Once upon a time, patient satisfaction with visits to doctors’ offices used to be a function of bedside (exam room) manner, demeanor and responsiveness of the reception and insurance staff, and the age of magazines in the waiting room. Today, waiting time is a key factor, and social media is raising expectations around response time in health care.

Once upon a time, patient satisfaction with visits to doctors’ offices used to be a function of bedside (exam room) manner, demeanor and responsiveness of the reception and insurance staff, and the age of magazines in the waiting room. Today, waiting time is a key factor, and social media is raising expectations around response time in health care.

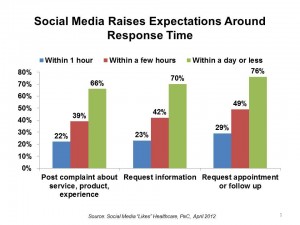

See the first chart, based on data from PwC’s survey, Social Media “Likes” Healthcare, published in late April 2012. The poll found that when U.S. adults use social media in healthcare, at least 4 in 10 people want complaints and information requests responded to within a few hours, and a majority want resolution within a day or less — especially for appointments and follow-ups.

This week at the American Telemedicine Association meeting, Dr. Jay Sanders, one of the pioneers in telemedicine, talked about the impending explosion of retail health, saying that, “healthcare providers have largely failed to… use established channels of distribution and low-cost technologies to serve patients better.” The new generation of retail health providers understands that time is money to patients, and that customer service that leverages technologies people use in everyday life are equally relevant and applicable for personal health management. More importantly, time is precious when making medical decisions of an acute nature.

For more on Dr. Sanders and other telehealth innovators, see my report, Right Here, Right Now: Ten Telehealth Pioneers Make It Work, from California HealthCare Foundation.

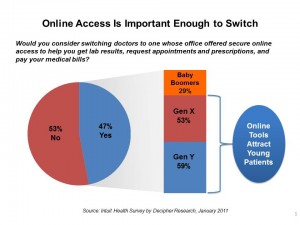

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The incumbent health care industry players should take this data point quite seriously. See the second chart, from Intuit’s survey of U.S. adults from 2011. It’s clear that about one-half of patient-health consumers would consider switching physicians if they don’t office electronic access to appointment scheduling, accessing lab results, and emailing patients, among other digital applications that people want. This piece of information should concentrate the collective mind of physicians, who may want to avoid providing patients with electronic access to schedules and personal health information. But when not doing so can lead to patients walking with their feet, and wallet, health providers should re-think their stance.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: The incumbent health care industry players should take this data point quite seriously. See the second chart, from Intuit’s survey of U.S. adults from 2011. It’s clear that about one-half of patient-health consumers would consider switching physicians if they don’t office electronic access to appointment scheduling, accessing lab results, and emailing patients, among other digital applications that people want. This piece of information should concentrate the collective mind of physicians, who may want to avoid providing patients with electronic access to schedules and personal health information. But when not doing so can lead to patients walking with their feet, and wallet, health providers should re-think their stance.

A discussion about consumers’ access to health information in Meaningful Use stage 2 is now brewing on the listserv for the Society for Participatory Medicine concerning the American Hospital Association’s view that hospitals should have 30 days to provide patients hospital discharge information — instead of within the proposed 3-day timeframe suggested in the original Meaningful Use criteria. We’re talking here about medication lists, discharge instructions to the home, lab test results, and other information crucial to making a safe transition to the home or step-down facility.

Patients expect at least as high a level of service from their health system they get from automobile repair shops, retailers, and banks. That the nation’s hospital association is bucking this consumer demand is short-sighted, unsafe for patients and their families, and counter to what technology-enabled customer service can deliver.

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on  I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,