Americans who have commercial health insurance (say, through an employer or union) are rarely thought to face barriers to receiving health care — in particular, primary care, that front line provider and on-ramp to the health care system.

But in a new study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, commercially-insured adults were found to have visited primary care providers (PCPs) less often, and 1 in 2 had no PCP visits in one year.

![]()

In Declining Use of Primary Care Among Commercially Insured Adults in the United States, 2008-2016, the researchers analyzed data from a national sample of adult health plan members between 18 and 64 years of age and saw that visits to PCPS fell by 24.2%, from 169.5 to 134.5 visits per 100 member-years. At the same time, the percent of plan members with no PCP visits in one year increased from 38.1% to 46.4%.

The biggest fall in visits was among younger adults, people without chronic conditions, and health plan members living in lowest-income areas.

Note that “out-of-pocket cost per problem-based visit” increased by $9.40, an increase of 31.5%.

Most impressively, statistics-wise, was that visits to alternative venues like urgent care centers rose by 46.9%.

The researchers pointed to several possible drivers to lower PCP visits including perceived visit needs, financial barriers like co-payments, and use of alternative sources of care.

For context,  I re-visited a similar recent study on this topic, published in the November/December 2019 Annals of Family Medicine, looking at national trends in primary care visit use between 2008 and 2015.

I re-visited a similar recent study on this topic, published in the November/December 2019 Annals of Family Medicine, looking at national trends in primary care visit use between 2008 and 2015.

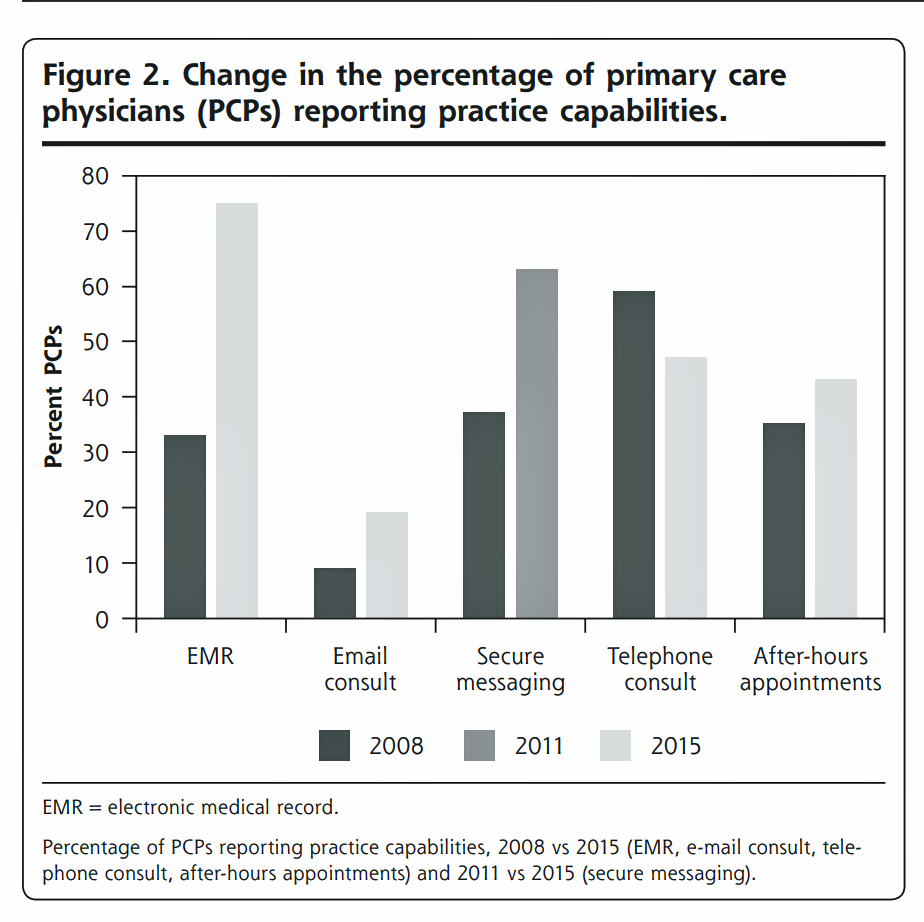

This bar chart comes from that study, which found a decline in primary are rates — but for those patients who had visits, those were longer and addressed ore issues per visit. And so I included the second study above to complement the Annals of Internal Medicine research. Note in the chart the emerging trend by 2015 of PCPs emailing with patients and offering after-hours appointments.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Here is what we know-we know about primary care: that countries with strong primary care backbones where patients lack barriers to seeking PCP care spend less money per capita on health care. And, that primary care is a social determinant of health, bolstering public and individual health. That link will take you to my blog written on primary care ROI in November 2009 – and the math holds ten+ years later.

Oh, and did I mention that life spans are longer for people who live in places with greater primary care physician supply?

But America’s per capita primary care physician supply fell between 2005 and 2015.

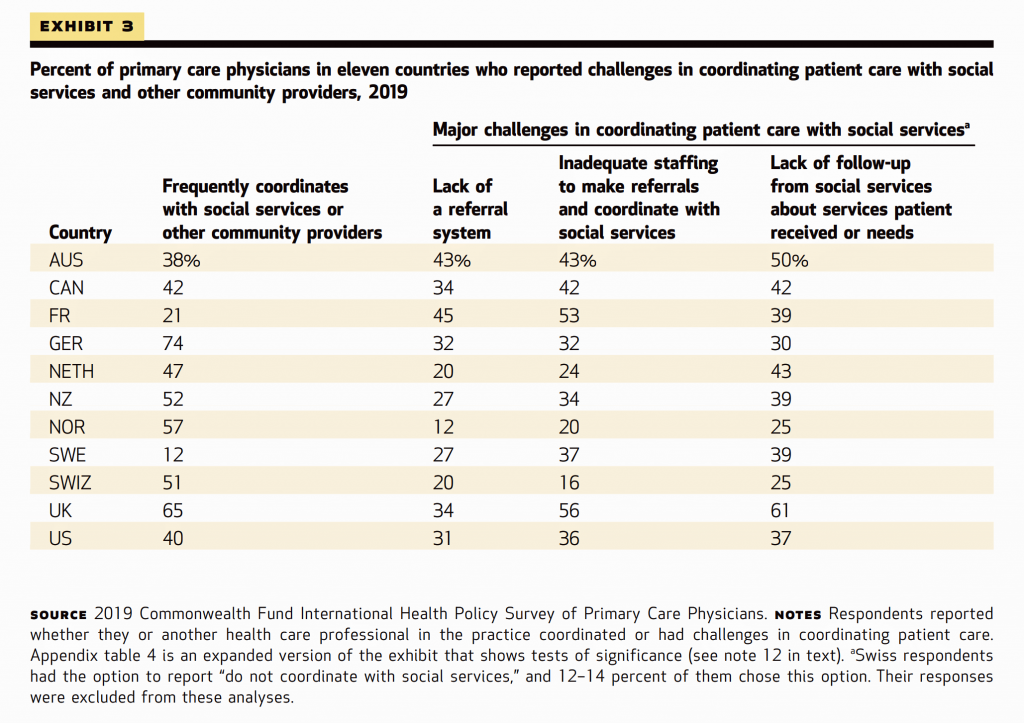

The January 2020 Health Affairs published a paper on Primary Care Physicians’ Role in Coordinating Medical and Health-Related Social Needs in Eleven Countries. Sponsored by the Commonwealth Fund, the research found that, compared with primary care doctors in other countries, a large proportion of U.S. PCPs did not coordinate patient care with specialists, other settings of care, and with social service providers.

The January 2020 Health Affairs published a paper on Primary Care Physicians’ Role in Coordinating Medical and Health-Related Social Needs in Eleven Countries. Sponsored by the Commonwealth Fund, the research found that, compared with primary care doctors in other countries, a large proportion of U.S. PCPs did not coordinate patient care with specialists, other settings of care, and with social service providers.

This third table comes from the paper, and the first column details the percent of PCPS who “frequently coordinate with social services or other community providers.” The U.S. percentage is lackluster vis-a-vis physicians in most other OECD countries.

Social determinants of health are increasingly recognized as key pillars and investments for overall health and lower costs. In the U.S., more health plans are attending to SDoH, and physicians at the front-end challenged with this coordination work-flow.

So what is primary care, anyway? The American Academy of Family Physicians offers several definitions, which I’ve mashed up here.

A primary care practice serves as the patient’s first point of entry into the health care system and as the continuing focal point for all needed health care services. Primary care includes health promotion, disease prevention, health maintenance, counseling, patient education, diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic illnesses in a variety of health care settings (e.g., office, inpatient, critical care, long-term care, home care, day care, etc.). Primary care is performed and managed by a personal physician often collaborating with other health professionals, and utilizing consultation or referral as appropriate. The structure of the primary care practice may include a team of physicians and non-physician health professionals. Primary care provides patient advocacy in the health care system to accomplish cost-effective care by coordination of health care services. Primary care promotes effective communication with patients and encourages the role of the patient as a partner in health care.

It’s important to call out the importance of primary care for any health reform plan that 2020 Presidential candidates are profferring. The Affordable Care Act sought to promote primary care in many provisions. The U.S. needs, and Americans deserve, a strong primary care backbone for physical and fiscal health. This is one of the pillars for U.S. health citizenship I include in my book, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen.

Today, so much primary care is self-care — where empowered patients, now health consumers, seek to take control over their health/care experience and shop what medical services and wellness opportunities are shoppable. Thus, the rise of alternative sites — whether “consumed” in urgent care, in retail clinics, via a HIPAA-compliant virtual visit on a smartphone, in superstores like Walmart, or at a Health Hub at a CVS brick-and-mortar store.

There’s a blur between self-care and more formal primary care. As physicians and other clinicians take on more value-based payment, reimbursement that’s partially tied to outcomes or other metrics, they’ll be motivated to keep people healthy at home and at work. So self-care will complement (and is complementing) formal primary care, whether through that patient-consumer’s use of over-the-counter meds, a telehealth visit in real-time or asynchronous email exchange, using remote health monitoring and checking outlier data, or using home health/community health workers.

This requires partnering in a re-bundled health ecosystem curated by clinicians and co-designed by patients, whose preferences must be baked into the service offerings. The growth in health consumers’ use of retail health sites is a signal patients are already shopping for health care, when they can.

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast  This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're

This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're