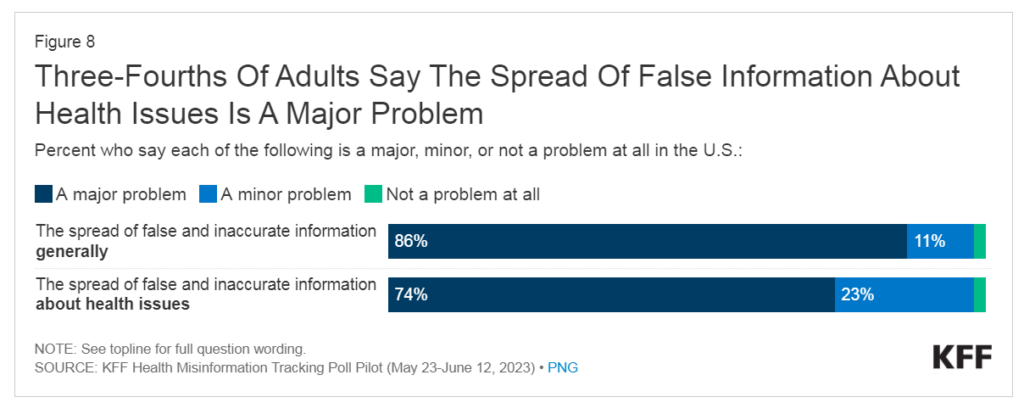

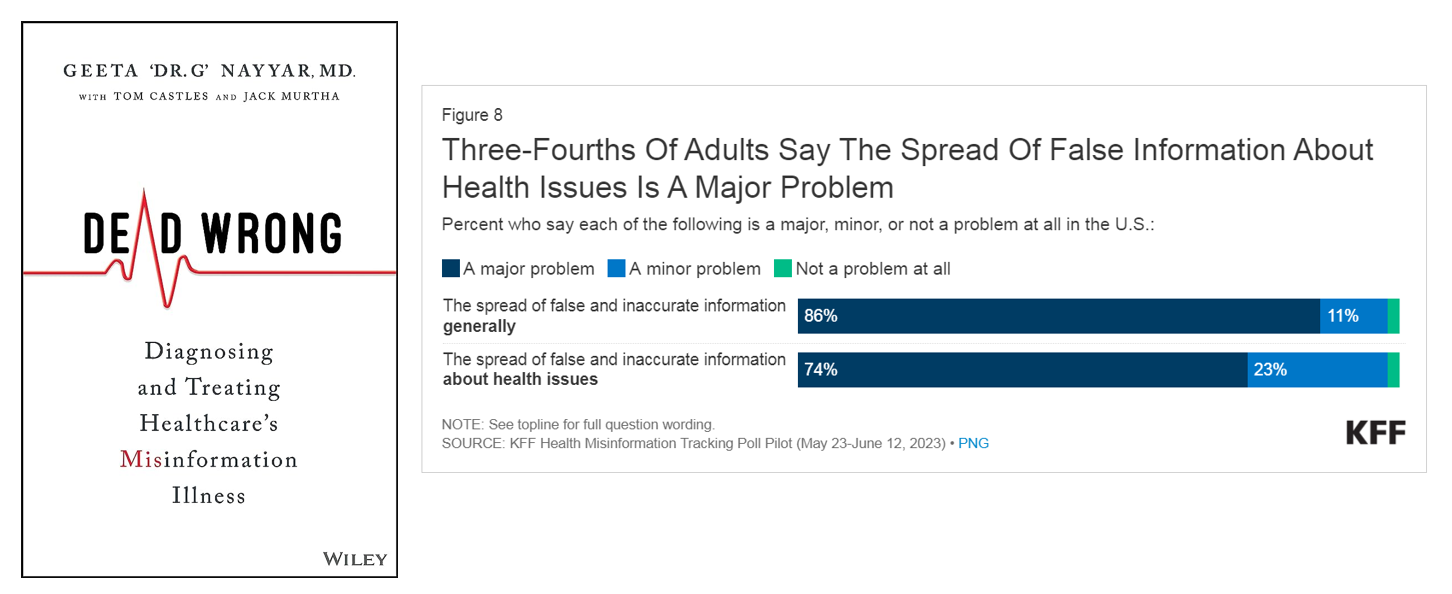

Three in four U.S. health citizens say the spread of false information about health issues is a major problem, found in Kaiser Family Foundation’s Health Misinformation Tracking Poll Pilot published earlier this month.

KFF’s press release on the study summarized the top-line with, “Most Americans Encounter Health Misinformation, and Most Aren’t Sure Whether It’s True or False.”

Explaining the implications of the broad reach of health misinformation in the U.S., Dr. Geeta Nayyar has written the book Dead Wrong: Diagnosing and Treating Healthcare’s Misinformation Illness, due out on October 17th and available now for pre-purchase wherever you love to buy your books. Geeta took on the persona of “Dr. G” through her public health-informed broadcasts in the Miami media market during the pandemic. For the book, she collaborated with two communications veterans, Tom Castles and Jack Murtha, bolstering the book’s wisdom and plotline.

The phenomenon of medical mis-information accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, normalizing weird anti-science and culminating in the rejection among many U.S. health citizens of the vaccine fast-tracked to address the worst effects of the coronavirus. “Misinformation” has taken on many names: infodemic (coined by the World Health Organization in August 2020), fake news, conspiracy theories, and malinformation among the monikers. A team of global physicians and researchers conducted a meta-analysis to define misinformation and related terms in health-related literature, published earlier this month in the Journal of Medical Internet Research.

As Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of WHO, said of misinformation during the COVID-19 era,

“We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic, [that] spreads faster and more easily than this virus.”

And to be sure, as Dr. G demonstrates in Dead Wrong the results of that easy-to-spread malinformation can be death and disability.

Let’s first learn from the Kaiser Family Foundation on the contours of the medical misinformation challenge in the U.S.

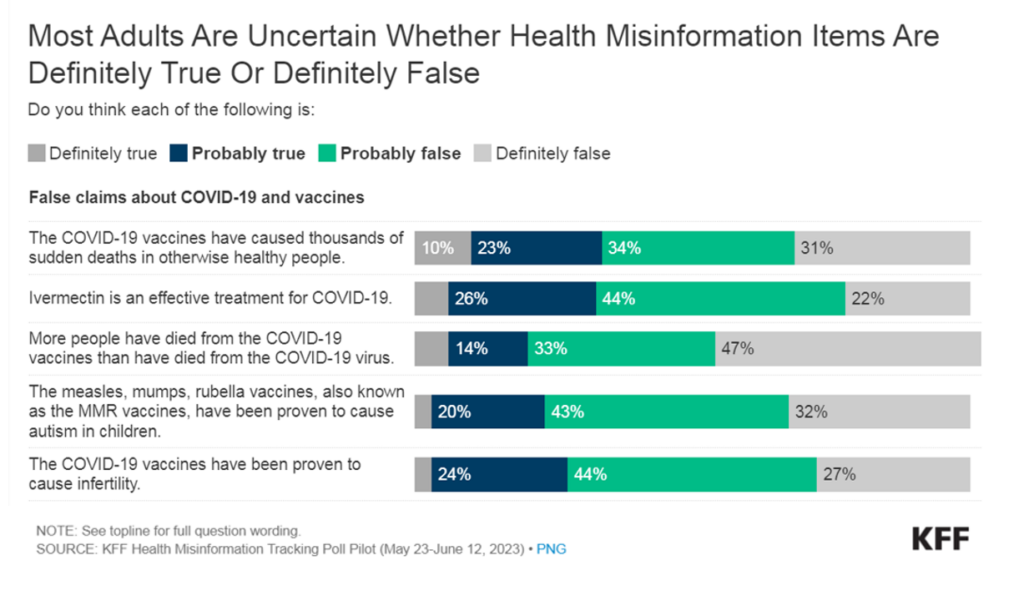

KFF fielded the study in May and June 2023, finding that most U.S. adults had heard a variety of health information stories, some shown here in a bar graph from the report. Two in three people in the U.S. had heard about COVID-19 vaccines causing thousands of sudden deaths in otherwise healthy people, with one-third of consumers believing this was true.

Nearly 50% of people had also heard of Ivermectin being an effective treatment for the coronavirus, with 31% of folks believing this to be true.

And 41% of U.S. adults had heard that more people had died from the COVID-19 vaccines than from the COVID-19 virus, with 20% of people believing that to be true.

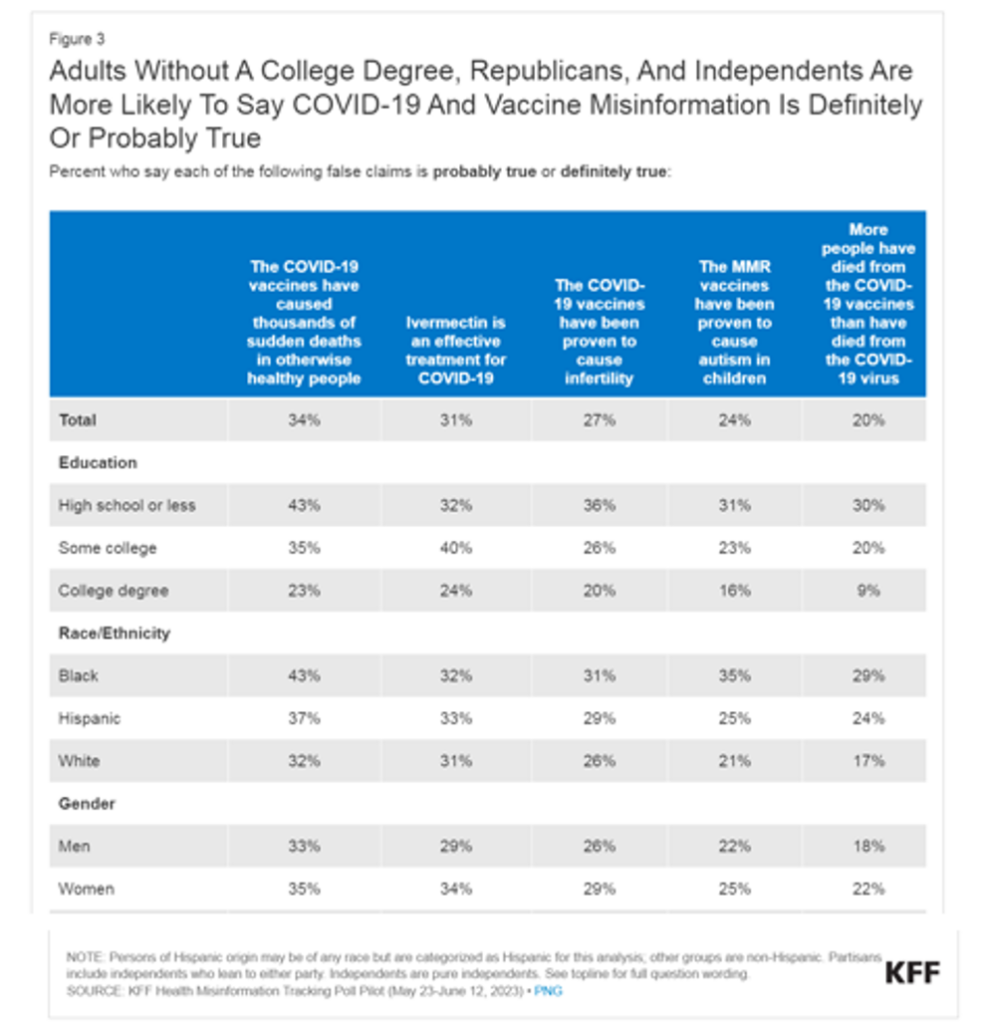

Peoples’ belief in vaccine misinformation is related to their level of education and race and ethnicity, along with one’s political party affiliation, age, and community type (whether a rural resident, or living in urban or suburban areas).

KFF found that people without a college degree, Republicans and Independents, and rural residents were more likely to say that COVID-19 and vaccine misinformation were true.

The choice of media to consume for news and health information also seemed to shape Americans’ views on medical misinformation, KFF found. People in the U.S. who watched Newsmax, OANN, and Fox News were more likely to have heard and to believe at least one issue of COVID-19 misinformation.

With this state-of-the-state-of-the-infodemic in mind, we turn to Dead Wrong. The chapter titles immediately tell us about the ride we’re about to take starting with “A Fatal Misconception” followed by “A Pandemic of Lies” and “Our Tainted History” coupled with “New Traumas, Old Wounds.”

By the end of the book, we re-live the shock to the healthcare system that was COVID-19, what we could learn about trust and empathy (or lack thereof), and finally the Holy Grail pursuit for all in the health/care ecosystem: to Do No Harm. And from the initial sentence of the book, that “The truth is on life support” to doing no harm, we hear numerous stories about patients, people, families, caregivers, and providers who lived with, and sometimes died due to, the lack of truth.

Dr. G explains the rationale for writing Dead Wrong right up-front: “I decided to write this book because I wanted to help healthcare leaders see misinformation’s real-world repercussions for the nation and the industry. I also hoped to serve up promising solutions. I set out to help people see what was happening because I need readers to hear and feel the call to action.”

Among many eye-opening lessons for me in Dead Wrong came through a conversation Dr. G had with Dr. Megan Ranney, who was one of several physician voices delivering science fact during the coronavirus pandemic on national news channels.

“Misinformation, like a real virus, needs a conducive environment and hosts to spread. Our modern society provided both, Megan said. Our world was a perfect breeding ground for three reasons,” Dr. G writes.

This breeding ground is a fertile landscape for a medical infodemic ecosystem due to three intersecting factors:

- Misinformation is profitable. Dr. Ranney noted, “It sells things. It gets people to buy stuff they don’t need—useless supplements and ridiculous tests.”

- Misinformation provides opportunities for “bad actors to punch above their weight and speed up societal breakdown,” with those “bad actors” including people in politics, media and popular culture, and to be sure, medicine.

- “Misinformation thrives in the digital spaces society increasingly relies upon,” drawing on what Dr. Ranney coined was “the social dysfunction of the pandemic.” As more workers worked remotely and media bubbles consolidated on “screens,” there was greater probability people were exposed to viral misinformation campaigns that aligned with personal interests and values. [Did someone say “algorithm?”]

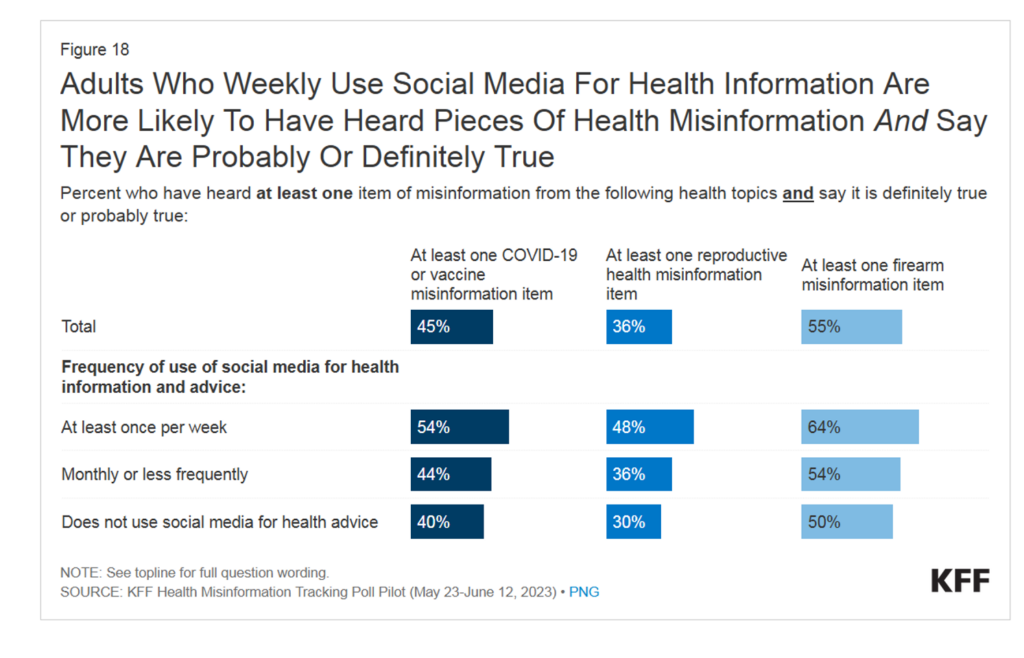

This realization couples with KFF’s research – here is Figure 18 from the report on adults who used social media weekly for health information and who were more likely to have heard pieces of health misinformation and say “they are probably or definitely true.”

As Geeta’s mother advised her when as a student Geeta was dealing with a knotty physics problem, “we just need to find a way to get through this mess.”

And so armed with real-life stories and heartbreaks and data, we learn from some very special clinicians, researchers, health administrators, communicators and technology innovators ways to hack through the infodemic challenge. The experiences of Dr. Adrienne Boissy, Dr. Michael Dowling, Dr. Peter Hotez, Dr. Larry Brilliant, Dr. Toby Cosgrove, Dr. Paul Offit, Bruce Turkel, and Abner Mason, among many others Geeta interviewed in the course of researching Dead Wrong, give us hope and practical advice for this moment: channeling empathy, science fact through engaging communications, interoperable health records and data analytics, and health equity-by-design, among other insights Dead Wrong shares from experts working on the front lines of the pandemic.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy has taken on the challenge of medical misinformation, calling it a serious threat to public health. “It can cause confusion, mistrust, harm people’s health, and undermine public health efforts,” he asserted, releasing a Community Toolkit for Addressing Health Misinformation to help guide people toward practical tactics to address the infodemic — especially that spread through social media and via other online channels.

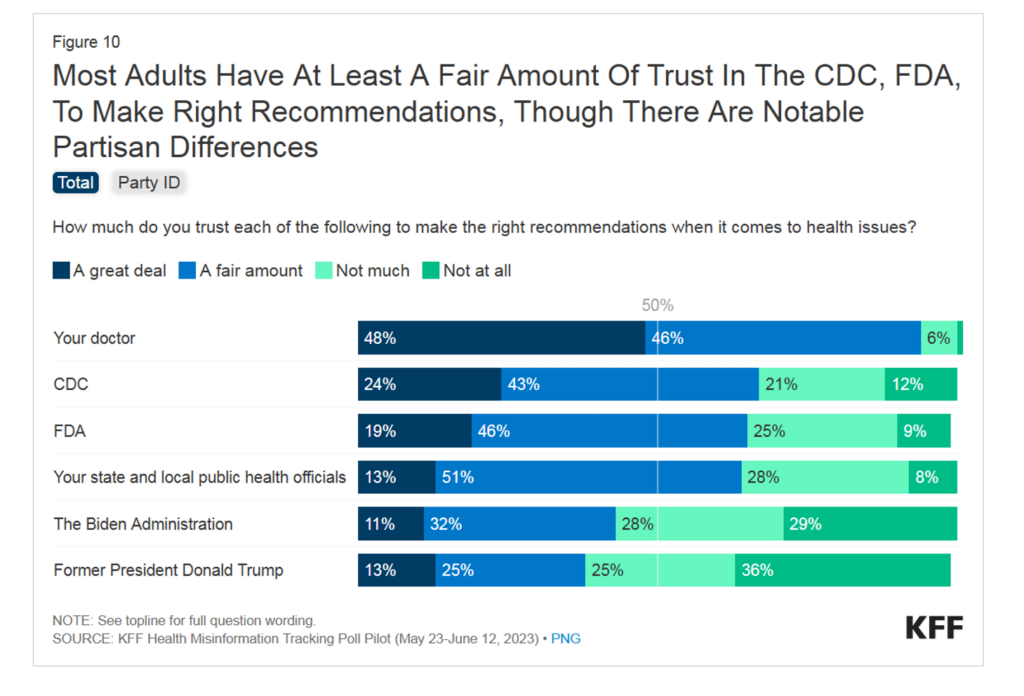

We can and must be hopeful and up to the challenge of reversing the medical infodemic. This last chart from the KFF research tells us who U.S. health citizens trust most to make good health recommendations — led first by our personal doctors, following by the CDC, the FDA, and state and local public health officials (which I wrote about this week in Health Populi).

“Most people aren’t true believers in the lies or the facts about health issues; they are in a muddled middle,” KFF President and CEO Drew Altman said in his reflection on the KFF misinformation pilot research. “The public’s uncertainty leaves them vulnerable to misinformation but is also the opportunity to combat it.”

Along with a long tail of mental and behavioral health issues and negative financial impacts that have affected many people in the COVID-19 pandemic era, we add another side effect that’s been toxic: the infodemic.

For one more healthy dose of Dr. G goodness, check out this interview she had with the American Medical Association’s Todd Unger on the topic of course-correcting medical misinformation.

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on

Thank you, Trey Rawles of @Optum, for including me on  I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming

I was invited to be a Judge for the upcoming  For the past 15 years,

For the past 15 years,