indiana

Joe Biden, Former Vice President

Bernie Sanders, Senator-Vermont

Kamala Harris. Senator-California

Kirsten Gillibrand, Senator-New York

Michael Bennet, Senator-Colorado

Eric Swalwell. Representative for California’s 15th U.S. Congressional District

The format of Round 2 was the same as the night before, with Lester Holt, Savannah Guthrie, and Jose Diaz-Balart leading the first hour of Q&A, and Chuck Todd and Rachel Maddow wrangling the second hour. “Wrangling” is the right description for this night, which featured candidates interrupting each other, more raised voices and passionate assertions and parrying — especially on issues related to generation and age, immigration, and a spirited dialogue between Sen. Harris and VP Biden on race, busing, and segregation — which in the larger public health context continue to have a direct impact on health equity, health disparities, and socio-economic status.

Lester Holt began with Sen. Sanders, noting his call for big new government benefits like universal health care through Medicare for All and free college tuition. Holt asked the Senator whether he expected Americans to welcome paying more taxes for these services. Sanders explained that the vast majority of people will pay significantly less for health care than they do right now. And, that education is an investment in the future of the nation and thus, we must make public colleges tuition-free and eliminate student debt by “placing a tax on Wall Street.”

Lester Holt began with Sen. Sanders, noting his call for big new government benefits like universal health care through Medicare for All and free college tuition. Holt asked the Senator whether he expected Americans to welcome paying more taxes for these services. Sanders explained that the vast majority of people will pay significantly less for health care than they do right now. And, that education is an investment in the future of the nation and thus, we must make public colleges tuition-free and eliminate student debt by “placing a tax on Wall Street.”

Guthrie turned to VP Biden, stating that Sanders is calling for a revolution. Biden talked about income inequality, immediately pivoting to the President: “Trump thinks Wall Street built America,” Biden began his response. Biden’s father said, “a job is more than a paycheck; it’s about dignity and respect…We have to make sure to return dignity to middle class” by covering health insurance and affordable health care, expanding education opportunities, and ensuring that people breath air that’s clean and -insurance =covered and must afford it. Continuing education, And ensure they can breathe clean air and drink clean water. “Trump put us in a horrible situation,” and Biden would address this fiscally by eliminating the tax cuts for the wealthy.

Senator Harris, too, mentioned government benefits like free college and Medicare for All as her health plan preference. When asked, “Do Democrats have a responsibility to explain how to pay for all of the proposals” Harris responded, “Where was that question when Republicans and Trump passed a tax bill contributing $1 trillion debt to America paid for by the middle class?” She continued that working families need to be lifted up, and that rules have been written in favor of people who have the most versus the people who work the most.

Sen. Gillibrand said this debate in the Democratic party is “confusing…[facing off] capitalism versus greed.” The things we’re trying to change, she explained, is when companies care more about profits than people, citing the “greed” of insurance and drug companies and the gun lobby. Her takeaway: “We want healthy capitalism, not corrupted capitalism.”

Sen. Bennet argued for universal health care (in a public/private system) but not for Medicare for All. “Health care is a right,” he asserted as all candidates have shared. We accomplish the goal “by finishing the work we started with Obamacare and create a public option where every American can make a choice or keep private insurance.”

Mayor Pete took a more moderate approach to education and health care policy, by not supporting free college for all nor Medicare for All. Instead, he is for “Medicare for All Who Want It,” in his words.

Andrew Yang is the only candidate talking about a guaranteed basic income of $1,000 a month for every U.S. adult 18 and over, which he terms “The Freedom Dividend.” How to pay for this $12K per year per capita? Diaz-Balart asked. Yang, a technology entrepreneur, said that it’s difficult to fund “when Amazon pays no taxes and drives businesses out of stores.” Yang imagines a “trickle-up economy” that would circulate through regional economies. Thus, he would ensure these highly successful businesses bear their fair share of taxes, and also levy a value-added (consumption) tax.

Note that, up to this point, health care was not the explicit question, but clearly was on the front-burner for most of the ten candidates in this round of debate.

At this point, then, Holt moved the question to health care, addressing the group in a “raise your hand” question: “Who would abolish private insurance for a government run health care plan?”

Hands were raised by Sanders and Harris (who walked this back a bit today in interviews).

Gillibrand chimed in, discussing her “transition plan” to achieve Medicare for All. Gillibrand said she ran on M4A and in a 2:1 Republican district — and won. She wants to get to universal health care and initially create competition with insurers. “They have never put people over profits and I doubt they ever will. People will choose Medicare and we will (eventually) get to Medicare for All and then get to single payer” like Social Security, she forecasted.

Mayor Pete asserted that “everybody who says Medicare for All has a responsibility to explain how to get from here to there.” Buttigieg would call it “Medicare for All Who Want It,” made available on health insurance exchanges. If people are right, it will be more inclusive and efficient, and then a natural glide path to single payer, he explained. Even countries like the U.K. and Canada have some private insurance. “We can’t be relying on the tender mercies of the corporate sector,” he added. Primary care must be available to all, noting that his father who was recently quite ill was financially saved by Medicare coverage.

Biden, too, told his personal story of family health trauma and financial coverage with health insurance. He said the “quick way” to get to universal health coverage is to “build on what we did with Obamacare. Make sure everyone does have an option” by being able to buy into a Medicare-like plan. “Urgency matters – people right now are facing what my family faced,” he empathized.

Holt challenged Sanders, who “wants to scrap the private health insurance as we know it,” Holt described, saying that no state that has tried this has been successful. “If they can’t make it work,” Holt asked, how can killing private health insurance be successfully implemented in the U.S. for 330 million people nationally?

Sanders said it’s hard to believe every other country including the one “50 miles to the north” of Vermont, Canada, has figured out a way to provide health care for every man, woman and child, paying 50% of what we are paying in the U.S. He added that it’s not in the interest of health insurance or drug companies to provide quality care in a cost-effective manner. Americans pay the highest prices in the world for prescription drugs, Sanders repeated from the night-before debate, and he would lower these by half.

Marianne Williamson argued for the Federal government to be able to negotiate Rx prices with drug manufacturers. “We don’t have a health care system in the U.S. – we have a sick care system,” she noted. She went on to rhetorically ask why so many Americans have unnecessary chronic illnesses compared with other countries, answering that this has to do with environmental policy, chemicals, food supply, and other factors.

Bennet recounted his recent prostate cancer and treatment, which occurred at the same time his child had her appendix out. “Families should have choice – I think that’s what Americans want,” he attested. “Millions do not have health insurance as they make too much money to get on Medicaid.” Canada has around 35 million people, he said, and there are probably 35 million in the U.S. who could be part of the Buttigieg-described “Medicare for Those Who Want It” population.

Harris asked us to consider “how this affects real people.” She described a scenario of “any night in America, a parent sees their child with a temperature out of control” calling 911. They take their child the ER, and sit outside of the hospital looking at the sliding glass doors with their hand on their child’s forehead. They know that if they walk into those doors, they will have to deal with a $5,000 deductible.

Guthrie moved the question from health care coverage for U.S. citizens to health care for undocumented immigrants. This was another hand-raising exercise. Mayor Pete supported health coverage for undocumented immigrants, “because our country is healthier when everyone is healthier. Undocumented immigrants in South Bend pay sales taxes and property taxes,” adding that “this is not about a handout – this is an insurance program.”

Health Populi’s Hot Points — implications for health care industry stakeholders

Health Populi’s Hot Points — implications for health care industry stakeholders

Cover me…. The two over-arching issues about which most Americans, across political party, converge are for health insurance coverage and lower prescription drug costs. The January 2019 Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Poll found that 73% of Americans favored creating a national government administered health plan similar to Medicare open to anyone, but allowing people to keep coverage they had. This is consistent with most of the 20 debaters’ views — a la Mayor Pete’s “Medicare For All Who Want It” approach.

The ongoing challenge of explaining “Medicare for All” versus universal health coverage accomplished through a combined public/private plan takes more than a 240-character tweet to explain. As President Trump observed just weeks into moving into the White House, trying to usher through his promised repeal-and-replace policy, and with both a Republican majority House and Senate in the legislative branch under his leadership, “Nobody knew health care could be so complicated.”

Prescription drug costs are also in U.S. voters’ sights, whether we’re listening to EpiPen-buying parents, Hep C patients, or people managing diabetes. A Washington Post op-ed published earlier this month noted, “A caravan for insulin demonstrates how the American health-care system is failing us.”

Prescription drug costs are also in U.S. voters’ sights, whether we’re listening to EpiPen-buying parents, Hep C patients, or people managing diabetes. A Washington Post op-ed published earlier this month noted, “A caravan for insulin demonstrates how the American health-care system is failing us.”

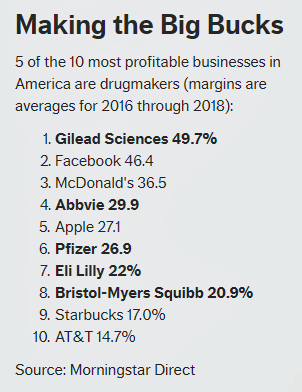

Lower my drug prices. The cover theme of the May 2019 AARP Bulletin focused on “the fight to lower prescription drug prices,” saying that, “medicine can be made more affordable. Here’s how the battle is being fought…and how it can be won.” The story included this graph comparing drug company profits to other successful businesses operating in the U.S., comparing the profitability of Gilead, Abbvie, Pfizer, Lilly and BMS to the levels of Facebook, McDonald’s, Apple, Starbucks and AT&T based on Morningstar’s data.

![]()

Across political party ID, Americans want the Federal government to negotiate prices with prescription drug companies to get lower prices for people on Medicare. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s March 2019 Health Tracking Poll found this, a policy backed by many of the Democratic Presidential candidates.

This approach is embraced by most wealthy countries around the world, which responds in part to Senator Sanders’ question about “how” other countries can fiscally provide for universal health coverage for all their health citizens.

A caveat about using traditional Medicare as “the” mechanism for covering “All” was raised by Jeff Delaney on Night 1 — that is that Medicare payments to hospitals may be insufficient to cover providers’ costs if scaled to 100% of covered Americans. We’ll need a closer actuarial analysis about hospitals’ real costs (not the “chargemaster,” but actual costs for delivering units of care) to calculate what a viable payment rate could be for these plans. And note that Medicare Advantage plans differ from traditional Medicare in providing social supports and services that many people on the plan value — and that make a difference in outcomes, health engagement, and patient satisfaction.

For more on that topic, see the May 7 2019 JAMA article, The Implications of “Medicare for All” for US Hospitals, written by two physician-influencers from Stanford University School of Medicine,

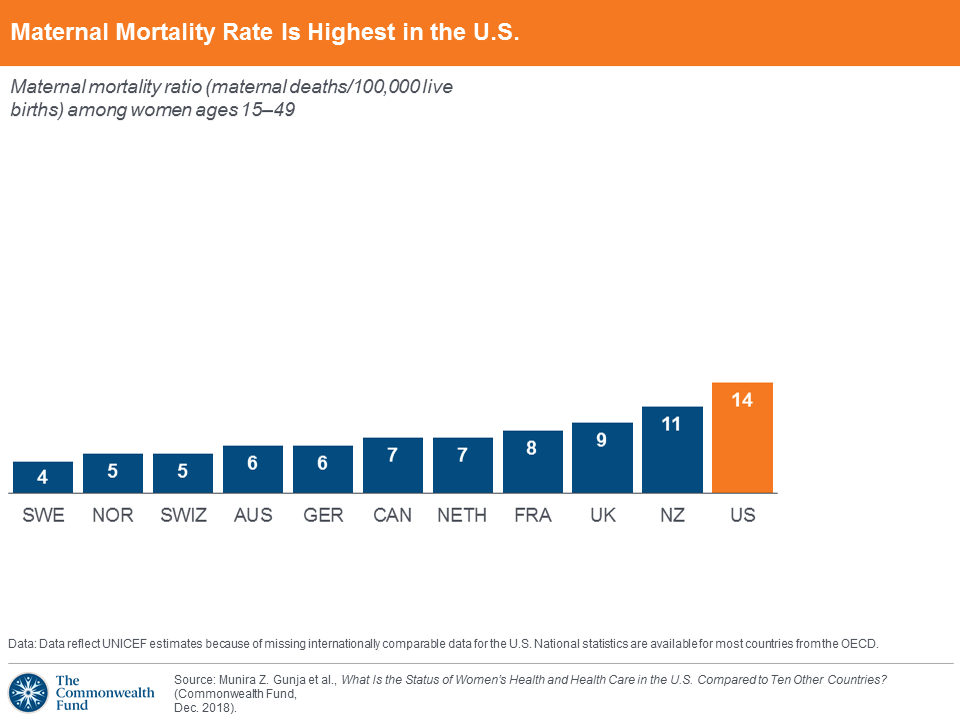

Improving health equity and outcomes – addressing and learning from the example of maternal mortality. The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate among wealthy countries. Sen. Amy Klobuchar raised this point in the first debate. I bring it to this synthesis of the two nights because too much of the health reform discussion focused on insurance without attending to social determinants of health and the direct relationship between socioeconomic status and health outcomes.

Improving health equity and outcomes – addressing and learning from the example of maternal mortality. The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate among wealthy countries. Sen. Amy Klobuchar raised this point in the first debate. I bring it to this synthesis of the two nights because too much of the health reform discussion focused on insurance without attending to social determinants of health and the direct relationship between socioeconomic status and health outcomes.

Marianne Williamson spoke to this in the very few minutes she had to speak out during the debate, and I appreciated her alluding to the opportunity to bake health into all policies — environmental, agricultural, food and nutrition, et. al.

Assuring universal health care in and of itself, whether via a M4A or public/private mix, doesn’t directly impact the many factors that shape a person’s health — those social determinants like education, clean water and air, job security, food/nutrition security, and safe neighborhoods with access to green spaces and walkability. Indeed, access to health care services is one component of the SDOH universe, but only one — impacting about 20% of health outcomes.

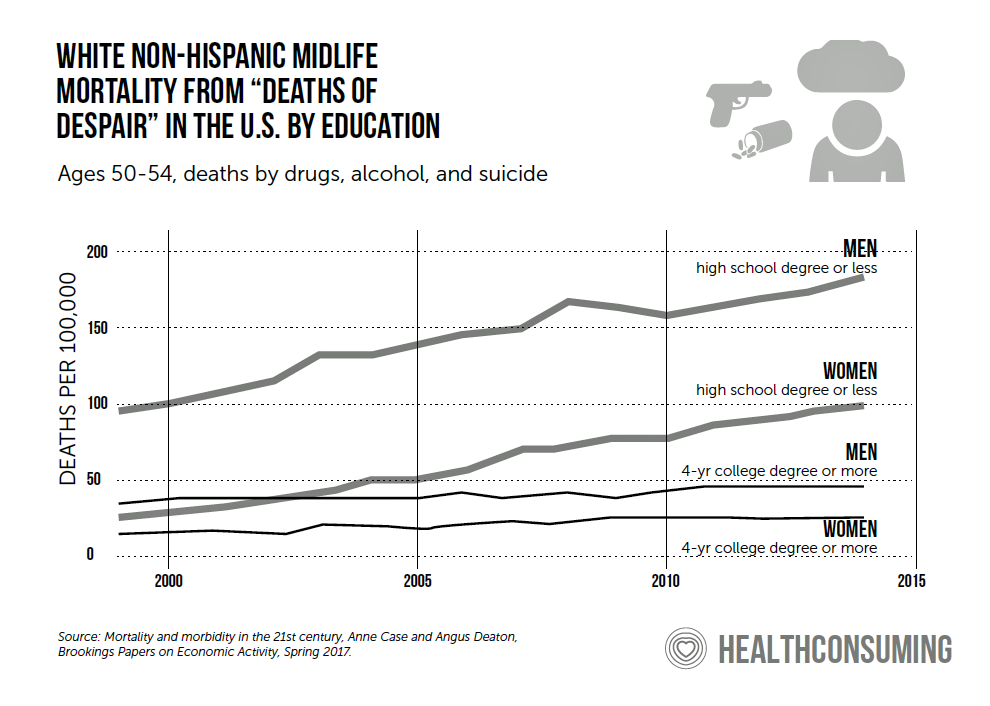

Finally…Where was the mass call-out for mental health as part of America’s public health? The rise of deaths of despair in the U.S. have reversed improvements the nation has made in life expectancy. An article this month in Rolling Stone titled All-American Despair addresses the tragic losses of lives through peoples’ stories, from everyday men to the suicides of Anthony Bourdain and Robin Williams. The author, Stephen Rodrick, took a 2,000-mile driving trip through the American West which, he hypothesized, was “a self-immolation center for middle-aged men.”

A key section of this investigative piece recounts: “For years, a comfortable excuse for the ascending suicide rate in the rural West was tied to the crushing impact of the Great Recession. But it still climbs on a decade later. ‘There was hope that OK, as the economy recovers, boy, it’s going to be nice to see that suicide rate go down,’? says Dr. Jane Pearson, a suicide expert at the National Institute of Mental Health….The impact of hard times can linger long after the stock market recovers. A sense of community can disintegrate in lean years, a deadly factor when it comes to men separating themselves from their friends and family and stepping alone into the darkness.”

A key section of this investigative piece recounts: “For years, a comfortable excuse for the ascending suicide rate in the rural West was tied to the crushing impact of the Great Recession. But it still climbs on a decade later. ‘There was hope that OK, as the economy recovers, boy, it’s going to be nice to see that suicide rate go down,’? says Dr. Jane Pearson, a suicide expert at the National Institute of Mental Health….The impact of hard times can linger long after the stock market recovers. A sense of community can disintegrate in lean years, a deadly factor when it comes to men separating themselves from their friends and family and stepping alone into the darkness.”

Mental health is part of overall health, and extracts costs out of people living in the U.S. — financial costs in terms of productivity and job security and unemployment; health care costs in terms of depression and anxiety as co-morbidities coupled with chronic conditions and acute illnesses; and finally, the loss of life described by Deaton and Case shown in this chart, along with those described by Rodrick in Rolling Stone.

Any Democrat running for President in 2020 knows that health care will drive voters to the polls the way it did in the 2018 midterm elections. Getting this right — listening to people, whether they’re rationing insulin, burying their sisters or daughters due to preventable maternal mortality, or sitting in their cars agonizing about whether to walk through the ER door with their sick child — will be key to resonating with American voters…who perhaps after the 2020 election will emerge as health citizens.

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the  I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a