The COVID-19 pandemic revealed long-systemic health disparities in the U.S. and in other parts of the world. Income inequality, sickly environments in homes and communities (think unclean air and water), lack of public transportation and nutritious food deserts combine to limit peoples’ health and well-being.,

Beyond the traditional social determinants of health, such as these, we’ve called out another health risk that became crucial for life in the coronavirus pandemic era: digital connectivity,

Beyond the traditional social determinants of health, such as these, we’ve called out another health risk that became crucial for life in the coronavirus pandemic era: digital connectivity,

Indeed, WiFi and broadband represent the newest social determinant of health to add to a growing list of risk factors that challenge health citizens’ health.

Kudos to VIVE 2022, the health-tech conference convening this week in Miami, for curating an entire conference track devoted to “Techquity,” attending to the convergence of technology and equity — equity for care and digital access that helps bolster health, well-being, and community. VIVE’s techquity description appears here, challenging us to “harness tech to reflect the better angels of our nature.”

To that end, Ashish Atreja, MD, CIO and Chief Digital Health Officer with UC Davis Health, shepherded a panel at VIVE titled “Catalyzing Health Equity through Data Collaborations.” Ashish brainstormed techquity with three panelists who are walking the talk about social determinants and digital health: Dr. Lu De Souza, Chief Medical Officer with Cerner; Dr. Pierre Vigilance, VP of Population Health and Social Impact at Equideum Health; and, Theresa Demeter, Managing Director with Tegria.

Each of these four angels discussed success stories and factors that can address techquity and improve care and outcomes for all health citizens.

Pierre’s personal story well arms him for this techquity moment. Born and raised in the UK, Pierre’s mom was a social worker and father an optometrist. Pierre grew up with care provided by the National Health Service (NHS) in England, which helped shape his worldview on health equity from an early age. Growing up with the NHS and with the parents he had, showed Pierre “what it took for people to be healthy, as well as their social spend,” Pierre remarked in his personal introduction.

By 17, Pierre came to the U.S. and over the years because immersed in different organizations, ventures, and medical school, becoming clearer that “what we do (especially) in emergency medicine is not what we are supposed to be doing” he said — people should not be in the ER as their first on-ramp to care, he figured out pretty quickly in his career.

In his work at Howard University and in Baltimore in the public health department, he learned to connect families with services they needed beyond medical care, for housing, community development, education, transportation — all, in his words, “pieces of the puzzle that go into what makes people healthy.”

As VP of Pop Health and Social Impact at Equideum, Pierre is working with an organization leveraging use of blockchain and AI to improve health outcomes.

As VP of Pop Health and Social Impact at Equideum, Pierre is working with an organization leveraging use of blockchain and AI to improve health outcomes.

“Machines need diverse data to create the most generalizable information they can,” Pierre noted. “We don’t necessarily give them the food they need, a minimal diet of burgers but no chicken tikka masala,” he tastefully described, mindful of that “very hungry monster that is machine learning” requiring diverse and lots of data to do the work it needs to do.

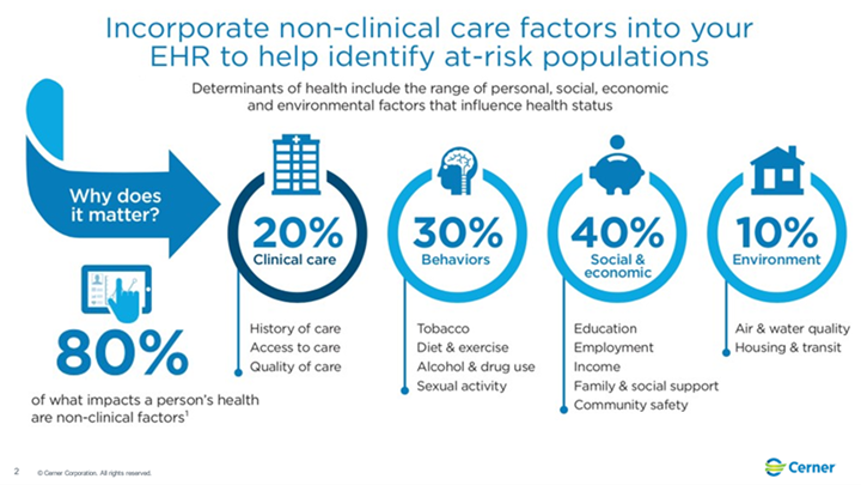

Central to that work is to reduce bias in AI algorithms, recognizing that only 20% of the data that’s useful relates to “health care” but 80% relates to health in its broadest definition — those social determinants that make up the rest of the “pot” that cooks up actionable information to benefit peoples’ health and wellbeing.

Dr. Lu De Souza, CMO of Cerner, discussed the “troves and troves of health care data that can help democratize” care and outcomes. She discussed several examples in Cerner’s client based where they have been able to liberate data to close the digital equity gap.

Dr. Lu De Souza, CMO of Cerner, discussed the “troves and troves of health care data that can help democratize” care and outcomes. She discussed several examples in Cerner’s client based where they have been able to liberate data to close the digital equity gap.

At South Carolina’s Saint Francis Health System, the provider was keen to see where African-American patients lived with higher prevalence of hypertension and uncontrolled diabetes. Using geospatial modeling and lots of data analysis via Cerner’s trove of information, the health system was able to identify a cluster around an African-American church. This inspired a partnership between the health care organization, the church, and nurses who were also part of that community. The collaboration implemented a health screening program, bringing church leaders into the process to bolster health literacy and outreach to individuals. In a short amount of time, Lu reported, the community increased control of diabetes and hypertension by 50% — a transformation change where patients stayed “in the right venue of care,” Lu asserted.

She noted with these examples that “we can’t do this alone,” where partnering in multi-stakeholder approaches improves care outcomes, health equity, and innovation.

So much benefit comes from collaboration in Big Data, Theresa Demeter of Tegria has found: “we can get there faster working together,” she believes, channeling that inspiring maxim,

So much benefit comes from collaboration in Big Data, Theresa Demeter of Tegria has found: “we can get there faster working together,” she believes, channeling that inspiring maxim,

“If you want to go fast, go alone, If you want to go faster, go together.”

One case study “going faster” through multi-stakeholder collaboration is Tegria’s work with the South East Alaska Health Consortium (SEARHC), over 27 disparate areas and communities many of which need seaplanes to get to. These are hard-to-access communities, the definition of “rural.”

The organizations in this consortium had data but they also bore the “super determinants of health” — access and health literacy challenges.

Tegria worked with the group to improve internet access where it needed to be so communities could access their own health data and reach access to virtual care and specialty care with the intent to keep patients in their own communities with their families and those who know them well….to provide the best care and understanding their social-ness.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Theresa pointed out healthcare’s long history of not inviting “everyone” to the table

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Theresa pointed out healthcare’s long history of not inviting “everyone” to the table

This can harm patients, as it did with COVID, dramatically.

“If we don’t start at a foundational level of partnering, bringing everyone to the conversation with a seat at the table,” she explained, we run a high risk of continuing to create biases and leaving people out.

Lu doubled-down on that message of inclusivity and collaboration, describing inclusion through partnership with “organizations that look like us,” and other relevant entities in peoples’ communities including but not limited to payors, community leaders, government representatives and….patients.

This is a cultural change that must begin with “humble inquiry” in Lu’s words: we must have humility in how we approach health equity. No one organization or data source can deliver an impactful solution.

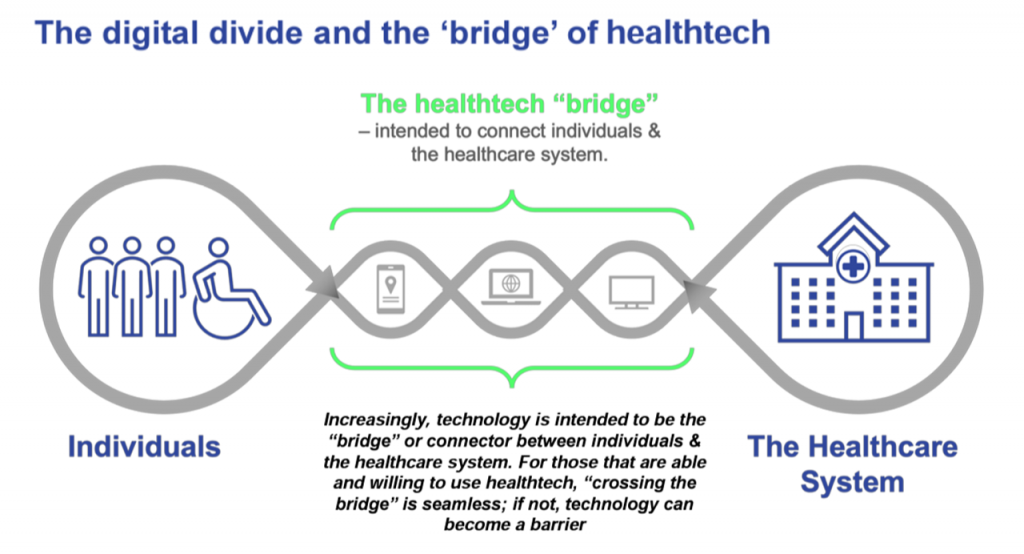

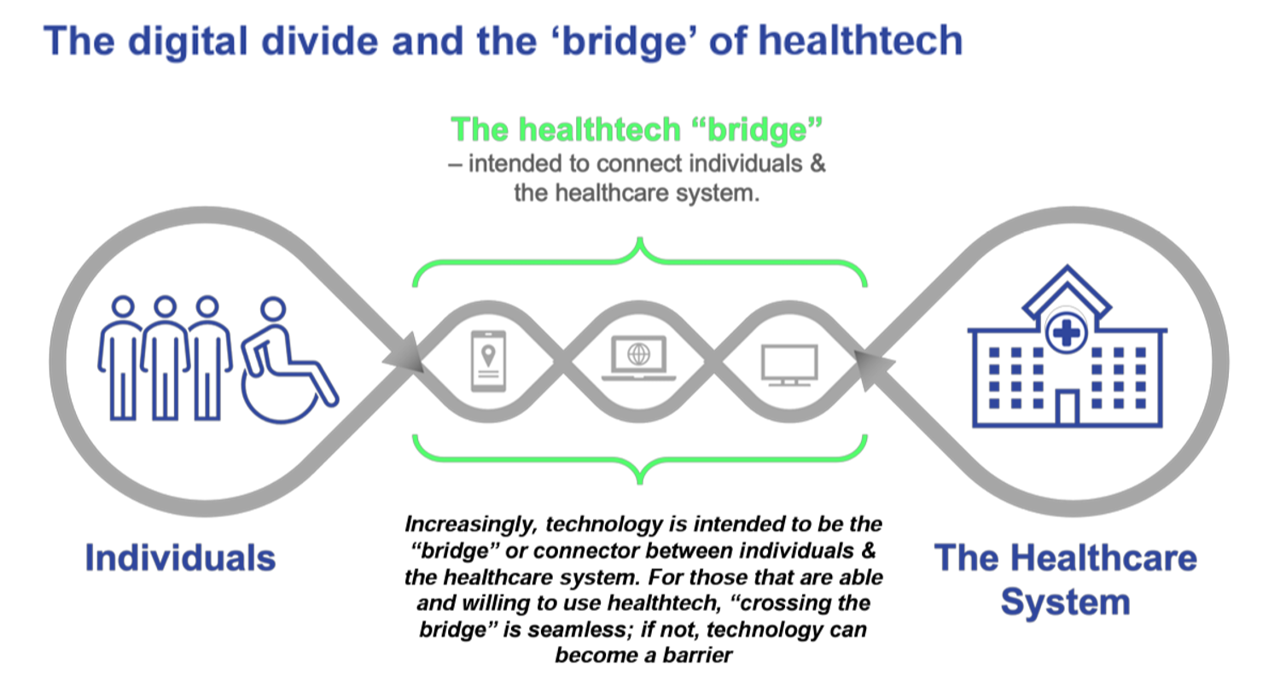

Techquity “is not (part of) a shiny object syndrome,” Ashish counseled us. His team’s mission at UC Davis Health is that no patient gets left behind. Embedded into that objective is to move from a digital divide to building a digital bridge. This concept is shown in the last diagram from a paper published this week via a collaboration between Ipsos and the HLTH Foundation (with which VIVE is an organizational family member).

Techquity “is not (part of) a shiny object syndrome,” Ashish counseled us. His team’s mission at UC Davis Health is that no patient gets left behind. Embedded into that objective is to move from a digital divide to building a digital bridge. This concept is shown in the last diagram from a paper published this week via a collaboration between Ipsos and the HLTH Foundation (with which VIVE is an organizational family member).

And that requires collaboration across diverse data and industry siloes, the kind of which we can see in Equideum Health’s partnerships diagram shown here.

Pierre said this is not just about health data: we must get beyond the “health care fiefdom,” as other organizations beyond the medical workflows provide care and services to patients.

As Ashish concluded, talking about what we would like to see a year from now on this panel:

“Next time, let’s have a patient right next to us. That would be great thing.” Indeed: patients, the last and most important mile for health equity collaboration and co-design.

Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for