We’ve long know that “the patient” has been an under-utilized resource in the U.S. healthcare system since Dr. Charles Safran testified with that statement to Congress way back in 2004…an era where bipartisanship for health IT was a real thing.

Today, with the insights of Alexandra Drane (Founder of ARCHANGELS) and Dr. Nirav Shah (of Stanford University), we know that caregivers are among the most over-utilized resources in the U.S. healthcare system — overused, over-stressed, under-paid, detailed n  How Health Systems Can Care for Caregivers, published in the NEJM Catalyst July 2021 issue.

How Health Systems Can Care for Caregivers, published in the NEJM Catalyst July 2021 issue.

In this study, Drane and Shah analyze the input of 386 health care executives, physicians, and clinical leaders working across provider organizations (hospitals, clinics, health systems, physician groups), assessing their perceptions of caregivers’ role with the patients they love and interactions with the health system.

Or “non-system,” as is the labyrinth and Rube Goldbergian plumbing caregivers experience when trying to care.

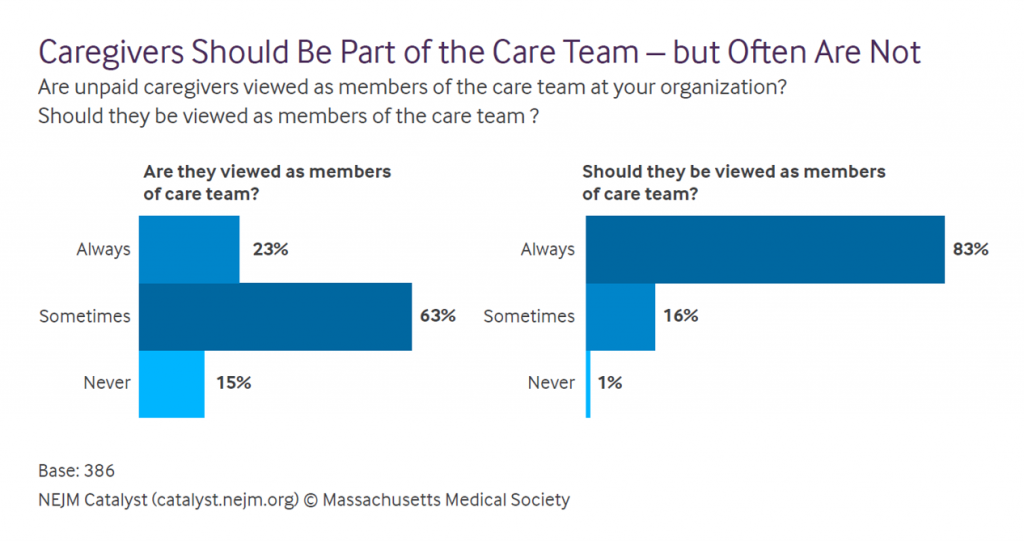

Nearly always, health execs believe, caregivers should be viewed as members of the (clinical) care team, shown on the right side of the first chart. But the left side shows the gap to which health execs admit — that, mostly, caregivers are not seen as members of the care team.

There are many benefits that accrue to health care organizations that meet caregivers’ needs: among them, improved patient clinical outcomes, improved patient and family experience, and improved treatment adherence.

The top-, bottom-, and middle-line through the caregiver role in healthcare is that, in Shah’s words,

The top-, bottom-, and middle-line through the caregiver role in healthcare is that, in Shah’s words,

“The biggest untapped opportunities for health systems administrators and clinical teams to impact the health and wellness of their patients — and to truly get to patient-centered care — is to care about unpaid caregivers.”

Why? Because the value of unpaid caregivers in the U.S> economy equates to as much as 2.5% of U.S. gross domestic product.

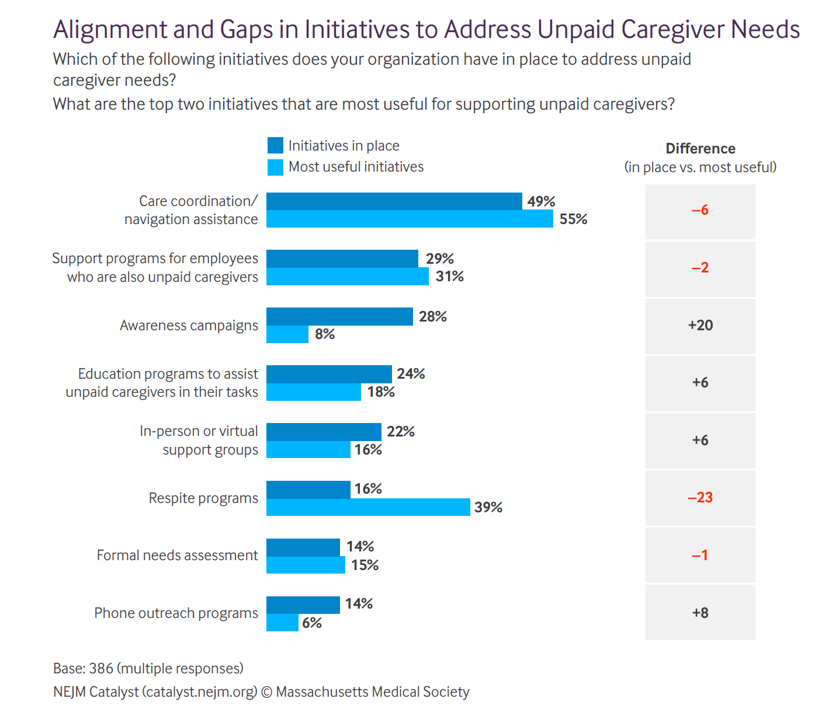

The vanguard of health care leaders has begun to recognize this value and importance delivered by unpaid caregivers. Some of those initiatives are shown in the second chart here from the NEJM Catalyst study.

The most useful strategies noted by execs are care coordination and navigation assistance (addressing that caregiver’s labyrinth of stressful experience), respite programs (giving caregivers breaks from the caring), and support programs for employees who are also unpaid caregivers (as, say, embedded into employee assistance programs, health benefits, or more holistic worker benefit programs bolstering financial and overall wellness).

One-half of leaders have care coordination/navigation programs in place. The biggest gap is for respite programs, a delta of 23 points between “need/usefulness” and “putting in place.”

Underpinning these strategies to support caregivers are a portfolio of technologies used to communicate with folks. The top tech’s used with unpaid caregivers including patient portals (for 55% of the execs studied), telehealth (among 53%), communication between providers and unpaid caregivers (with technology platform type not mentioned, such as phone call, email, or text), and seeking/scheduling in-home nurses/aids (for 31%). Remote monitoring is utilized by 1 in 5 health care leaders.

Staffing is the top barrier to addressing caregiver needs. This is a high-touch challenge as it’s currently delivered and envisioned, so 52% of leaders said insufficient staff support such as social workers is a top barrier to addressing unpaid caregiver needs. Lack of organization-wide strategic commitment, physician time limitations during the clinical encounter, and lack of standardized measures to assess caregiver needs are additional key barriers to supporting unpaid caregivers.

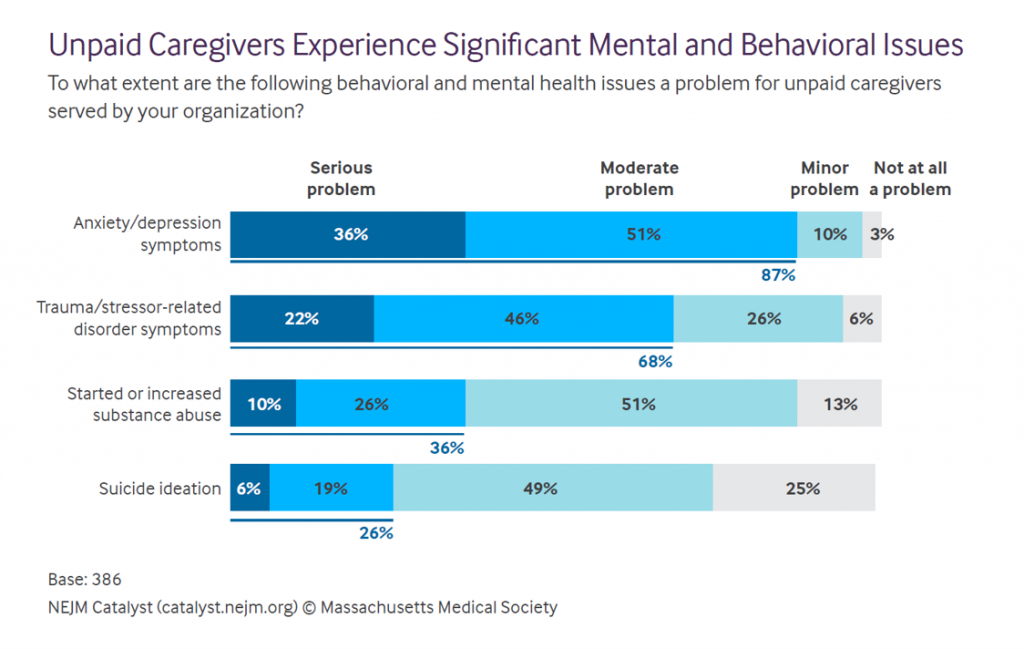

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The prevailing, universal health outcome for unpaid caregivers is eroded mental and behavioral health. This study quantified various flavors of mental un-wellness, shown in the last chart.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The prevailing, universal health outcome for unpaid caregivers is eroded mental and behavioral health. This study quantified various flavors of mental un-wellness, shown in the last chart.

Anxiety and depression symptoms are a serious problem for over one-third of unpaid caregivers, with an addition 51% of them seeing a “moderate problem.”

Net, that’s 9 in 10 caregivers admitting to anxiety and depression in their daily lives.

Then there’s trauma as a stressor, felt by two-thirds of caregivers.

Substance use increases or abuse is a problem among 36% of caregivers. And suicide ideation — a challenge for one in four unpaid caregivers.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened mental and behavioral health concerns for unpaid caregivers. We know that the public health crisis exacerbated most peoples’ state of anxiety and stress, tracked and quantified by the American Psychological Association’s ongoing Stress in America studies.

For unpaid caregivers, the COVID-19 era has worsened mental and behavioral health issues, with 60% of execs observing these have “significantly increased,” and 32% saying the challenges have “somewhat” increased.

The prescription based on Drane and Shah’s analysis here starts with health care leaders and clinicians first recognizing and calling out the caregiver’s role in their patient’s lives and medical care, ongoing; followed by support strategies that provide respite to the caregiver, ongoing communication and counsel, and baked-in services to support the caregiver’s mental and emotional health and wellbeing.

The ROI on this support can be quantified by the health system in terms of avoiding patient re-admissions to hospital, improved health outcomes that prevent unnecessary/avoidable utilization in higher cost downstream settings (i.e., hospital beds), and improving the well-being of those most at-risk for trauma, substance abuse, and suicidality — the loving caregiver who is serving up unrecognized value to the health system and the nation’s GDP.

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the

Thank you, Jared Johnson, for including me on the list of the  I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a