During the latest economic recession in the U.S., the growth in the number of the health-uninsured was greater for white people and native-born citizens than for others in the nation. At the same time, the erosion of employer-sponsored health insurance continued.

During the latest economic recession in the U.S., the growth in the number of the health-uninsured was greater for white people and native-born citizens than for others in the nation. At the same time, the erosion of employer-sponsored health insurance continued.

The 2007-09 Recession And Health Insurance Coverage, published in Health Affairs in December 2010, analyzes data from the Census Bureau focusing on “health insurance units” in the U.S.: these are defined as nuclear families in the U.S. who can be covered under one insurance policy–the policyholder and his/her family members.

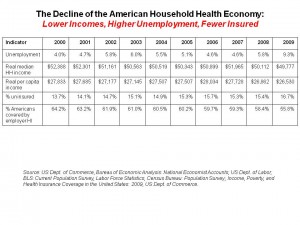

The chart incorporates data from the Health Affairs article, as well as two lines of data I entered for percentage of the U.S. uninsured, and % of Americans covered by employer health insurance over the ten-year period, 2000-2009. Over that decade, unemployment was lowest in 2000, when real median household income was highest at $52,388, uninsured population was lowest at 13.7%, and employer-based insurance was at a high of 64.2% of employers who offered workers insurance.

By 2009, all of these statistics reached their worst levels: unemployment hit 9.3% nationally, real median household income fell to $49,777, the percent of uninsured rose to 16.7%, and the proportion of U.S. covered by workplace health insurance fell to its lowest level of 55.8% – that is, from 2/3 of the U.S. population covered by employer-based health insurance in 2000 to just over 1 in 2 health citizens covered by insurance at work ten years later.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: John Holahan, a director at the Urban Institute, wrote this piece. He points out that changes in health insurance coverage followed the pattern of economic activity, as shown in the chart. The growth in Medicaid coverage did not offset the decline of workers losing their health insurance; governors have been broke as state tax receipts have declined in the recession, challenging them to balance their budgets and forcing cuts into all kinds of state-provided programs – health, education, public works and a whole host of services.

In this decline, though, whites have been more seriously affected by the economic downturn. Typically, whites have had higher incomes and have been less likely than people of other races to be uninsured. Not this time around; Holahan notes that by 2009, whites were less likely to have employer-sponsored insurance than in 2007. Furthermore, the expansion of Medicaid couldn’t absorb these newly uninsured Americans, as the uninsurance rates for whites increased by 15%, Holahan calculates. While Blacks and Hispanics have been adversely impacted by the recession, too, their income reductions were not as dramatic as those of whites in America. To further break stereotypes, most of the increase in the number of uninsured people in the U.S. was among native-born U.S. citizens.

The timing of this paper is very important as Congress looks toward 2011 and its policy agenda. If moving away from covering the uninsured becomes part of that agenda during this so-called “jobless recovery,” and continuing erosion of health insurance at the workplace continues, the percentage of uninsured Americans for 2011 and beyond will continue to grow. Holahan is right to point out that health reform, as it’s currently written, doesn’t cover large numbers of Americans until 2014. What happens in the immediate term, then, to growing numbers of uninsured adults, white, Black and Hispanic alike? Governors can’t be counted on to expand Medicaid eligibility. The impact on hospital emergency rooms as primary care safety nets, and subsequent bad-debt accruing to these hospitals, is but one easily forecastable event. Many other negative economic impacts will spill over through the economy beyond the health sector until the uninsurance rolls get closer to zero.

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast  This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're

This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're