The idea of health care consumerism isn’t just an American discussion, Deloitte points out in its 2019 global survey of healthcare consumers report, A consumer-centered future of health. The driving forces shaping health and health care around the world are re-shaping health care financing and delivery around the world, and especially considering the growing role of patients in self-care — in terms of financing, clinical decision making and care-flows.

With that said, Americans tend to be more healthcare-engaged than peer patients in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Singapore, and the United Kingdom, Deloitte’s poll found.

Some of the key behaviors Deloitte gauged to measure health care consumerism were,

- Increasing use of technology and willingness to share personal health information

- Interest in and use of virtual care/telehealth

- Levels of self-efficacy and prevention

- Use of tools for prescription drugs and self-care

- Interest in emerging technologies like AI and robotics.

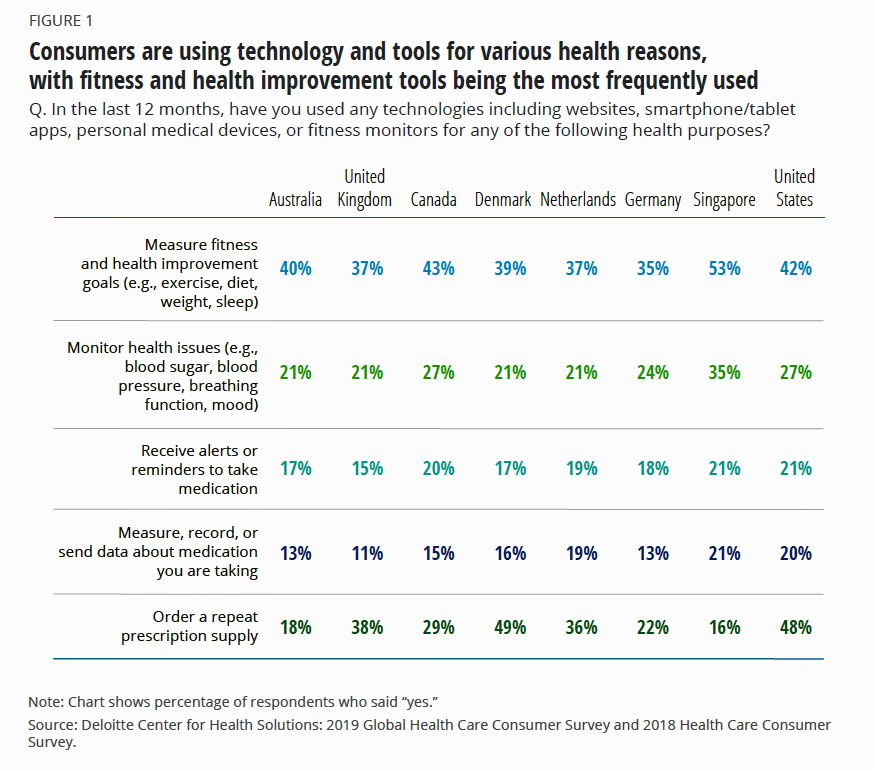

The first chart illustrates patients’ use of tech and tools for health and fitness by country studied. Across each line item, note that more Americans use these tools, with the exception of Singaporeans, more of whom use tech for health and fitness improvement, and monitoring issues like blood sugar. Danes rank with Americans on ordering repeat prescription drug supplies, and Canadians rank with Americans in a couple of categories as well.

Tracking health information doesn’t result in better outcomes in and of itself, Deloitte’s report recognizes: it takes environmental nudges, like behavioral economic strategies and public policies like healthy agricultural supports and active transportation, to move people toward healthy behaviors and sustain them.

Compared with patients living in other nations, Americans are also more likely to be willing to share their personal health data with doctors, device developers, research organizations, and emergency services. In addition, more Americans would be willing to receive alerts and share them with family members were they endangered due to a fall, rapidly elevating heart rate, or other emergency scenario.

People managing chronic conditions are also more willing than healthy consumers to share data, Deloitte found; this confirms other research on “sicker” patients’ willingness to share PHI both for their own care and research for their conditions, and to “pay it forward” for future patients diagnosed with the same illnesses.

More Americans would also be more likely to use at-home tests for genetics, blood tests connected to apps, tests for infections pre-visits to a clinician, sharing stool samples for gut microbiome testing, and apps to gauge heart health. The Americans’ comfort with these tests approach nearly one-half of people across the different test types.

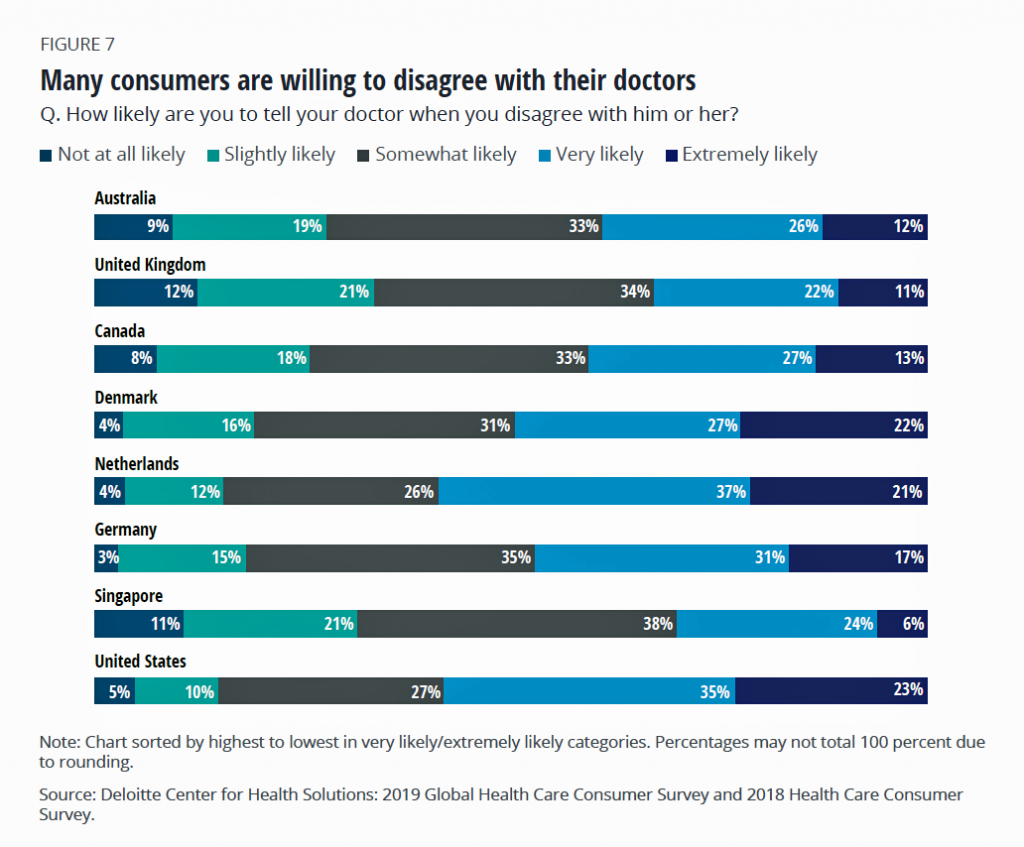

The second bar chart gauges an important metric that measures health engagement and self-efficacy — that is, whether a patient-consumer is willing to tell their doctor when they disagree with them. 68% of Americans said they would be “extremely or very likely” to tell their doctor when they disagree, tied with the same proportion of Dutch patients. Those least likely to disagree live in the UK and Singapore.

Finally, Deloitte asked consumers about their willingness-to-try emerging technologies, including surgical robots that assist surgeons in procedures, virtual clinical assistants, robots to assist caregiving, voice assistants for medication management support, and drone delivery for prescription drugs to enable a new model for “mobile pharmacy.” Detailed results for the U.S. aren’t broken out in the report, but globally, one-fourth to one-third of health citizens appear interested in these new techs to extend care beyond the office and hospital.

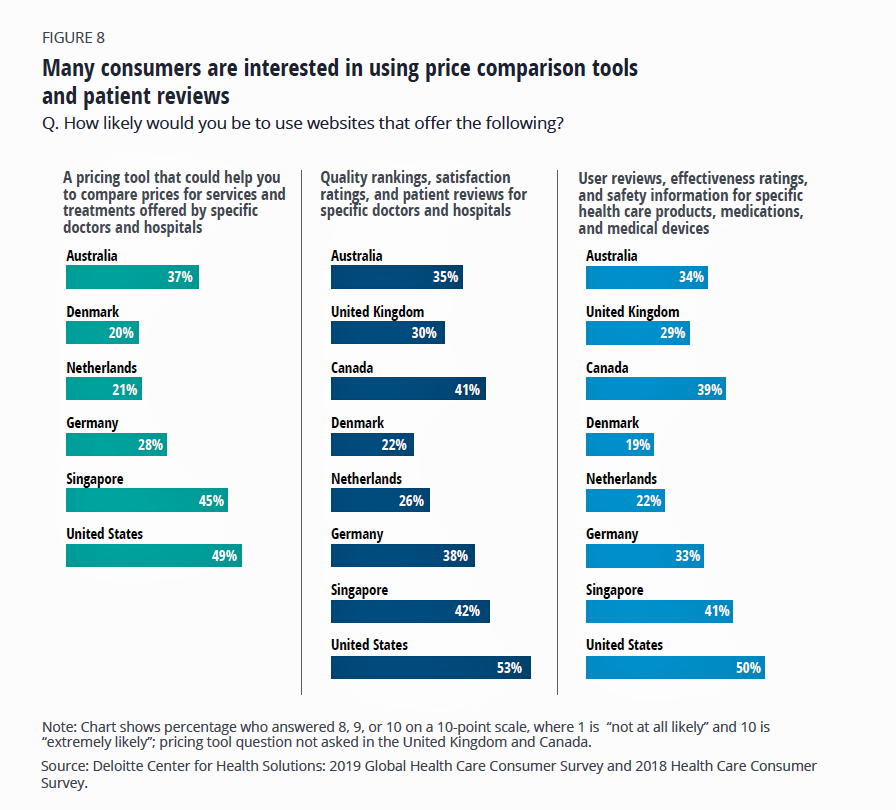

Health Populi’s Hot Points: A plurality of other nations’ health citizens would be keen to access these tools — especially, to evaluating quality and satisfaction rankings.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: A plurality of other nations’ health citizens would be keen to access these tools — especially, to evaluating quality and satisfaction rankings.

One of the unique aspects of U.S. health care is Americans’ growing financial exposure to first-dollar costs as patients continue to morph into medical bill payors. The third chart arrays health consumers’ interest in price comparison tools, and it’s no surprise that one in two U.S. patients is likely to use a website that compares prices for doctors’ and hospitals’ services, quality and patient satisfaction rankings, and user reviews for medical products and prescriptions.

A November 2019 HealthPocket survey conducted among 1,100 U.S. consumers 18-64 years of age assessed the state of medical debt in the U.S. 85% of these patients believe health care costs in general are “too high.” One-half of Americans 18-64 have avoided seeking medical care due to their lack of ability to pay for the services.

Nine in ten people told HealthPocket that prices for medical services should be as readily available as prices are on a menu at a restaurant.

Furthermore, two in 5 people said they’ve had trouble paying a medical bill, and three in 4 people said that a person’s unpaid medical bills should not affect their credit (FICO) score.

U.S. patients-as-consumers are at the vanguard of these trends, for both clinical and financial transactions.

But as the Deloitte authors rightfully pointed out, using these tools doesn’t directly result in better health status or financial wellness. In fact, health citizens in these other countries enjoy better health status and longer lives, even while spending less of their national economies on healthcare than the U.S. does.

In the case of the U.S., we’re spending a lot of development time and financial resources developing these tools and technologies. But as I write in HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen, it will take health-baked public policies and stronger privacy rights in America to bolster better personal and community health and fiscal outcomes.

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the  I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a