In the current paradigm of Too Big To Fail, are cancer drugs and care Too Costly To Consume?

In the current paradigm of Too Big To Fail, are cancer drugs and care Too Costly To Consume?

A plethora of evidence says that, for a growing number of health citizens, the answer is “yes.”

First, think about the scope of the cancer challenge in the U.S. The March 17 2010 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association focused on cancer: prevalence, treatment, and cost. Elkin and Bach’s article talks about addressing cancer’s next frontier – not treatment innovation, but costs. In their article on caring for patients with cancer, Pasche et. al. write, “With the current lifetime probability of being diagnosed with invasive cancer estimated at 37% for women and 44% for men, have had or will have a family member who has been affected with or has succumbed to this complex and dreaded disease.” So cancer is All of Us.

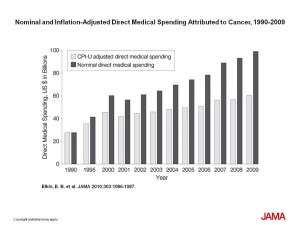

The macreconomics of cancer is that, top-line, the cost of cancer care, adjusted for inflation, reached $90 billion in 2008. The microeconomics is that a cancer treatment can cost a patient (and her family) $100,000 for a year’s treatment.

The Washington Post and Kaiser Health News collaborated on a story on April 27 2010 which demonstrates the impact of cancer economics on the family. It’s a tale of denied access: even for people with health insurance, high cost specialty drugs are often denied either explicitly or implicitly through high coinsurance amounts. The reporters found that reimbursement can cover invasive, hard-to-tolerate IV chemo, but less-invasive oral chemo is seen as part of the (carved-out) prescription drug plan which doesn’t cover full cost of these meds. These medications are usually categorized in the expensive (fourth) tier of drug plans. “Some plans cap drug benefits at $5,000 annually, which can amount to less than a month’s supply of chemotherapy pills,” WashPo/KHN say.

If current reimbursement schemes continue, the forecast is pretty dire: 25% of 400 chemotherapy drugs in the pipeline are oral meds. Thus, as we’ve seen with health plans having to cover mental health care under “parity” laws, some legislators and doctors are calling for “chemo parity” to harmonize reimbursement for cancer drugs, whatever their mode of delivery (i.e., injectable vs. oral vs. transdermal).

And this thread of conversation leads to the third cancer story this week that provides the Poster Child example of real-world denial: WellPoint’s alleged dropping coveragefor patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Secretary of HHS Kathleen Sebelius has stated that health reform under The Affordable Care Act specifically prohibits insurance companies from rescinding policies.

According to a Reuters report, WellPoint, the largest U.S. health insurer by enrollment, has been using a computer algorithm that targeted newly-diagnosed breast cancer patients. Other conditions may have also been involved, according to Reuters.

Capping this story of cancer this week is a new study by Dinan et. al. out of Duke University published in the April 28 2010 issue of JAMA that finds that the costs of medical imaging among cancer patients on Medicare increased twice as fast as overall costs for cancer care. These scans including CAT, MRI and PET — the most expensive digital imaging study type available — about six times the cost of a CT scan. PET volumes increased the most quickly during the study period. The researchers point out that more scans do not lead to better outcomes or therapy.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: Costs are a barrier to first-class care in America’s third-class health insurance system.

The current news items discussed in this post paint the economic landscape of cancer in 2010. So many questions arise: how do we pay for world-class cancer care in the U.S.? How do we incentivize innovation for cancer? How can we re-imagine a new and improved War on Cancer beyond the 1971 vision of Richard Nixon, a vision that leverages what we’ve already been learning about personalized medicine, coupled with using health information technology and tools that patients want to embrace as well as providers and researchers?

There remains a Big Question beyond The Affordable Care Act’s reach: that is, how to pay for first-world cancer care for all Americans – without discrimination, broadly writ? Without concern about payer type, whether employer (large or small), Veterans Administration, Medicare, or Medicaid. Without ruling out certain kinds of cancer, like breast or prostate or brain. Without variation based on geographic locale, whether West Virginia or New York or Arizona.

For now, under the status quo of reimbursement in the U.S., cancer care seems Too Costly To Consume.

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider

I love sharing perspectives on what's shaping the future of health care, and appreciate the opportunity to be collaborating once again with Duke Corporate Education and a global client on 6th May. We'll be addressing some key pillars to consider in scenario planning such as growing consumerism in health care, technology (from AI to telehealth), climate change, and trust -- the key enabler for health engagement or dis-engagement and mis-information. I'm grateful to be affiliated with the corporate education provider  Thank you FeedSpot for

Thank you FeedSpot for