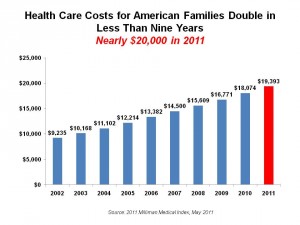

Health care costs have doubled in less than nine years for the typical American family of four covered by a preferred provider health plan (PPO). In 2011, that health cost is nearly $20,000; in 2002, it was $9,235, as measured by the 2011 Milliman Medical Index (MMI).

Health care costs have doubled in less than nine years for the typical American family of four covered by a preferred provider health plan (PPO). In 2011, that health cost is nearly $20,000; in 2002, it was $9,235, as measured by the 2011 Milliman Medical Index (MMI).

To put this in context,

- The 2011 poverty level for a family of 4 in the 48 contiguous U.S. states is $22,350

- The car buyer could purchase a Mini-Cooper with $20,000

- The investor could invest $20K to yield $265,353 at a 9% return-on-investment.

The MMI increased 7.3% between 2010 and 2011, about the same percentage increase in health costs for the past four years based on Milliman‘s research.

Another contextual point: average salaries in the U.S. increased about 3% in the last year. Thus, U.S. workers are being asked to shoulder an increasing proportion of health costs as their incomes grow much more slowly. Health care costs eat an increasing share of household budgets.

The fastest-growing component of health care cost increases is in outpatient services: this is due to growing cost per unit of outpatient service, along with more expensive ambulatory services emerging in the health market. Hospital costs, the largest single health care cost component, grew second-fastest at 8.6%. Milliman points to inpatient cost growth as the largest single contributor to the 2011 increase in the MMI.

Pharmacy costs rose 8.0% with most of the change coming from higher average prices for drugs.

Employers who sponsor health plans are trying out a variety of strategies to tame cost increases while bolstering quality, including:

- Consumer-driven health plans featuring high deductibles, health savings accounts or health reimbursement accounts

- Value-based benefits, where sponsors reduce costs and co-payments for health services that are seen to be preventive and health-maintaining

- Medical homes and accountable care organizations.

Milliman calls the “elephant in the room” in 2011 health care reform, being “the number one most talked-about subject in health insurance today.” Milliman anticipates the MMI will be impacted by the following aspects of health reform:

– Changes in minimum coverage, such as the elimination of lifetime benefit limits and removal of preventive care copays,

– Rate scrutiny, where cost reduction could focus on reducing administrative expenses, renegotiating provider payment rates, and other impacts.

– Individual mandate and expanding Medicaid, with the potential impact of new cost-shifting tactics where providers look to preserve compensation levels.

– Health insurance exchanges, that will drive transparency, commoditization, active purchasing (more aggressive negotiations by buyers), and expanded innovations to the non-exchange market (for health plan buyers who self-pay outside of the exchange).

The MMI is constructed based on nationwide average provider fee levels negotiated by insurance companies and PPOs, average PPO benefit levels under employer-sponsored health programs, and utilization levels representative of the average for commercially insured U.S. population (non-Medicare).

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The employee’s share of the total $19,393 health cost is nearly 40%, an all-time high. That employee-borne cost works out to $3,280 in employee out-of-pocket costs and $4,728 in premium payment contributions, for a total of $8,008 paid by employees. While employers are adopting mature and novel approaches to stemming the chronic 7% annual rise in health costs, employees’ wages stay relatively stagnant. At the same time, other household costs are increasing, from food and clothing (note the increase in commodity cotton prices) and, of course, energy — petrol for autos and home energy costs.

The nagging concern about health reform is what it can do to stem the spiral of cost increases from year to year. Every segment of health costs — inpatient, outpatient and physician, pharmacy and supplies — continues to grow. How can the U.S. deliver health care more efficiently, preserving quality and increasing access to the under- and uninsured?

The answer will be a complicated multi-stakeholder approach, and will take time to evolve:

- Extend care beyond the expensive hospital to the patient’s home and via mobile platforms where people “live, work, play and pray,” as Surgeon General Regina Benjamin likes to say.

- Provide incentives (‘nudges’) and useful and engaging support tools for people to better care for themselves when healthy – and engage in self-care when they are sick. Remote health monitoring and “infrastructure independent” care is the vision.

- Again, with an eye toward reducing expensive hospital stays and readmissions, focus on the high-cost conditions of chronic heart failure and other cardiac conditions, diabetes and obesity, and other conditions that cause people to be readmitted to the hospital through the revolving door of the (already over-demanded) emergency department.

- Pay primary care doctors more money to attract more professionals to the field and re-build the primary infrastructure that is critical to serving health citizens when they are well, and before they get sicker (and more expensive to treat). This will mean reallocating resources away from specialists — a battle that will heat up as Americans realize that, “It’s the prices, stupid” when it comes to our high-cost, low-performing health system. Click on the link to learn more about The Commonwealth Fund’s vision for a high performance health system.

This last point gets to the underlying uber-challenge of re-aligning financing in health care. The medical home concept, with value-based benefits that pay for what works and nudge both providers and patients toward healthy behaviors and collaborative, participatory health care, can be a vehicle to get the system moving in the right direction. This will take time — and health lobbyists representing the multi-stakeholders in the health value chain will work hard to conserve their own interests. But health citizens/people/consumers in the U.S. will be confronting higher costs in a system that still isn’t designed to deliver high performing health care outcomes.

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,

I am so grateful to Tom Lawry for asking me to pen the foreword for his book, Health Care Nation,  Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a

Thanks to Feedspot for naming this blog, Health Populi, as a