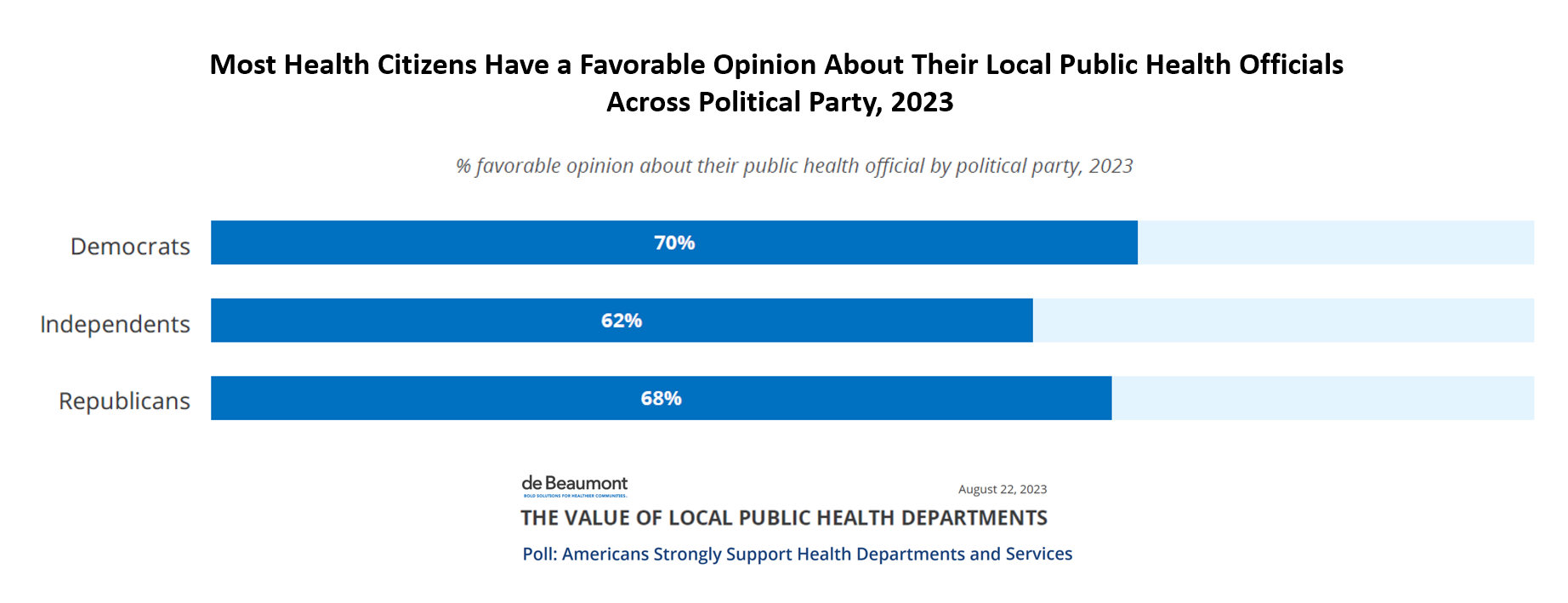

Appreciation for public health in America tends to be a local-love thing, according to research from the de Beaumont Foundation.

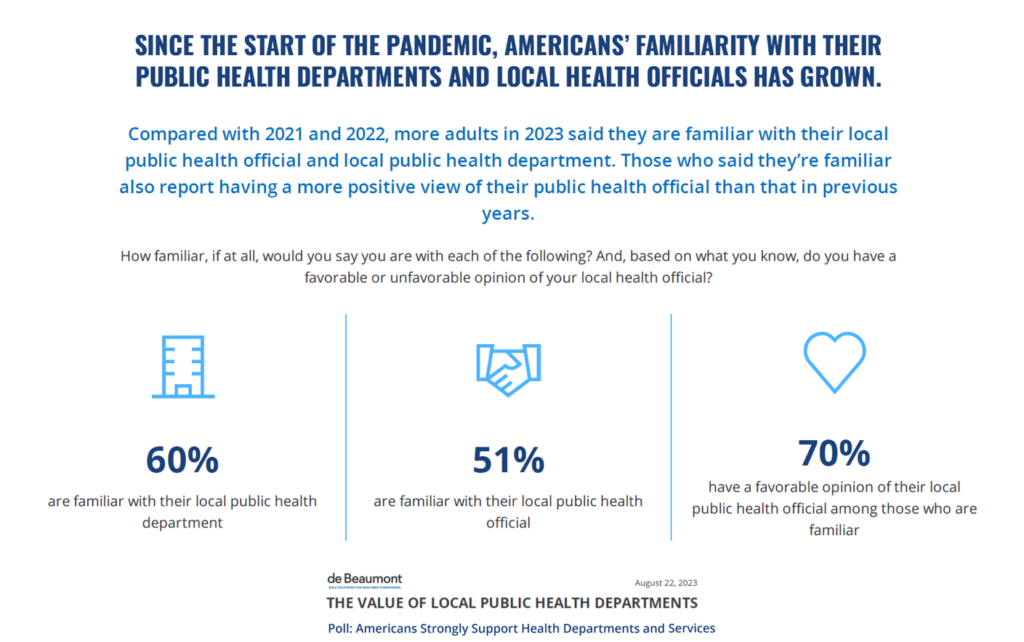

The COVID-19 pandemic raised health citizens’ awareness of the role and importance of public health — and for 7 in 10 people in the U.S., inspired a favorable opinion of their local public health officials, de Beaumont found.

the Foundation’s President and CEO, Briant Castrucci, DrPH, observed,

“The shared pandemic experience seems to have driven deeper familiarity with and support of public health departments and officials, along with a stronger understanding of the important role of public health in keeping families well.”

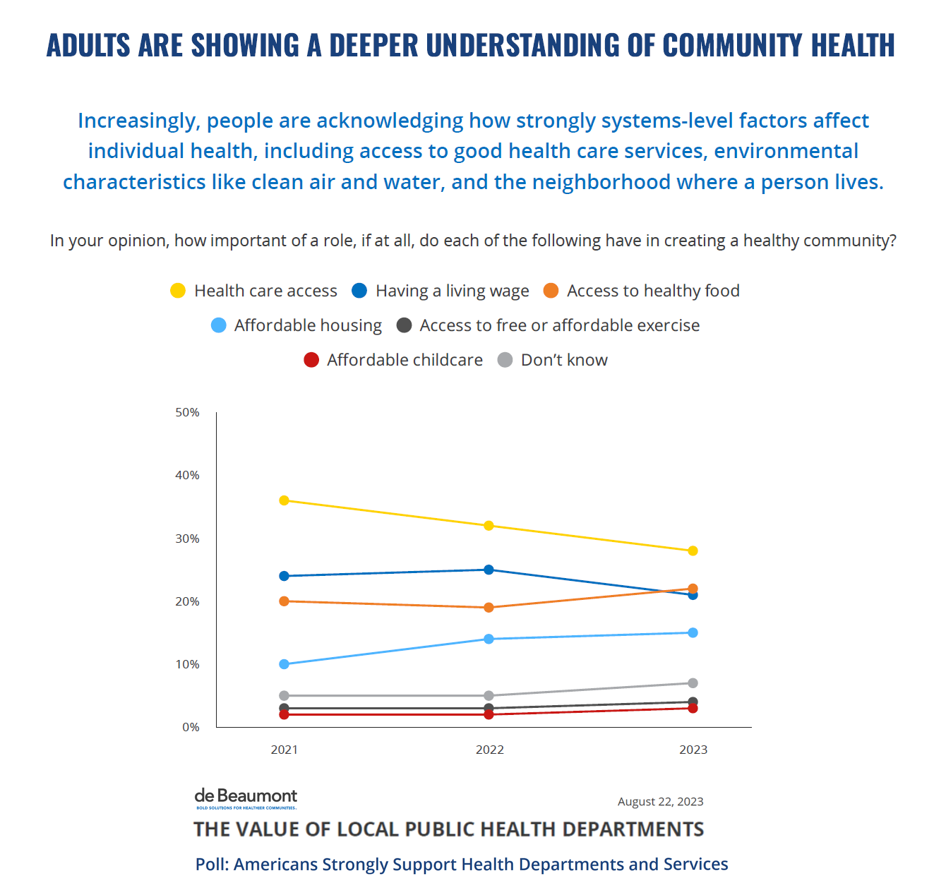

A big part of learning about public health and its local value was peoples’ growing understanding of the social determinants, or drivers, of health that shape medical outcomes and residents’ well-being in their communities.

t\he second line chart shown here from the Foundation’s report arrays various SDoH factors, such as health care access, housing, and access to healthy food, and how health citizens felt the factor impacted their community’s health.

From 2021, we note people were placing less emphasis on access to health care and growing appreciation for the roles of health food and affordable housing.

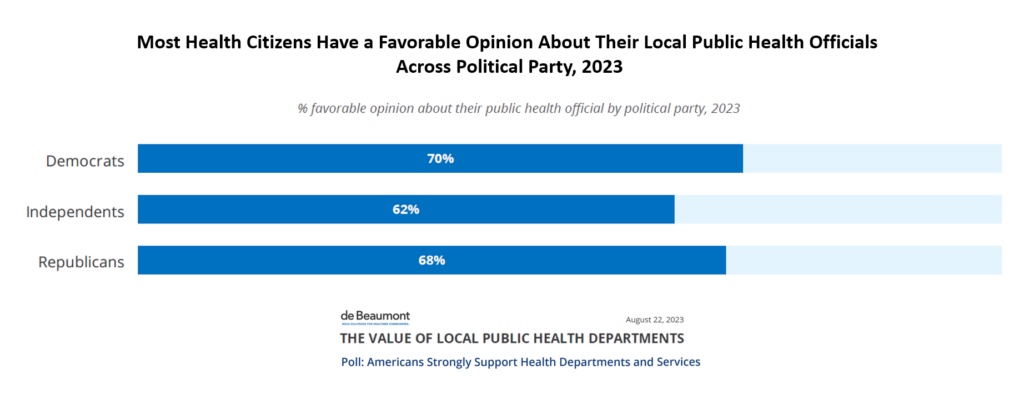

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Trust is a key pillar for people’s personal health engagement, and it is for their commitment to public health as well.

In the current political and social schism facing America and her residents, it’s mighty encouraging to cite this data point — that across political party IDs, most health citizens have favorite opinions about their local public health officials. That’s 70% of Democrats, 62% of Independents, and 68% of Republicans.

This is a solid base to build on at the local level, channeling the great Thomas “Tip” O’Neill’s mantra that “All politics is/are local.”

Tip was the former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, reaching a kind of political legendary status for his ability to govern, strike compromises across his political aisle (Democrat), and mentor many politicians who serve on Capitol Hill today. While he didn’t originate the “local” phrase, he is deeply associated with the concept having titled one of his books with it.

Tip’s point here had to do with the local skills a politician could leverage to win a primary election that, then, resulted in their getting their safe seat in Congress. Those local skills included everything from kissing babies at county fairs, shaking hands door-to-door, attending local business meetings with the Kiwanis and other community organizations, and getting dollars earmarked for local projects (which Tip was legendary at securing).

To be clear, though, in today’s social-media, bubble-populated environment, all politics clearly are not all local.

Nor is public health. What happened in Wuhan didn’t stay in Wuhan. We didn’t need to learn this from the coronavirus, as once upon a time the Miami area tried to cordon off certain ZIP codes and census tracts with the aim of containing the Zika virus.

That didn’t work.

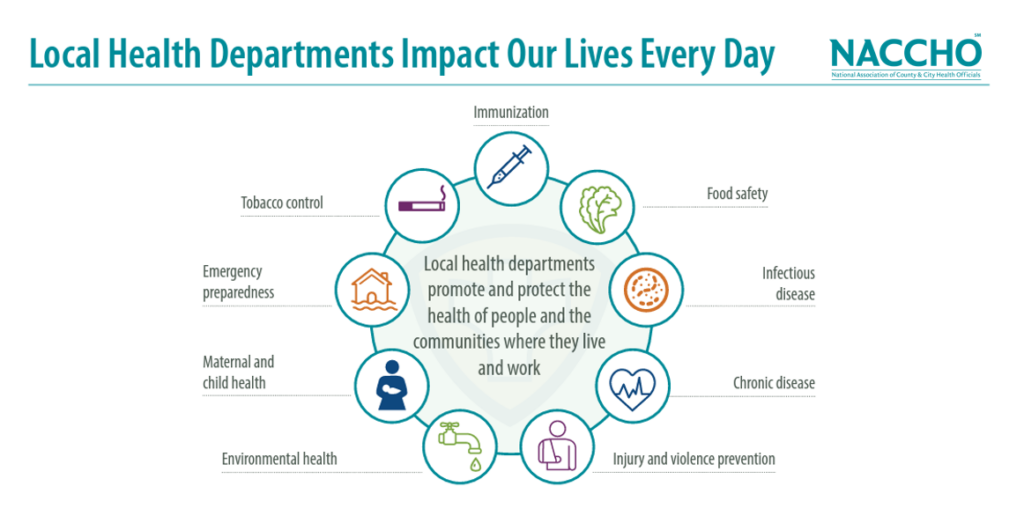

For public health, there is much to do locally, the NACCHO inventories for us in the graphic here.

In just the past few days, public health departments around the U.S. have had to deal with the impacts of weather disasters, environmental hazards, maternal and child health mortality, gun violence and emergency preparedness, food safety issues, immunization challenges and misinformation, among other real-time tasks.

That’s locally; nationally, these missions require macro-plans, budgets, and authority.

We face an opportunity to take the de Beaumont findings, see and act on that half-full glass: that perhaps we can build up confidence in public health through trusted local departments, re-build trust in science facts, and work very hard to prevent or stem the worst coming from the next pandemic.

Because we know, with certainty, there will be another pandemic for which, in the current state of U.S. public health, we are surely unprepared.

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast

Grateful to Gregg Malkary for inviting me to join his podcast  This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're

This conversation with Lynn Hanessian, chief strategist at Edelman, rings truer in today's context than on the day we recorded it. We're