The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) turns 75 today.

The NHS was the brainchild of Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan; he wrote in a statement to doctors and nurses in The Lancet on July 3, 1948, “My job is to give you all the facilities, resources, apparatus and help I can, and then to leave you alone as professional men and women to use your skill and judgement without hindrance.”

This week in The Lancet, the editors assert, “The founding principles of the NHS put into practice 75 years ago are at risk of being compromised.”

Like any 75th birthday, there is a lot to unpack — pain points and acute issues, stresses and a lot to reflect on during this long life of what has turned out to be one of the most beloved institutions in the United Kingdom.

In today’s Health Populi blog, I will discuss a current data-based snapshot of the NHS in 2023, adding context comparing the U.S. and other countries’ health system performance to appreciate the NHS in full based on its universal coverage ambition and health equity intentions.

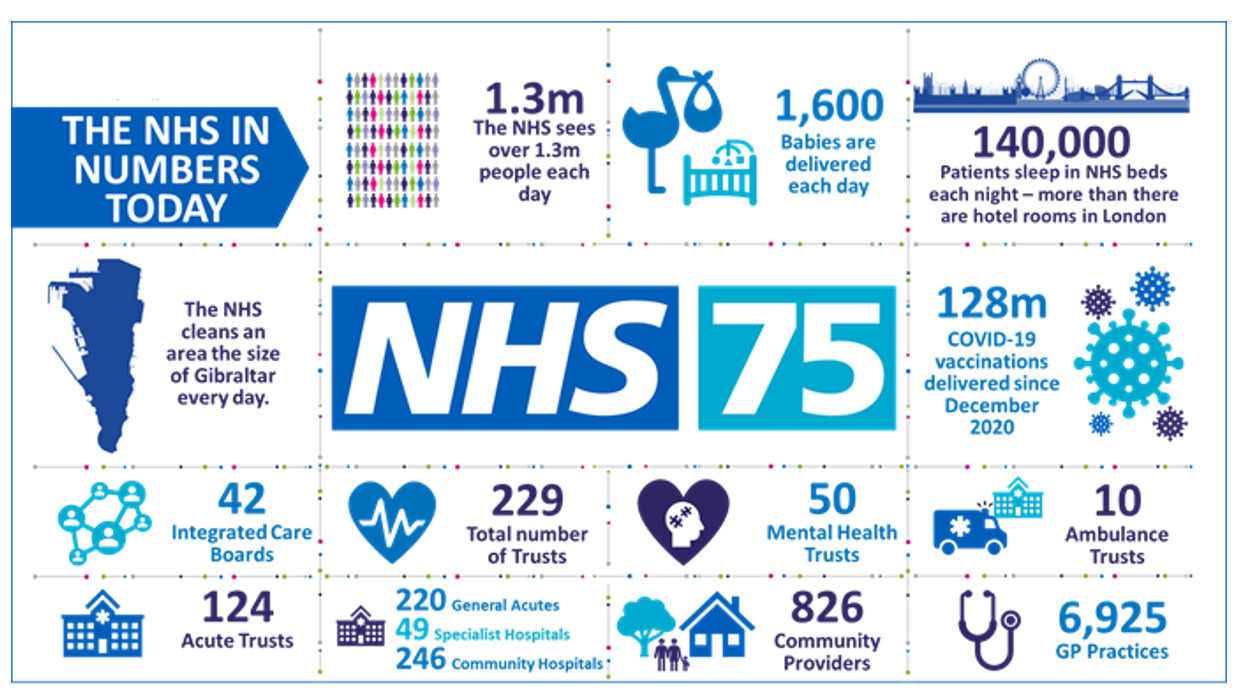

The NHS has over 1.3 million patient encounters every day, delivering about 1,600 babies daily and serving 140,000 inpatients in an NHS bed each night. The scale of the NHS makes it one of the biggest employers in the world with over 1.2 million full-time staff. Compare this to Walmart, with 2.3 million employees (globally), Amazon employing 1.6 million workers.

In comparison and health care context, UnitedHealth Group employs roughly 325,000 workers, CVS Health 290,000, and Walgreens Boots Alliance, about 287,000.

The King’s Fund published a report last month, asking the question, How does the NHS compare to the health care systems of other countries?

The answers to that query are, the report summarizes, that,

- The NHS is neither a leader nor laggard compared with 18 other countries’ health systems

- The UK has below-average health spending per capita compared with the other systems studied

- The NHS lags in capital investment with fewer key physical resources such as hospital beds and digital imaging scanners

- “The UK has strikingly low levels of key clinical staff, including doctors and nurses,” I quote directly from the report — a key issue with which the nation, health citizens and politics are now wrestling

- The NHS performs less well than peer health systems, the lagging part of the analysis, for specific measures o health status and outcomes, from life expectancy to cancer survival rates, and,

- UK health citizens are largely protected from the financial toxicity of health care costs compared with patients in the other nations’ health systems, although there is some evidence of self-rationing due to costs for some patients facing out-of-pocket spending for certain forms of medical care.

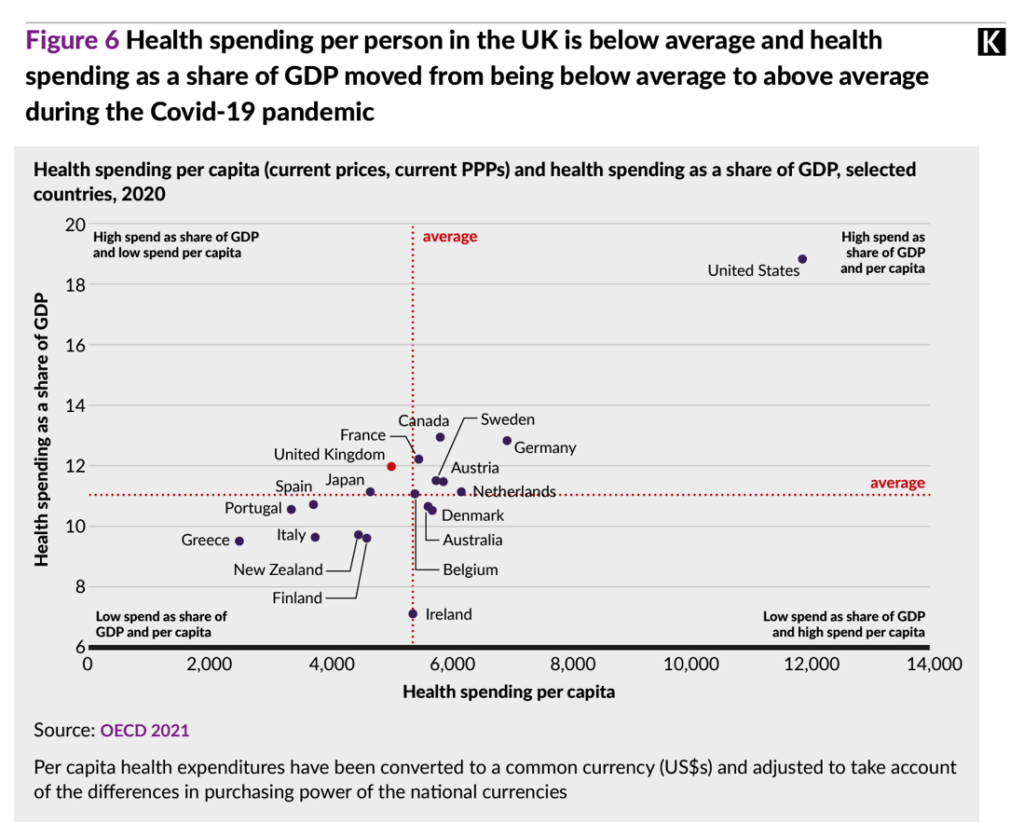

Figure 6 from the King’s Fund report arrays health spending per capita data points from the OECD’s 2021 national survey, finding the UK (the red dot on the graph) to the left of the red average line on the x-axis for per capita spending and just north of the average line of spending as a share of GDP on the y-axis.

Note the United States as dramatic outlier, to the north and east in the upper right quadrant with high spend of GDP share as well as high spend per capita, by far the highest on both metrics compared with all the OECD nations considered.

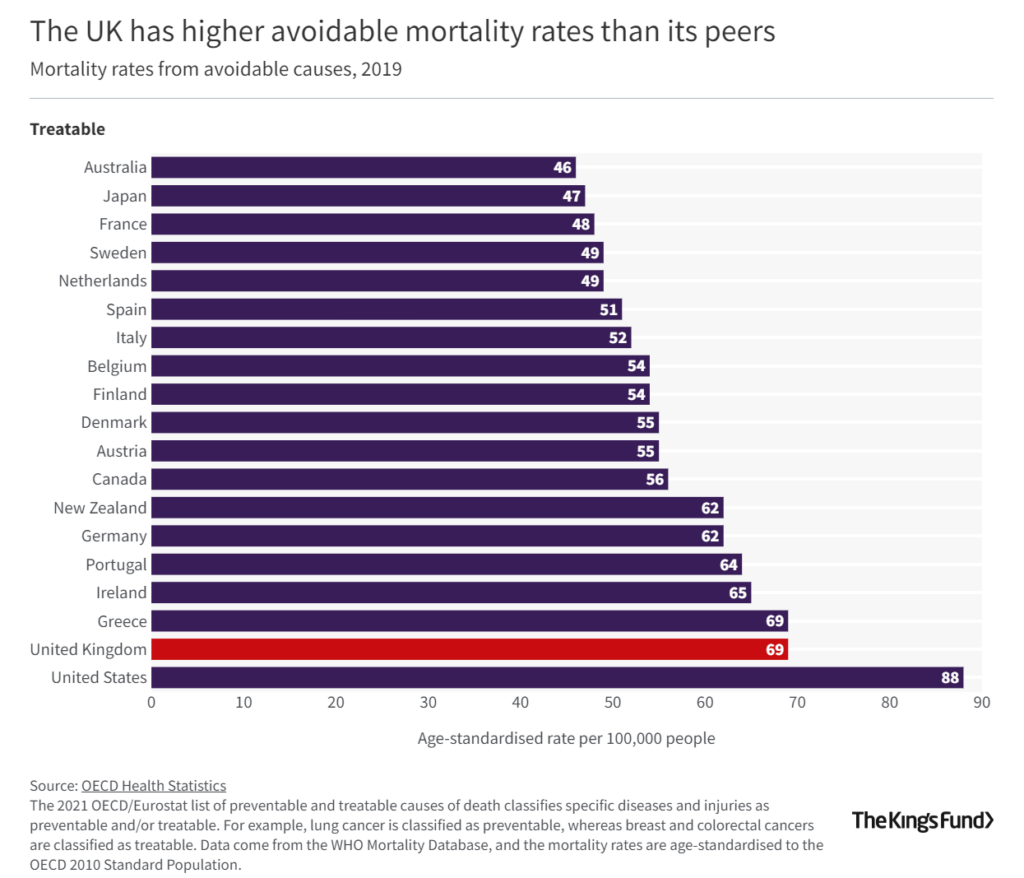

Outcomes produced by the NHS for the UK’s health citizen are also less optimal compared with most OECD nations, except for the U.S. which lands dead last in the league table of nations’ mortality rates from avoidable causes in 2019.

The U.S. rate was 88 per 100,000 people versus 69 for the UK and Greece, 65 for Ireland, and 64 for Portugal.

Avoiding mortality is most successful when you live in Australia, Japan, France, Sweden, the Netherlands, Spain, and Italy, the bar chart illustrates.

Why is this the case? In part, these health outcomes can be significantly influenced by factors both within the health care system as well as the environment, social care, and other drivers of health (those social determinants of health we cover here in Health Populi as core to our wheelhouse and advisory work).

As The Lancet stated on July 1, 2023, “Strengthening of primary and community care, public health, and broader preventive measures beyond the health sector” will be an important remedy to assure NHS survival and effectiveness. That, along with bolstering current and future health care workers — doctors and nurses, and allied health professionals — through fair remuneration/pay, improving the workplace environment, and authentically supporting the health care workforce in deed and not just in word, The Lancet explains.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: I spent an early part of my career living in London and working with the NHS through my consulting job with Touch Ross (now Deloitte). At the time, Prime Minister Thatcher was advocating various privatization strategies from the laundry and dietary functions to clinical care, but the beloved nature and UK health citizens’ affection for the health service kept most of those proposals from being adopted and implemented.

Fast forward 30 years, and health systems around the world are all facing decisions that will require trade-offs sooner or later both within the traditional health/care ecosystem — between hospitals and outpatient sites of care, from inpatient to ambulatory care to the community and patient’s home leverage digital health and telehealth technologies. These conversations are happening throughout the OECD community, country by country.

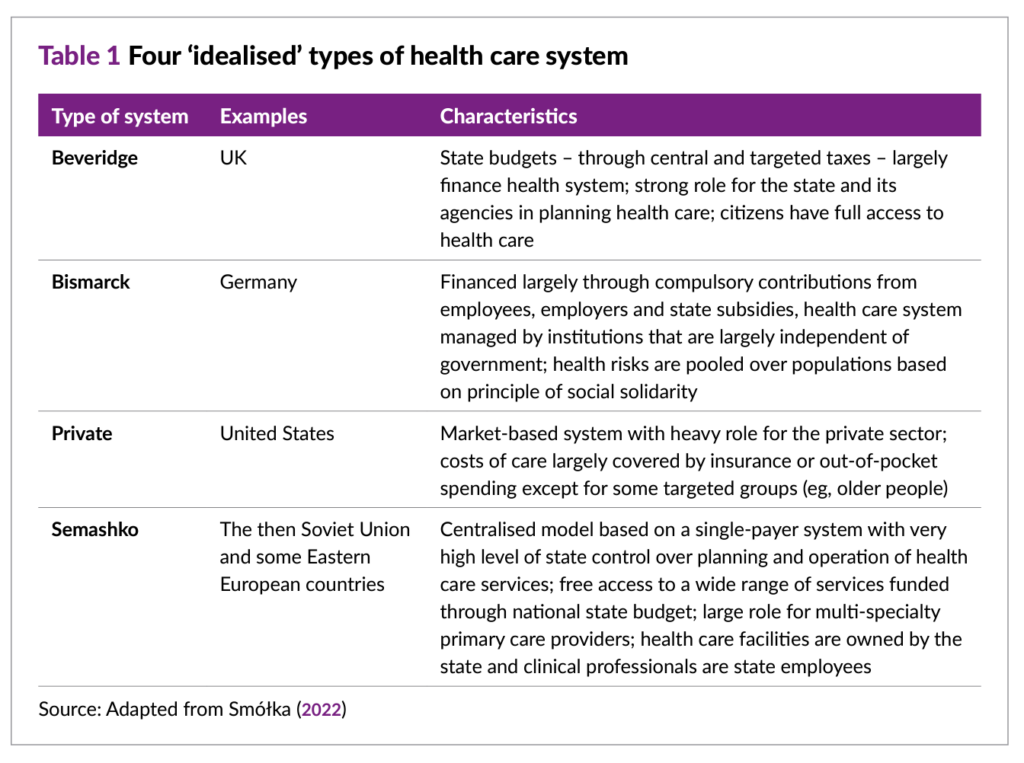

The Table 1 shown here from The King’s Fund report lays out a summary of the four idealized types of health care systems — from Beveridge and the UK model of single payer, to Bismarck’s vision deployed in Germany (a mix of public/private financing with a strong social safety net and ethos), the US private system, and centralized models largely found in parts of Eastern Europe.

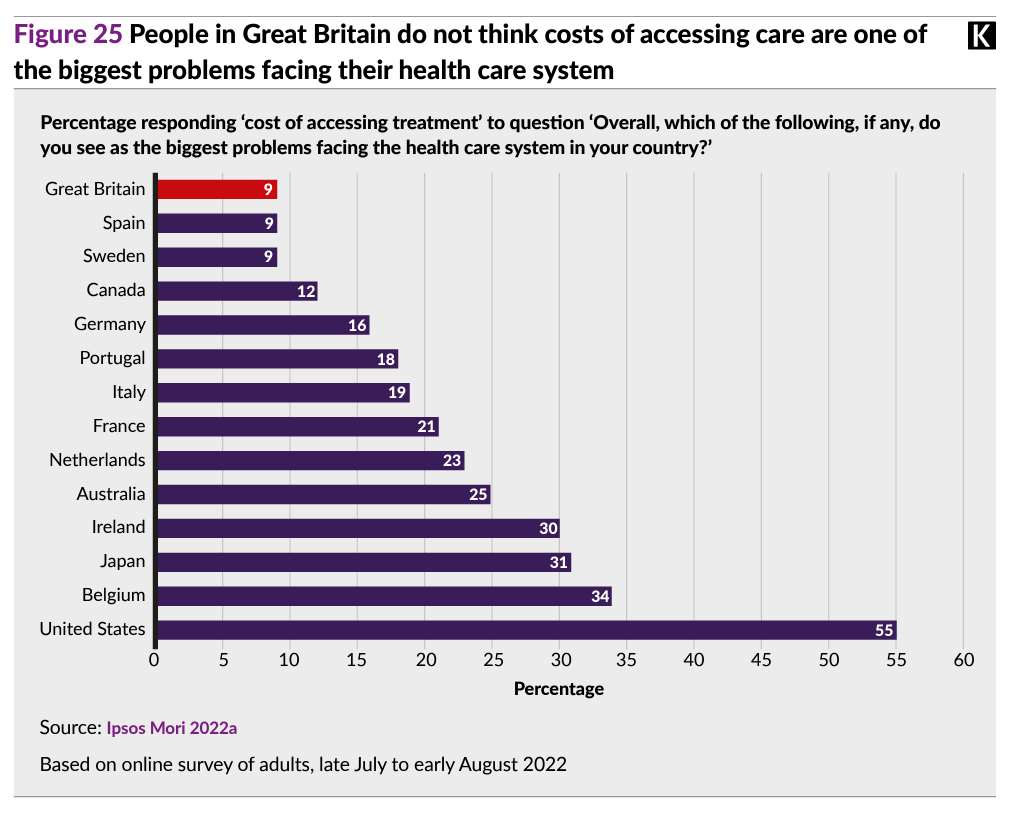

Health citizens in Great Britain are the least-likely among OECD peers to cite the cost of accessing health care treatment as the biggest problem facing health care in the UK. In the U.S., that’s the prime problem cited by 55% of Americans one year ago in an Ipsos survey,

In the UK, the NHS is primarily funded through taxation of the people, ensuring and insuring every health citizen’s health care access. Today, access to that care has more waiting lists as well as poorer outcomes than peer systems, and a very present and future crisis among the supply of front-line clinicians — doctors and nurses.

This is a question of money and remuneration, in the eyes of physicians and nurses, as well as what the taxpayer can expect from a long-loved system letting public expectations down.

The NHS has an opportunity to renew a vision the public holds — or has held dear — this King’s Fund blog explains.

But that NHS-love-equity has eroded since the start of the pandemic: there has been a precipitous fall in public dissatisfaction with the NHS riding from 25% in 2020 to 41% in 2021.

Still, most people in the UK still believe in three key principles on which the NHS was conceived and implemented — these are that,

- The NHS should be free of charge when you need it

- The NHS should be available to everyone

- The NHS should primarily be funded through taxes.

Across political party, whether a health citizen identified with Labour or Conservative, The King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust found that most folks agreed with the three underlying principles — the exception, at the margin, being that 48% (just under one-half) of people identifying as Conservative thought the NHS should be primarily funded by taxes.

Pondering the 75-year birthday of the NHS gives one pause to ask, “where is the love for the U.S. health care system?” We cast our eyes back across the Atlantic to the U.S. side of the health policy pond, noting public dissatisfaction among U.S. health citizens is also high based on, say, a recent AP-NORC poll conducted in September 2022.

Like our health citizen cousins in the UK, more U.S. health citizens will be asking tough questions about what they hold dear about health care in America, how much they pay for that care, and what they get in return. We can learn a lot about what matters in health and health care by listening to our fellow health citizens — both those who are patients in our home countries, and those dealing with health care in other nations and health systems.

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for